Greetings, book people! Thank you for being here. It truly means the world to me.

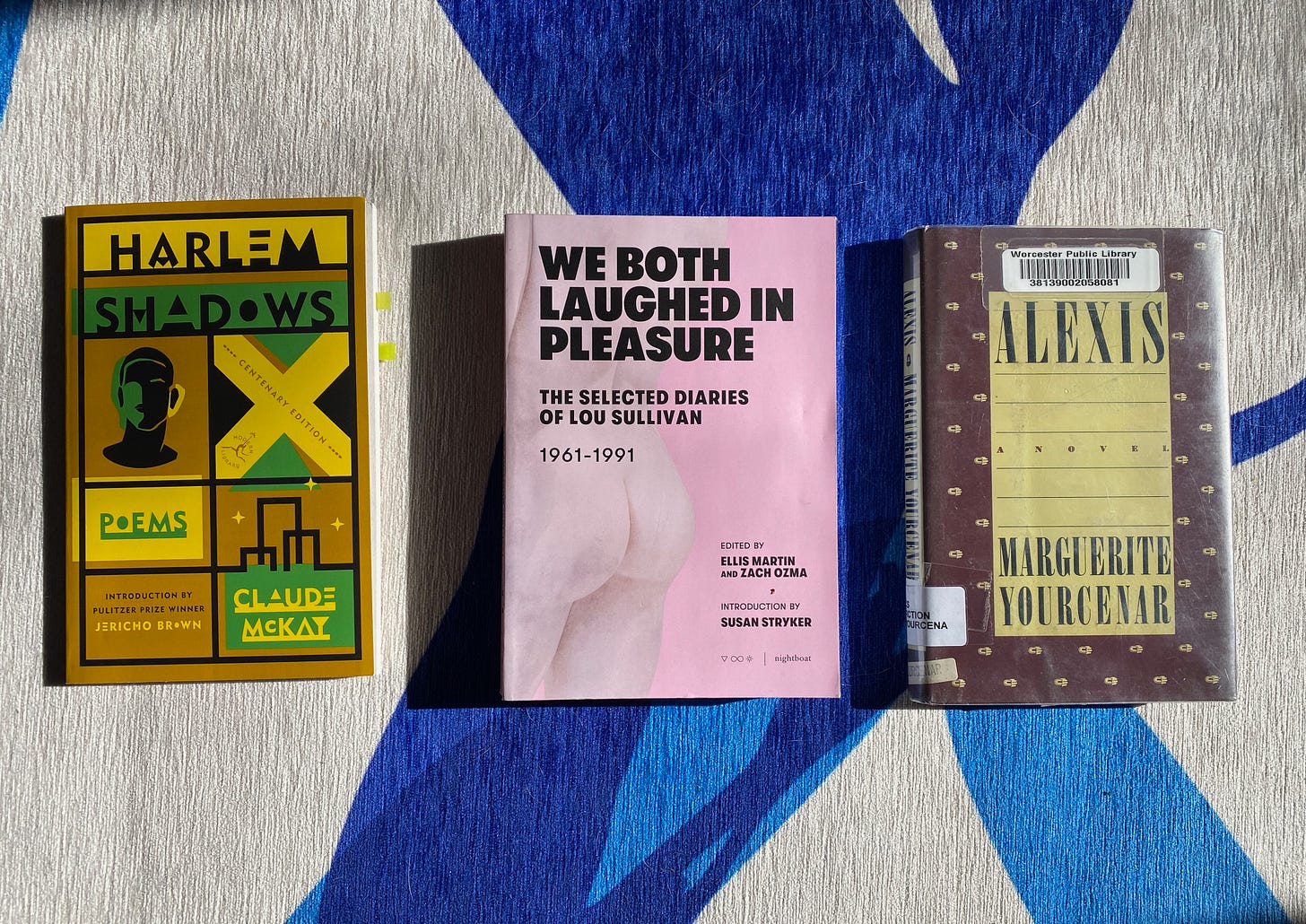

The best books I read in January were all queer books published in the 20th century—Alexis by Marguerite Yourcenar, Harlem Shadows by Claude McKay, and At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid. So I’ve been thinking a lot about queer literary ancestry. I’ve been thinking about it since reading Lou Sullivan’s brilliant diaries We Both Laughed in Pleasure last year, and, truthfully, for a long time before that. I am always grappling with it. Sometimes it feels like the defining question of my life as a queer reader and writer: what does it mean, not only to honor, but to truly see, my literary history and lineage? This piece doesn’t include all I have to say on the subject. It is merely the beginning of a lifelong untangling.

This essay includes “spoilers” for Alexis and the film My Beautiful Launderette. I don’t think anything I write here will detract from your enjoyment of either work, but fair warning.

In his brilliant introduction to Harlem Shadows, poet Jericho Brown writes:

And though scholars argue over whether these poems make clear McKay’s queerness—he was bisexual, frequented gay venues and parties, and had erotic relationships with both men and women throughout his life—it is always important for us to remember that none of these poems would have been written if he had not been queer. All art is the product of the entirety of an artist’s life, whether that art is biographical or confessional or neither.

The poems in Harlem Shadows aren’t queer in the way that most contemporary readers would define it. They are about many, many things: being homesick for Jamaica, everyday Black life in Harlem, waiters and dancers and sex workers, winter, flowers, moments shared with a lover, protest, racism in America, state violence. They are by turns playful and elegiac. I was not expecting to love them in the way I did. I was also not expecting them to be so queer, even though I knew McKay was queer. Perhaps this is because they are queer in exactly the way Brown describes. Their queerness isn’t direct or explicit. It’s a feeling, an old knowledge that lives in the body, a sureness and familiarity.

We have always been here is a phrase that I, along with many others, have used over and over again. I suspect I’ve written it in this newsletter. For years, it was one of the tools I used to fight back against the idea that queerness (and transness) is new. Reading historical fiction featuring queer characters, waving Leaves of Grass around like a flag—these were concrete embodiments of the we have always been here philosophy that I embraced. We have, yes, always been here. But reading Jericho Brown’s words, and then reading McKay’s poems, solidified an unease with the idea that has been growing in me for months.

I’m thinking of Claude McKay, putting all of himself into his poems—his queerness, his Blackness, his identity as Jamaican and American, his obvious love of the natural world—and I’m thinking about how I might not have called Harlem Shadows a queer book a few years ago, and I’m thinking about the ways that we have always been here is a kind of erasure. It’s an erasure because it demands proof.

I have never liked that famous Martin Luther King, Jr. quote about the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice (though this article, which I just found, complicates it somewhat). It’s a simple quote, which, like so many of his most-used quotes, reduces his actions and beliefs to something hopeful and palatable. I don’t like it because, at face value, it implies that we are on some kind of straight path toward liberation. This is not an essay about Martin Luther King, Jr., or the history of activism, or hope. But I want to linger in this uncomfortable truth for a moment, because I think it’s at the heart of the problem with we have always been here: history does not move in a neat line from bad to good. Many things in this world have improved over the centuries. Many other things have not. In the U.S. we are living through proof of this. Abortion used to be legal, and now it is not. Time moves forward, and guarantees nothing.

When it comes to queer history, and the way queer history is represented in literature, this binary thinking about the direction of progress makes it incredibly easy to condemn queer people (and characters) from the past to lives of suffering, and elevate queer people (and characters) in the present to lives of freedom.

Enter Alexis, a 105-page gem of a French novel from 1929. The eponymous Alexis, a musician, has just left his wife, because he’s realized he cannot continue to lie to himself, and therefore to her, about his queerness. So he writes her a letter explaining his actions. It is a stunningly beautiful book. It complicates, and ultimately rejects, this trajectory of progress, this idea that once upon a time queer people suffered, and their suffering was the whole of them. Alexis is smart and sly and quite funny. He’s full of joy, and deeply conflicted. He freely admits that he spent years trying to repress his sexuality. But he refuses to incriminate himself. “What I regretted,” he writes, “was not having given in too often, but rather for too long and with too much vigor having struggled not to give in.” He has suffered, he has made mistakes, he is sad. He has also experienced “the almost sacred beauty of bread” after a long period of despair. He writes about how “music speaks to us of limitless possibilities.” In short: he is not one thing. He’s a hot mess.

I was thinking about Alexis and his messy problems last weekend, when I rewatched one of my favorite movies, and one of the greatest queer films ever made (in my opinion): My Beautiful Launderette. It came out in the UK in 1985, and in the U.S. a year later, in 1986, the year I was born. It’s about Omar, a young Pakistani man who takes over his uncle’s launderette in South London, and Johnny, his old school friend, a white street punk. It’s an incredibly tender and real romance, a complex family drama, and a bleak look at class dynamics and racism in the UK during the Thatcher years.

The last scene in the movie might just be my favorite scene in queer film history. The two leads, Omar and Johnny, are in the middle of a fight. There is a lot that is unresolved between them—Johnny’s racist history, the fact that Omar’s uncle Salim has just run over one of Johnny’s old friends with his car, their uncertain future. In the midst of all this, Johnny returns to the launderette while Omar goes to see about some potential expansion opportunities. Salim arrives, and Johnny’s ex-friends, who have been patrolling the launderette, attack him. When Johnny intervenes, they start attacking him instead. They flee when Omar shows up, but first they smash in the launderette’s windows, spraying glass everywhere.

So now Omar and Johnny are left alone in this mess of shattered glass, the temporary ruin of everything they’ve worked for, all the love and determination and care they poured into this once-shitty launderette in South London. Omar tends to Johnny’s wounds, and then they go into the back room and stand over the sink. They take off their shirts, so that Omar can wash the blood off Johnny’s chest, and then they start splashing each other, and laughing, and the door swings shut. It is sexy and playful and joyful.

What makes this scene so remarkable is the context in which this glorious moment of queer love sits. Nothing between Omar and Johnny has been fixed. Their future, though hopeful, is still uncertain. The front of the launderette is still covered in broken glass. The harsh realities of their world—racism and poverty and homophobia and their complicated history and their messy family relationships—are still there, still inside and between them. But in this moment of despair and pain, they choose each other. They choose joy; it sparks off the screen. Every time I watch this scene, I feel it on my skin. Their choice does not erase what’s going on in the world beyond the door. They cannot walk away from the world. The two of them standing over the sink, splashing each other, laughing—it’s a breath. It’s a moment of calm. It’s as real as every horrible thing they’ve each had to face, and will probably face again. It’s both/and.

This both/and moment, and the whole film, feels similar to Alexis. Both stories are imperfect and messy. They both contain so much queer joy. They’re both about struggle, but not about shame. Though set 56 years apart, their contexts feel like kin. Alexis, like Omar and Johnny, is entangled in the time he’s living through. The time he’s living through tells him homosexuality is a sickness. Tells him he ought to get over it. Tells him to buck up and marry a nice girl. He can’t escape his context, and so he suffers, but he also knows something about himself, beyond and outside of context—that he is not sick, that he deserves happiness. So he rejects the context when he can. He begins to ask different questions. “It is awful that silence can be such a fault; it is the worst of my faults, but I have committed it,” he writes to his wife. “Long before I committed it against you, I committed it against myself.” He is trying, desperately, to escape from the expectations society has placed on him. He is trying to claim his queerness. Sometimes, with breathtaking clarity, he succeeds. Sometimes he does not. We have always been here, we have always been both/and.

The last sentence of Alexis hit me right in the heart, the same way the final scene in My Beautiful Launderette always hits me. After pouring out his heart to his wife, after exposing all the truths he’s been too terrified to share, after so much explaining and pondering and wrangling, Alexis ends his letter with this sentence:

With the utmost humility, I ask you now to forgive me, not for leaving you, but for having stayed so long.

What a liberating sentence. It still gives me chills—the smallness of it, and the simplicity. Here is a queer man who has wronged someone he loves, deeply, perhaps irrevocably, and here he is admitting it. Here he is apologizing—not for leaving, an action he takes in service of his own liberation—but for the actual wrong done. There is so much queer joy in this one tiny sentence—finally, free!—and there is so much sadness, too. Alexis chooses his own joy—his very life, perhaps—but his choosing, like Omar and Johnny choosing each other in the back of their launderette, is not absolution. The world goes on, and they go on inside it. We all go on inside it. Things get better, but not easily, and not always, and sometimes they get worse. Along the way, people live their lives. Just live. “My dear, it is very difficult to live,” Alexis writes to his wife, Marguerite Yourcenar wrote in 1929, I read in 2023 and have to put the book down because my heart is beating so fast. We have always been here, but we have never been only one thing. We have always been here, broken, pieced, an assemblage of contradictions, irreducible—in 1922, in 1929, in 1985, in 2023, in every decade and every century.

Sometime in the late 1980s or early 1990s, trans writer and activist Lou Sullivan wrote this in his diary:

A big fear of mine is that I will die before the gender professionals acknowledge that someone like me exists, and then I really won’t exist to prove them wrong.

This passage, like so many of the gorgeously wise and irreverent passages from We Both Laughed in Pleasure, has been haunting me for months. I wonder what we owe the dead. I wonder what we owe our queer and trans ancestors. I wonder what we owe Marguerite Yourcenar, a lesbian, who wrote Alexis when she only 26, who lived with her partner Grace Frick (who translated all of her novels!) for over forty years in Maine. I wonder what we owe Alexis, a fictional character, I know, but I can see him so vividly, sitting by the window in a train hurtling across Europe, fleeing from one life into another, furiously scribbling a letter to the wife he has just left, daring to ink the deepest truths of his being onto the page. I wonder what we owe Claude McKay, bisexual Jamaican American writer of the Harlem Renaissance who wrote in “Heritage” (from Harlem Shadows, published in 1922):

"Now the dead past seems vividly alive, And in this shining moment I can trace Down through the vista of the vanished years, Your faun-like form, your fond elusive face."

The poem ends with this stanza:

"I cannot praise, for you have passed from praise, I have no tinted thoughts to paint you true; But I can feel and I can write the word; The best of me is but the least of you."

Lou Sullivan’s “gender professionals” will likely never acknowledge his existence, at least not in the way I think he means—his irrepressible, wholly queer existence, his unpinned, unfixed, deliciously fun, sorrowful, mixed-up, loud and laughing and lost existence. The “gender professionals”—which I take to mean the state, the academy, the patriarchy, the heteronormative family structure—maybe one day they’ll come around to the idea that we have always been here. But they will never acknowledge our existence in all its muddiness, let alone protect it, let alone celebrate it.

I don’t know what we owe our dead. I know it’s more than the reductive simplicity of we have always been here. I don’t know what it means to live that knowledge out loud, to make space in my life for the messes and triumphs of my ancestors. I don’t know where I belong, how I fit, what it means to be a queer woman in 2023, moved and broken open and challenged by these queer texts from 40, 60, 100 years ago. “But I can feel and I can write the word”—so that’s where I begin.

"I don’t know what we owe our dead. I know it’s more than the reductive simplicity of we have always been here. I don’t know what it means to live that knowledge out loud, to make space in my life for the messes and triumphs of my ancestors. I don’t know where I belong, how I fit, what it means to be a queer woman in 2023, moved and broken open and challenged by these queer texts from 40, 60, 100 years ago. “But I can feel and I can write the word”—so that’s where I begin."

Gorgeous, Laura.