Volume 3, No. 5: A Little Ancestral Tenderness, Please + Creamy Mushroom Quiche

Greetings, book and treat people! January is one of my two favorite months, but this was a rough one, so I can’t say I’m sad to see it go. I have not been writing fiction every morning like I told myself I would, but I have been taking a few minutes every day to watch the light, and that’s been a small, good something. I hope you’ve found a few small, good somethings, too.

Last time I shared a stack of hefty nonfiction books I'm planning to read in 2023, and asked if anyone was interested in reading and discussing them with me. I am thrilled to announce that there is now a discord! It’s informal but wonderful. We’re reading Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments in February, and it’s incredible. It’s not too late to join and read this book (or any of the others) in community! Email me if you’re interested and I’ll send you the link.

Today’s newsletter is an extension/continuation of the essay I wrote last week about queer literary ancestry. I cannot stop thinking about this, so it will likely not be the last time you hear about it from me. You can check out the essay, “What Do We Owe the Dead?” here.

I have been reading a lot of 20th century queer lit this year. It’s hard to explain how much these books mean to me. Reading them has cracked something wide open inside me. I have a lot of tangled feelings about them, because reading queer texts from 50 or 100 years ago is not simple. It shouldn’t be. That’s part of what makes it good. But along with all my tangled feelings, I have so much tenderness for these books and their authors. Tenderness for their mistakes and imperfections, for their clarity and mess, for the spaces between them and me, for their mysteries and their resonance, their cracks and their wisdom. I just want us all to listen to these voices, these songs, with soft and open hearts. I just want us to let them breathe. Tenderness, I think, is one way to look at something truly. It isn’t about ignoring what is hard. It’s about honoring where the hard and broken pieces come from.

The Books

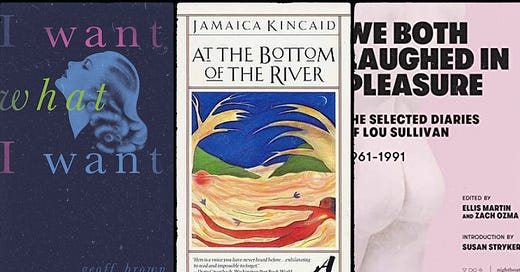

I Want What I Want by Geoff Brown (Fiction, 1966)

This is tough book, and I can understand not wanting to read it right now (or ever), so I’ll start with the content warnings: transphobia, deadnaming and misgendering, domestic violence, homophobia, misogyny, suicide.

This remarkable book from 1966 is about a 21-year-old trans woman, Wendy, trying to make a life for herself in the city of Hull, in Yorkshire. After her family institutionalizes her for being trans, she returns briefly to her father’s fish-and-chip shop, before finally getting herself free. She finds a small apartment and begins living as herself. There are two important things to know about this book. One: it is full of queer suffering, and it does not have a happy ending. Two: Wendy is a complicated, nuanced human being—she is not a trope, a stereotype, or a villain. She is far from perfect, but she has agency.

While Wendy deals with seemingly endless transphobia, this is really a book about being isolated. She has no one she can be herself with, no one she can trust. Imagine how much excruciating effort it takes to know and name yourself in a world where no one else sees you. And so—she is deeply homophobic and sexist. She buys into every stereotype about the gender binary. She’s obsessed with having the right clothes and looking like a proper lady. I don’t think it’s because she is “of her time.” Yes, there are facets of her identity—her whiteness, her class status (she doesn’t have much money), her geographical location—that affect how she moves through the world. But there were queer and trans people in 1966 who were fighting back against so much of what Wendy buys into. It’s hard to do better without anyone to help you. It’s learn to learn if there’s no one to learn from. Of course Wendy wants to be a “perfect” woman, of course she thinks she can’t be happy until she is one. There’s no one to tell her there might be another way. Isolation is a form of violence.

Given how isolated and alone she is, her fierce advocacy for herself is really something. At one point she writes to her sister—maybe because she’s tired of being alone. Her sister comes to visit, and it’s horrible, just this endless attack. Wendy responds to each of her sister’s transphobic statements—I’m a woman, she says, I’m not a man, my name is Wendy, do not call me by that other name, this is who I am, I can’t change, I don’t want to change. She is so calm throughout the whole interaction, and eventually her sister backs down.

I can’t stop thinking about what it must have felt like to have that conversation and not to have anyone to turn to afterward, to cry with and say: “That was really hard and terrible, I am so tired and angry.”

She’s only 21.

Later, she goes to see a sexologist, who she’s hoping will help her get hormones. She’s less assertive with him—of course she is, how fucking terrifying, to have to appeal to this representative of the medical establishment in order to get what she needs—and he dismisses her. He basically tells her what she wants is impossible. It’s demeaning and belittling and awful. All I could think about, reading this scene, crying, is that Wendy has no trans sisters or aunties or mentors to go home to. There’s no one waiting for her with tissues and a hug, no one to say, “Baby, I know. Baby, fuck him. Baby, there are other doctors. I know a guy who knows a guy.” There is no one to hold her. She only has herself.

I know community does not save us. So many queer and trans people suffer in community. But I do think community, mentorship, trans friendship, queer family—makes life possible. Seeing yourself reflected in someone else makes life possible. Wendy doesn’t have any of that, and she’s trying anyway. She’s trying so hard to live.

Very little is known about Geoff Brown. He lived as a man and was married to a woman. Was he trans? It’s hard not to wonder, because this novel feels like it was written from the inside. It is not cheap or simple. It is deeply painful and deeply empathetic, raw and real and tender. But we’ll never know. He’s dead, and he can’t tell us. So I’m thinking about the burden of proof, and the weight of responsibility. Maybe Brown was a cis dude. And maybe he was trans, and this novel was the only way he could express himself at the time. I choose to honor that. I think we owe it to Wendy, and to Brown, whoever he was, and to all the queer and trans people who did survive—to listen to their stories, to keep telling their stories, to wade into the muck with them, uncertainty and all.

At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid (Short Fiction, 1983)

I read this thanks to Kiki (@ifthisisparadise on Instagram), as part of her amazing Jamaica Kincaid readalong. I went back and forth about whether to include it here, because it feels like this book and I are just getting to know each other. I read it in one big gulp, hungry for Kincaid’s gorgeous prose. I let the words wash over me, a wave of sensation, like water flowing over and through me, unstoppable and fast. This is how I often read poetry: I let my brain go quiet. I let go of all the context I’m probably missing, all the subtleties, all the riches hiding in the spaces between the worlds. There’s something particularly thrilling about reading complicated, challenging texts this way, at least the first time. It’s a way of giving myself permission to treat a book like a friend, the beginning of the conversation, a doorway, or, in this case—a rushing river, a mossy knoll, a waterfall. Something beautiful to marvel at rather than a mystery to analyze and unpick.

So my thoughts about this remarkable little book, for now, are all feeling. My brain wasn’t online when I read it. Everything about how I connected with it has to do with the body. This is not the only way I want to engage with it. I’m looking forward to delving into all of the incredible scholarship Kiki has shared, and I’m hoping that my second read will be stiller and slower—like looking into the depths of a deep, clear pool.

For now: This book is sticky and slippery and sweet, it’s water and grass and mountains, green growing things, sky and dirt and root. It’s lush, it’s longing, it’s all the secret places between knowledge and memory, body and spirit, it’s bone old and rushing. It’s about being between, I think, it’s about some kind of queer formlessness, I think, the shapes we inhabit in the dark, the places we go when the world cracks us open. It’s about light and the way it moves through bodies. It’s about home and loss and what it means to journey back and forth between them. It’s tree deep and playful, and if there’s any magic in it, it’s the magic of moving through water and the magic of biting into sweet fruit and the magic of night-scented flowers.

The prose is thick, chewy, it bites, and the narrators of the stories are elusive, wondering and wandering, mothering and lost, they’re all unbuckling and untangling their womanhood, I think, trying to figure out how it fits inside their skin. They slither through longing, seeking and striving, looking—for a place to rest and someone to rest with, for a method of dispersal, for quiet.

Kincaid writes about queer relationships: “Now I am a girl but one day I will marry a woman—a red-skin woman with black bramblebush hair and brown eyes, who wears skirts that so big I can easily bury my head in them.” I mean. Gay and sexy. But more than that, there’s a queer restlessness in her writing, a queer refusal to adhere to form. This book is a queer feeling behind my eyes, a gut flutter, a persistent hook, mysterious and sad, rooted now in my fingers and my blood and the air whooshing through my lungs.

We Both Laughed in Pleasure by Lou Sullivan (Journals, 2019)

This was one of the best books I read in 2022, and though I’ve mentioned it before (in last week’s essay, in my Best Nonfiction of 2022 list), I haven’t reviewed it yet because it feels too precious, too close. I don’t think I’ll ever find the words to capture just how perfect it is. But it feels right to write about it this week, alongside I Want What I Want, because it is proof of a different kind of trans life, because Lou Sullivan is absolutely not fictional, and he left an incredible record in these diaries. He speaks for himself, and he has so much to say, so much to teach. His journals feel like a sacred text, something hard and beautiful to cherish and ponder and laugh over and give into the hands of everyone.

This brilliantly edited collection is only a small fraction of Sullivan’s journals, but they cover a vast span of years, from when he was about 12 until he died at 39. He writes recklessly and beautifully about everything he feels and thinks and experiences, and at the heart of all this putting-it-down-on-paper is change. How he feels about himself and his gender, sex, love, his body, music, work, family, activism, community—it changes and changes and changes. There is so much reductive rhetoric these days around “certainty” when it comes to queer, and especially trans, identities. As if being certain about something is what that makes it true. As if knowing yourself absolutely is a fair requirement for access to medical care, etc. Lou Sullivan’s chaotic journey to and through self stands in glorious opposition to that small, binary thinking.

His story is not a simple story. Is anyone’s life a simple story? It’s about transformation and muddling through and fluidity. There is so much freedom and healing in reading through Sullivan’s revelations and redemptions and reinventions. We do not have to be one thing. We do not have to stay the same. We do not have to be certain. We do not have to be still.

What a gift to hold this funny, sexy, horny, contradictory, loving, angry, passionate witness of a queer trans life in my hands, every mundane and remarkable story Sullivan tells. What a blessing to bask in the trans joy that overflows and flows and flows in these pages. What an honor to listen to this voice of a queer ancestor, who should be here, who is not here, who left this utterly charming and ridiculous and gorgeous record of his life, his work, his loves, his body and mind and dreams and messes and joys. It is heartbreaking, it is miraculous. And while I'd trade it all away for Sullivan to be living happily in gaudy gay retirement somewhere, for all the queer elders who did not survive the 1980s and 1990s to be here, I can’t. All I can do is listen to them with my whole being, and let their words become a part of me.

The Bake

I cannot connect this recipe to ancestry, or ancestral tenderness. I can say that I made this because I had a sudden craving for quiche. I haven’t made a quiche in years! So have a little tenderness for yourself, and follow your baking cravings, when you can.

Creamy Mushroom Quiche

Friends, it’s so basic. Add garlic, add other veg, use different cheese, add other herbs—do what you want. Or make it just like this: basic and delicious.

Ingredients

For the crust:

2 sticks (16 Tbs/227 grams) cold unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

240 grams (2 cups) all-purpose flour

pinch of salt

2-4 Tbs ice water

For the filling:

1 medium onion, sliced

8 oz. cremini mushrooms, sliced (about 10)

1 cup cream

6 eggs

2 scallions, sliced

2 cups cheddar, grated

salt and pepper

Make the crust: Put some cold water in a bowl with ice and set aside. In a mixing bowl, combine the flour, salt, and butter with your fingertips. To keep the dough from getting too warm, dip your fingers in the ice water every now and then. Mix until it resembles coarse sand (some larger chunks of butter are okay). Add the water a little bit at time, mixing with your fingertips between each addition. When the dough mostly holds together, dump it on the counter and knead it a few times to gather into a ball. Flatten into a disk, wrap with plastic wrap, and stick it in the fridge. (You can also do this in a food processor, and you don’t have to chill it. This dough is forgiving; I’ve rolled it out hundreds of times without chilling.)

Bake the crust: On a lightly floured surface, roll out the dough into a 14-16” circle. Drape it over a 10” pie dish and gently mold the dough into shape. Trim the excess, but leave about an inch of overhang. Prick the bottom all over with a fork.

Butter the shiny side of a piece of aluminum foil and press it over the dough. Line with pie weights, dried beans, or rice. Bake at 400 for 25-30 minutes, until golden. Let cool completely on a wire rack. Trim the excess to create an even top.

Make the filling: Heat a knob of butter in a skillet over medium heat , and sauté the onion until soft and translucent, about 15 minutes. Add the mushrooms and cook until soft and nicely browned, another 6-8 minutes. Set aside to cool slightly.

Whisk together the cream and eggs in a large bowl. Add the scallions (chives would work well, too—I didn’t have any), cheddar, salt and pepper, and onion-mushroom mixture. Mix well.

Assemble and bake: Pour the filling into the prepared crust. Bake at 400 for about 35 minutes, until the top is golden brown and the center is just set. Let cool to room temperature before serving.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Cauliflower & Chickpea Pasta

When I cook, I usually make recipes that feed 5-6 people, so that I have enough to feed myself for several days. Most of the time I’m perfectly happy to eat the same meal three nights in a row. But sometimes I am downright ecstatic about it. Sometimes I make something so delicious that just the thought of getting to eat it again—and again and again!—makes me happy. I’m not sure what kind of magic is going on with this creamy cauliflower pasta, but I would have happily eaten it for another week.

In a large pan or dutch oven, sauté 2-3 medium onions in butter (or olive oil). Add a bunch of pressed garlic cloves, at least 5, and continue cooking on low heat until the onions have softened. Break up a head of cauliflower into florets. It’s better if they’re small; you can cut the bigger florets into pieces. Add the cauliflower to the pan, along with 2-3 cups cooked chickpeas, 2 cups broth (I used the broth leftover from cooking the chickpeas, but any kind will do), a handful of sun-dried tomatoes, salt, and pepper. Simmer until the cauliflower is tender. Add 2/3 cup cream (or so) and stir to blend. Remove about 2 cups of the mixture from the pan, puree with an immersion blender, and return to the pan. Mix well and adjust seasonings.

Toss with a pound of cooked pasta, a big handful of chopped parsley, a few tablespoons of capers, 3-4 ounces goat cheese, and a lot of grated Parmesan.

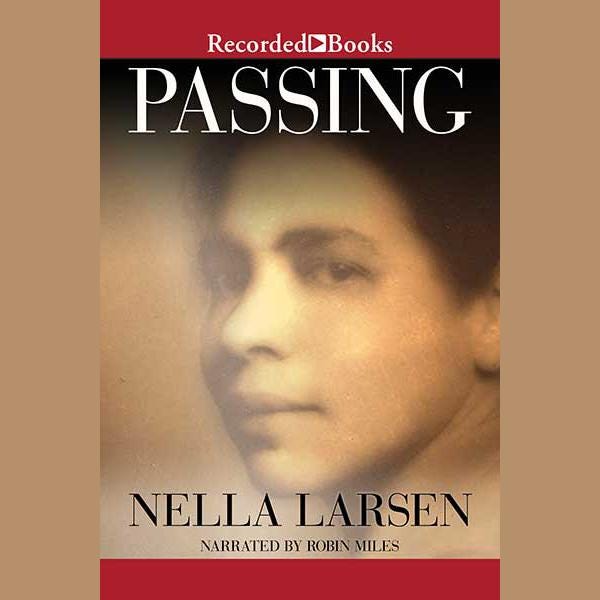

The Beat: Passing by Nella Larson, read by Robin Miles

Raise your hand if you’re surprised that the audiobook I just finished is a queer-coded classic published in 1929. I read this for the first time in 2018, and returned to it spontaneously over the weekend because I’ve been immersing myself in Black and queer 20th century lit and history, and I don’t plan on stopping anytime soon. It’s a brilliant book, just masterful, basically a perfect novel. The queer subtext is right there, waiting for you if you need it, easily missed if you don’t. It got me thinking about subtext in general, and the history of queer-coded narratives, and why they matter—just as much, I think—as more obviously queer texts.

The Bookshelf

A Portal

Recently I’ve been drawn to older texts (as evidenced by this entire newsletter) as well as sticky, challenging texts. I’m not sure where this desire is coming from, but I’m following it. And because many of these books require careful attention and slow untangling, I’ve been thinking a lot about reading rituals, and experimenting with how to create reading spaces/moments that feel sacred and inviting. Over the weekend that involved late afternoon tea at my desk.

I’d love to hear about your reading rituals, if you have any!

Around the Internet

Looking for some inspiration for your TBR this month? I made you a curated queer TBR for February! On BookPage, I reviewed Call & Response by Gothataone Moeng.

Now Out / Can’t Wait!

Now Out

Hurray! Choosing Family by Francesca T. Royster is now out! I adored this memoir.

I am also eager to get my hands on a copy of Couplets by Maggie Millner. It’s a queer love story told in rhyming couplets. Sounds wild and perfect.

Can’t Wait!

World Running Down by Al Hess (Angry Robot, 2/14): A weird queer speculative adventure with AI? Sign me up.

Dyscalculia by Camonghne Felix (One World, 2/14): I loved Felix’s poetry collection Build Yourself a Boat, so I’m excited about this memoir.

Queer Your Year

News & Announcements

The January raffle is now closed. Thanks so much to everyone who participated, and congrats to Emily, who won the Fertile Futures calendar! For those of you who submitted a game card with any of the winning prompts completed, prize packs went out in the mail last week. I had so much fun making them, and I hope they bring you a little bit of joy.

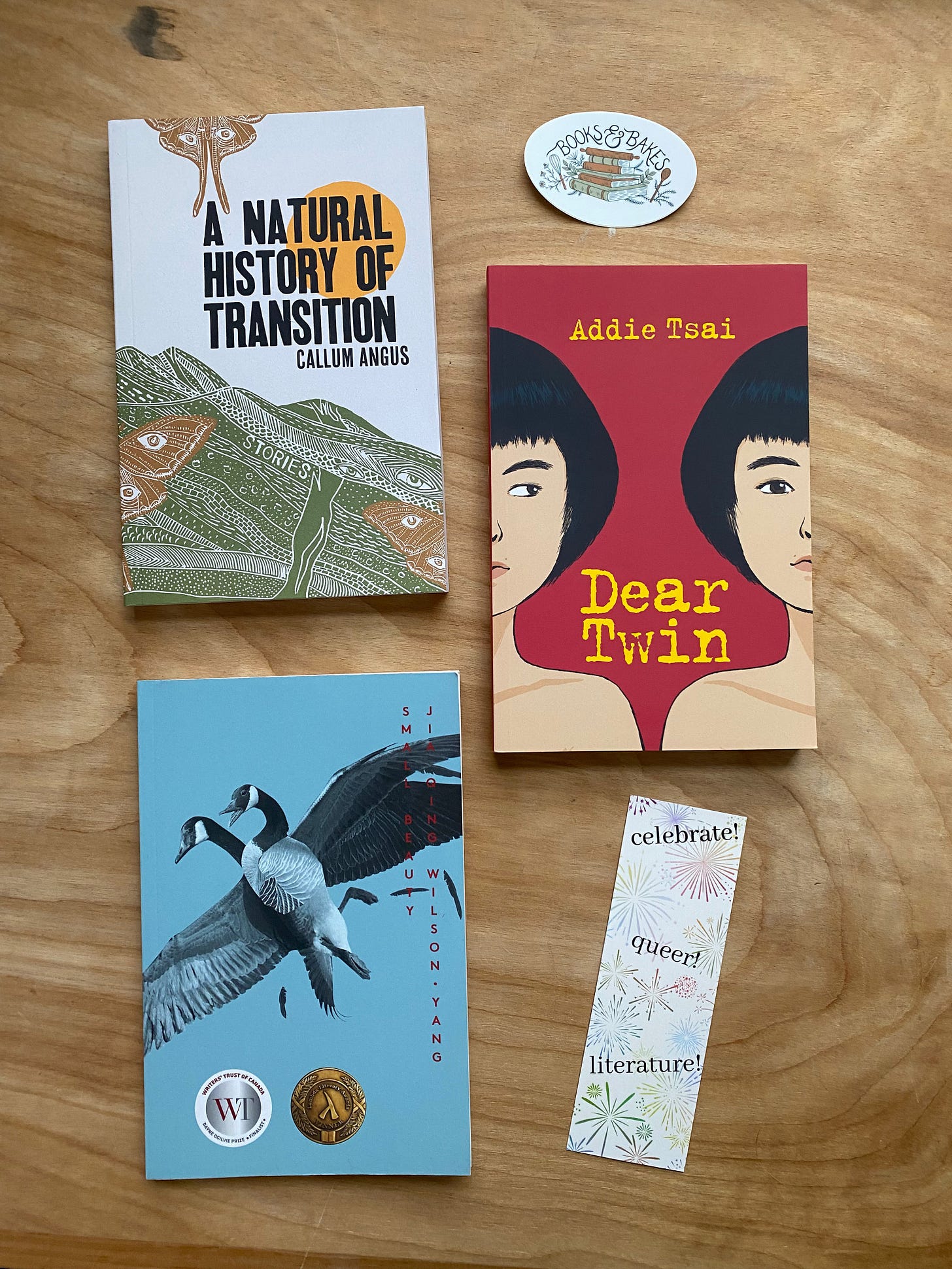

The February prize is an exciting one: a queer book bundle from Metonymy Press! Metonymy is an amazing queer publisher based in Montreal. The bundle includes three of my favorite Metonymy titles: A Natural History of Transition by Callum Angus, Dear Twin by Addie Tsai, and Small Beauty by Jia Qing Wilson-Yang.

Recs!

Prompt 3: A book published before you were born

When I came up with this prompt, I didn’t realize that 20th century queer lit was going to be the theme of my reading year. So two of today’s books work for this prompt (for me), and obviously I recommend them! Here are a few more I love:

Books that will work for everyone (unless I have any 94-year-old newsletter readers): Alexis by Marguerite Yourcenar, tr. Walter Kaiser (1929)—easily my favorite book of the year so far; Harlem Shadows by Claude McKay (1922)—playful, multifaceted poems.

Books that will work for a lot of you: The Tree and the Vine by Dola de Jong, tr. Kristen Gehrman (1954)—messy sapphic excellence; Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin (1956)—it goes without saying, right? It’s on my reread list.

Books that will work for some of you: Fair Play by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal (1989)—quiet sapphic excellence; The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde (1980)—still so relevant and vital.

Prompt 6: A novel (or story collection) set in a rural place

I love rural queer fiction, and I’ve reviewed a lot of it here! These books are set in all sorts of rural places—wilderness, small towns, farm country, remote lakes, isolated islands. None of them are about cities. Rural lit is so rich and varied, and these extremely different books prove it. Links go to my reviews.

Fire Song by Adam Garnet Jones; The Memoirs of Stockholm Sven by Nathaniel Ian Miller; Silhouette of a Sparrow by Molly Beth Griffin; A Minor Chorus by Billy-Ray Belcourt; Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro; Polar Vortex by Shani Mootoo; Weekend by Eaton Hamilton.

The Boost

Book Giveaways for a Cause!

Last week, I donated $35 to Lavender Phoenix. Thanks so much to everyone who participated!

I have six books to give away this week. In case you missed it, here’s the deal: I’m giving away books in exchange for donations. Drop a comment indicating which book you want. The first commenter for each title will get that book; I’ll email you with instructions on how to pay. Once I’ve received payment, I’ll mail your book to you. All the money, minus the cost of shipping, will go to the week’s chosen organization. As always, if you’re able to donate more than the cost of the book, I encourage you to do so. Additional details about how it works are here.

This Week’s Money Goes To…

…The Trans Asylum Seeker Support Network (TASSN). The violent and dangerous transphobic legislation just keeps coming and coming. The ACLU is tracking all the anti-LGBTQ bills in the U.S. and I cannot look at this map without breaking down in rage and grief. It is terrifying. One of the small ways I try to help, when I can, is by giving to organizations and collectives that are led by, and work directly with, the people most affected by these hateful attacks. TASSN “is a grassroots collective and not a non-profit. All funds we raise as a collective go to paying stipends, rent, and medical and legal costs for trans and queer asylum seekers.”

Ready? Check out This Week’s Books!

This week’s theme is: ancestral books, loosely.

The Boat by Nam Le (Paperback, $10): It’s intense and kinda bleak, but I remember loving it.

Arcadia by Lauren Groff (Hardcover, $15): Communes! Messes!

The Farming of Bones by Edwidge Danticat (Paperback, $10): Dark, beautiful. I think most of what she writes is like this?

Homestead by Rosina Lippi (Paperback, $10): I read this ages ago and loved it.

Things That I do in the Dark by June Jordan (Paperback, $10): Looks like this is out of print, so lucky you!

The House of Rust by Khadija Abdalla Bajaber (ARC, $8): A magical coming-of-age story set in Kenya, with bone ships and talking animals.

Several of last week’s books are still available—and they are all fantastic reads! Check them out here, and drop a comment if you’re interested. The money will go to TASSN.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: My pup is recovering from surgery on her knee, so we’re just doing 10-15 minute walks up and down the road, but the sunsets from my yard are gorgeous.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! Next week’s essay will (most likely, no promises) be about At the Pond, one of my favorite books from last year, and swimming, and my relationship with water. If you want to read it, you can subscribe here.