Greetings, book-chompers and treat-makers! I am doing an experiment this week where I don’t read. At all. I read a lot and I love it (obviously), but recently I’ve been wondering what would happen if I didn’t spend all my free time reading. What kind of space would open up for other joys? I’m on day three of this experiment, slightly grumpy about it, and not sure that a week-long reading ban is the best way to invite balance into my life. But I have been listening to music, including several new-to-me artists, and that is exciting.

In other news, I started a commonplace book! A commonplace book is just a collection of quotes and passages from books you’ve read. I was inspired by this article by my fellow Rioter Ashley (she’s been keeping one for over ten years!), and decided to take the plunge. I’ve wanted to start one for a while but the thought of another handwritten journal has always intimidated me. I write in my journal every day, and my hands already hurt enough from that (hello, 12+ years of farming). But Ashley’s article reminded me that digital commonplace books are also valid.

I played around with a few different websites and apps, and decided on Notion. I love it. I can add photos and tags to each entry, browse through the quotes in different ways, and organize it all exactly how I want it. (Unlike Tumblr, which I will never understand.) I’m still adding quotes I’ve flagged from books I read earlier this year, but you can check it out here.

Moving on. Coming home: it’s complicated. It’s painful. It’s a mess. It’s joyful. Sometimes it’s not even possible. All of these books are about home-leavings and homecomings—some small, some monumental. Home—the physical place, the memory of it, the dream of it, what it can never be, having it, losing it, who it turns us into—shapes our lives. These books approach what it means to come home in different, beautiful ways.

The Books

Backlist: Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray by Anita Heiss (Historical Fiction, 2021)

Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what makes me love a book so much. This usually happens when I become so immersed in a story that I get lost in it. Then it’s almost impossible to see exactly what the author is doing, because all I can see is the story itself. That was my experience of reading this book. I listened to it last December, during Cookie Extravaganza, and I would often find myself standing in the middle of my kitchen, spoon in hand, unable to remember what I’d just been doing because my entire focus was on the book.

The story opens in Gundagai, in Australia, in 1852. Wagadhaany, a member of the Wiradyuri Nation, lives with her family along the shores of a massive, powerful river. Wagadhaany and her people know not to settle too close to the river, but the white colonizers ignore their warnings and build a town on the floodplane alway. After a flood destroys the town and kills many of its residents, Wagadhaany, who works for a white family, is forced to move away with them to another part of the country. She leaves her own parents and family behind. She’s forcibly separated from the homeland that she loves.

The whole novel, after this initial separation, is the story of Wagadhaany trying to make her way back home. It’s made up of ordinary moments—but so many of these ordinary moments are small incidents of violence and violation. Louise, the wife of Wagadhaany’s employer, is a Quaker and a reformer. She begins to think of Wagadhaany as a friend, but (of course) she’s paternalistic and condescending and sees her as a project and not a whole person.

Wagadhaany is desperate and unhappy, trapped in a life she didn’t chose. She knows what she has to do to survive, and she hates it, even while making choices that keep her alive. She’s also a thoughtful, playful, caring person: she sees the ways Louise herself is trapped. This knowledge doesn’t pardon Louise. But Wagadhaany, as the narrator of her own story, is willing to witness the complexity of the world around her. She doesn’t reduce herself to her suffering. She knows who she is, and where she belongs, and what she wants. She doesn’t let go of that even when it would be easier to do so. And she brings that calm certainty, that deep knowledge of her own heart, to the way she sees the world. This is a devastating book about the colonization of Australia. But it is also a book about the beauty of a place, and about the joy and power and solace of knowing what it means to belong to a place.

Wagadhaany’s longing for her home and her family never goes away. It doesn’t get easier. She finds comfort when she becomes close with the local Aboriginal people, and she eventually falls in love with one of them and starts a family of her own. There’s real tenderness in the way Heiss writes about this second family. There are sections of this novel that are bursting with joy; at times it is outrageously, raucously, wonderfully loud. It’s a loud as the violence is. Yet despite Wagadhaany’s love for her husband and his people, her need to return to her own homeplace never abates. Her longing for it drives everything she does.

She’s one of the most interesting and specific and fully realized protagonists I’ve had the pleasure to spend time with in recent memory. It’s her voice, her particular wants, her vantage point, her heart—that drives the book forward. She experiences immense change. She grows up, becomes somebody’s lover, somebody’s mother. She grows edges, teeth. But through it all, she holds on to some essential piece of herself. It’s a beautiful journey to witness.

Frontlist: South to America by Imani Perry (Nonfiction)

I listened to this book a few weeks, and I absolutely loved it, but I’m going to be honest with you: I let Perry’s words wash over me. I meandered with her through the South, from DC to West Virginia to Atlanta to New Orleans to rural Alabama to the swamps of Florida. I let her stories carry me, let the rhythm of her prose (and her narration) sink into my heart and—a little bit—into my brain. I learned a lot and I felt more, but this is a book that deserves a close and careful reading, closer and more careful than the weekend I spent listening to it. Which is to say: it’s going on the to-buy-in-print-and-reread list.

It’s an extremely smart and nuanced book about the South and its central place in the founding, history, mythology, and present of America. It is an essential history; a deep dive into Southern politics, food, geography, language, art, culture, and history; a personal story about leaving and homecoming and family and roots; a collection of interviews and visits; a reckoning with racism and white supremacy; a call to action; a celebration.

Perry is a brilliant historian and a brilliant writer; it’s a killer combo. There’s a lot of research in this book, but she presents it with urgency and passion. She makes it clear that everything she’s writing about is somebody’s reality. It’s a book that reads like a collection of deep-dives. She writes about Southern slang, dialects, and accents, and the differences between white and Black Southern language. She examines the cultural histories of cities like Atlanta and Birmingham. She delves into the the Black Power movement, civil rights, Southern food, queer art, confederate reenactment, monuments, immigration, dance, economics, literature. All of these small stories, sometimes focusing on a particular person, moment in time, or neighborhood, add up to a much bigger story about the South as a region and an idea, a physical place and a mythological one. Perry beautifully illustrates how absolutely central the South is to the United States’ understanding of itself. Thus we cannot hope to change the country at all without looking at, and understanding, the South.

I reviewed the audiobook here, and I highly recommend listening to it.

Upcoming: Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Fiction, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, July 12)

Towards the end of this novel, the two main characters—Rafik, a Pakistani politician farmer, and Fahad, his queer son, are having a conversation. Fahad has spent most of his adult life in London, and has returned to Pakistan to help his parents, who are in financial trouble. They are discussing what to do with the family farm in Abad, land that Rafik’s family has owned for generations. For both Rafik and Fahad, the farm is a mythical beginning, an idealized homeland, at once beloved and unknowable. It is central to their understanding of themselves but also a source of endless confusion and pain. Rafik says to Fahad:

‘Sometimes you don’t know what you remember and what you think you remember. Sometimes, even my father’s face, when I remember it, it is one way, sometimes another. But what is there to be afraid of? A man is more than his face. He is more than the places he has been. And the places he has been, they are in here’—again he tapped his chest—‘nowhere else. We carry it where we go. Everything. What does it mean to leave?’ he said. ‘We can only leave ourselves.’

This whole novel—quiet, hypnotic, sad and soft, a book that floats along like seeds on a breeze, drifting here and there, never settling—reads like an attempt to untangle the questions buried in this passage. What does it mean to leave? Can we ever leave the places that have shaped us? Is a person more than the places they’ve been, more than their face? And what does it mean to ‘leave ourselves’ somewhere? Neither Rafik (despite his confident assertions in the quote above, a hallmark of his character) nor Fahad ever come to any definitive answers. They spend their lives muddling through—as so many of us do.

The novel is split into two sections, both told in alternating POVs between Rafik and Fahad. The first is set in Abad, in northern Pakistan. Fahad is sixteen, spending the summer with his father at the family farm for the first time. He’s resentful about it; he doesn’t get along with his father at all, and he’s spent previous summers with his mother in London.

In Abad, he becomes close with a local boy, Ali. They spend the summer together—fall in love, or lust, or friendship. It’s one of those intense and hard-to-label teenage relationships that becomes defining for Fahad. Soomro’s prose is gauzy and full of implications and subtext. He never explicitly states what happens at the end of the summer, but Fahad leaves, returning first to his mother in Karachi, and eventually to London.

The second section is set nearly 30 years later. Rafik has become a somewhat influential politician in the Pakistani government. Fahad, living with his partner in London, agrees to return home to help his parents sort out Rafik’s financial mess. The big question is whether or not they’ll have to sell the farm.

I loved this book, and yet, while reading it, I often felt slightly removed, as if each scene, each detail, every interaction between characters, was just out of reach. Reading the chapters in Fahad’s POV, especially, I found myself wanting to tear off some kind of covering and look beneath the words on the page. At first this was disorienting. But then I started to see exactly what Soomro was doing with the narrative, and that’s when the book shifted from “good, but I can’t quite connect” to “wow, I cannot look away from this.”

The whole book is about a man holding himself apart from himself. Fahad is observant, analytical, even, and yet he doesn’t want to look directly at the summer that became so foundational to his life. Even in the first part of the book, when he’s living through the memories that will later haunt him, he doesn’t want to look. When he and Ali kiss for the first time, he tumbles into the moment, and then he claws his way out of it, looking at it as if from outside himself, observing that “they could not make gifts of their bodies one to the other because their bodies were not theirs to give.” He’s falling in love with a place, with a person, with a part of himself, maybe—but even as it’s happening, he’s already running. He’s already looking away.

The not-looking becomes the central pillar of his adult life. It’s so sad and poignant and beautifully subtle. Even though we only see Fahad in these two moments—at sixteen, and then in his late forties—and even though he’s constantly withholding pieces of himself—he ends up leaping off the page. He becomes visible to us, the readers. It’s a delicate opening, a slow, painful, reveal, one that feels like it takes years, when in fact, it’s just a 250-page novel.

Rafik’s trajectory is entirely different, though no less moving. At first he’s brash and certain, loud, unwilling to listen to others. But he loses that certainty with age. The loses that have defined his life—the death of his cousin, his relationship with Fahad, the farm itself—become more obvious as he himself becomes less sure of his place in the world.

I’ve already gone on for too long, and that’s how I know a book has truly landed with me: if I come to the end of a review and want to keep writing. I want to write about all the complicated ways Soomro interrogates the possibilities and impossibilities of home. I want to write about the soft queerness in this book, the weaving together of deep shame and pain and loss with wild, beautiful freedom. I want to write about how silence and haunting add texture to this story, about the weight of Fahad and Rafik’s lived but unwritten years. But I won’t. I’ll leave you with this beautiful passage:

What had he been so afraid of? That coming back would precipitate some sort of crisis? That it would surface memories that unmade him? That it would return him to some earlier state—of doubt, of weakness, of wanting to disappear? It was nothing at all, it was only a place, only people, and earth and sky, roads and cars, and walls, men and women and children.

The Bake

I have baked a lot of desserts in my life: medium fancy ones, like this rublitorte; extremely fancy ones, like this peach pavlova; and absurdly fancy ones, like this three-tiered birthday cake. But apples, I think, are my baking root. Baking with apples always feels like coming home. They’re my favorite fruit. (What can I say? I am a coldblooded New Englander who can only handle the sun in small doses.) You can transform them into lofty cakes like this, or artful tarts like this, or the simplest, quickest, most comforting, whip-it-up-on-a-Tuesday-night crisp. That’s what this is. The caramel sauce makes it a little fancy, sure. But you can make it in advance (it’s really nice to have around). Or just buy some!

Caramel Apple Crisp

Ingredients:

1/2 cup (180 grams) caramel sauce (I had caramel sauce I made from the Tartine cookbook left over from Cookie Extravaganza; it’s basically this recipe. Store-bought sauce will work just as well!)

4-5 small-medium apples

1/4 tsp cinnamon (if you want)

85 grams (3/4 cup) all-purpose flour

115 grams (1 cup) oats

1 tsp cinnamon

30 grams (3 Tbs) brown sugar or maple sugar

1/2 tsp salt

10 Tbs (141 grams) cold unsalted butter

Preheat the oven to 350.

Peel and core the apples and cut them into small chunks. Dump them into an 8-inch square baking dish and pour the caramel sauce over them. (If you’ve just made it, let it cool to room temperature first. If you’re using it from the fridge, it’ll be easier to mix if you let it set on the counter for 15 minutes.) Sprinkle the cinnamon on top. Mix well with your hands until all the apples are evenly coated.

Make the topping: in a small bowl, combine the flour, oats, cinnamon, sugar, and salt. Cut the butter into small chunks and mix with your fingertips until you have a clumpy, sticky mixture. Spread it on top of the apples in an even layer.

Bake for 30-40 minutes, until the top is crisp and golden brown, and the apples are starting to bubble up from underneath. Let cool slightly before serving.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Sheet-Pan Sumac Chicken & Cauliflower

I’m doing a thing this year where each month, I pick a cookbook as my “Cookbook of the Month”. It’s basically a way to jumpstart my kitchen imagination. Or something. It’s not like I’ve been cooking up a storm, but it’s been fun. This month’s cookbook is Flavors of the Sun by Christine Sahadi Whelan. I have yet to make a single recipe from it, but I did use it as the inspiration for this delicious meal. The seasoning is almost identical to one of Whelan’s recipes, but I tossed in my own veggies.

Put some chicken pieces (2-3 pounds, thighs, legs, breasts, whatever) in a bowl. Add a few tablespoons of sumac, a few pinches of dried thyme and/or oregano, a sprinkling of cumin seeds, one teaspoon salt, and a cup of olive oil. Press a few garlic cloves into the bowl. Add the zest of a lemon. Make sure all the chicken pieces are nicely coated and set aside while you prepare the veg. Preheat the oven to 350.

Cut a head of cauliflower into florets and arrange on a baking tray. Drain a can of chickpeas and add them to the pan. Cut 1-2 red onions into thick slices and add them, along with a lemon, thinly sliced into half moons. If I had any sweet potatoes around, I would have chopped one up and added that. Nestle the chicken pieces in and around the veg. Dump the remaining marinade onto the pan and mix with your hands so it coats all the vegetables. If you need to, add more olive oil (it will depend on how many veggies you do). Bake for 45 minutes or so, until the chicken is nicely browned and cooked through. Stir the veggies around once halfway through the baking.

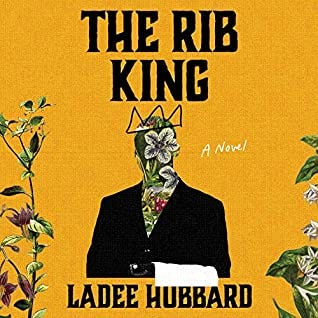

The Beat: The Rib King by Ladee Hubbard, read by Korey Jackson and Adenrele Ojo

I am not currently listening to an audiobook and I hate it. It’s by far the hardest part of this whole not-reading week. But I inhaled this one last weekend! It begins in 1914, at the house of a wealthy white business owner. The first section is narrated by one of the Black servants who works in the house; the second section is set 10 years later, and is narrated by a different former servant, a Black woman who is now a successful entrepreneur. It is a a superb character study, a beautifully subtle and surprising story about revenge and the uses of violence. It is so sharply done. I’m still digesting all the nuances of it.

The Bookshelf

The Visual

How did I get so many bookmarks? I have jars of them all over the house. So I’m doing a giveaway! Why not?

Bookmarks aren’t that exciting, I know, but snail mail is! Leave a comment (or reply to this email) and I’ll randomly select three winners to receive a snail mail pick-me-up package with a few fun bookmarks.

Around the Internet

For Audiofile, I wrote about three very different immigrant stories, all fantastic on audio. On Book Riot, I wrote about how much I love waiting years for a new book by a beloved author.

Now Out

Horray! Bitter by Akwaeke Emezi is now out! I enjoyed it a whole lot.

Bonus Recs about Coming Home

I recently read Boys Come First by Aaron Foley, thinking I might write about it this week. I didn’t love it enough to rave about it, though—too many quick and choppy POV switches. (I am absurdly picky about this.) However, I still enjoyed it! It’s about three Black gay men in Detroit, one of whom has just returned home after years in New York. It’s fun and lighthearted (mostly) and quite funny. It’s out May 17th.

And for all my SFF fans out there, two books I read last year but likely won’t feature here: This Poison Heart by Kalynn Bayron and After the Dragons by Cynthia Zhang. Both are lovely, and feature different kinds of homecomings.

The Boost

Some tidbits:

I have yet to order any seeds, but I am certainly dreaming of gardens. If you are too, check out this list of Black-owned seed companies!

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I usually share pictures of the natural world here, but obviously there are many beautiful things on this earth that are not photos of nature. This is also very beautiful. So is this. And this! (Yes, I know, that last one is nature.)

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

Ah! I'm so happy that post inspired you to start a commonplace book! Yours looks so great. I know I shouldn't move mine from Tumblr to Notion, but this is enticing...

And kudos on not reading. I hope you find some extra joy in your world!

Hmm—not reading. And not listening. The following is somewhat of a tangent, but is has me thinking about quiet time.

For context, I've living with four other people during the pandemic, so I don't get much quiet time. I also am on about fifteen hours of work calls each week.

Times I like listening to audio books:

* When I'm doing chores around the house, like folding laundry or washing dishes

* When I'm driving

Times I like quiet (no books, no music):

* When I'm in the sauna (about three hours per week)

* When I'm exercising—mountain biking, cross-country skiing, trail running (four hours per week)

* When I'm walking the dog—although sometimes I'll use this time to call a friend or family member (six hours per week)

Anyways, I really appreciate the approximately eleven hours each week (outside of sleeping) that I get to be in a more meditative state of silence!