Greetings, book and treat people! I’m writing this on election day. I voted this morning at the town hall in my little town, population 734. There weren’t any heated or contested races on the ballot, not even for my local school board. (So many local school board races are crucial this year, with all the book banning going on.) I’m not sure where we’ll be when you’re reading this except still here, still fighting.

In this week’s Bookish Teatime video, I talk about a few great books I’ve read this year that didn’t make their way into the newsletter. If you want to check it out, you can become a paying subscriber here. If you’re wondering what all this video nonsense is about, you can watch the first one here.

Some housekeeping:

I updated my Bookshop storefront with lots of new sparkles! You’ll find themed lists featuring books I love, including: The Best Queer Books You’ve Never Heard Of, Beloved Queer Books from Indie Presses, and Brilliant Short Books in Every Genre.

I’m still collecting reader questions. Anything bookish or bake-ish is fair game. The weirder the better! If you haven’t noticed, I could talk about books and baking all day. Send me your quandaries at queerbooksandbakes@gmail.com, or just hit reply.

This week’s books mess with, play with, wrestle with, reinvent, and tangle up reality. They all made me feel a little queasy, but not necessarily in a bad way—or, at least, in a bad way that means something has its hooks in you and is worth waking up for.

The Books

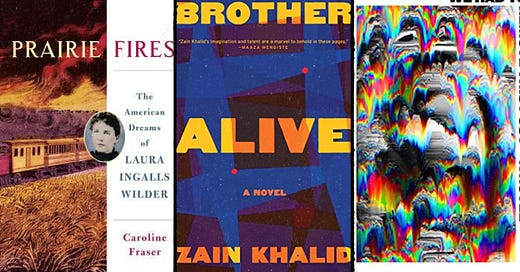

Backlist: Prairie Fires by Caroline Fraser (History/Biography, 2018)

This is a biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it’s also a history of the American West during the “pioneer” era in the late 19th century. Fraser brilliantly puts Wider in context, telling the stories behind the story Wilder told—stories of settler colonialism and entitlement, white conquest, stolen land, violence toward Indigenous people, and environmental degradation. It’s detailed and intimate—Fraser zooms in on the minutia of Wilder’s life—but it’s also expansive. Wilder’s is not a life story that exists in a vacuum. Fraser uses it as a lens through which to explore the thing that fuels so much of American culture, identity, and policy: myth-making.

Prairie Fires is about Wilder, for sure. But at heart it’s about the Little House books and how they came to be what they are. Much of the book is concerned with Wilder’s fraught personal and professional relationship with her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane. Lane and Wilder worked together on the Little House books for years, with Lane serving as editor, supporter, and behind-the-scenes orchestrator. Their ideas about the tone and substance of the books often clashed. Lane craved the kind of commercial success Wilder eventually achieved, and she strove to exert her influence on her mother’s literary estate. There’s so much fascinating history here about publishing, librarianship, editing, and artistic collaboration in the first half of the 20th century. The Little House books did not just happen. They were shaped and marketed and sold and presented in particular ways.

Fraser gets into all the contradictions between the world of the Little House books and the world Wilder actually lived in. There’s the rosy, happy, self-sufficient picture they paint of the perfect American pioneer family, of course. Everyone gets along, and while there might not always be enough to eat, nobody ever goes truly hungry, and they always have each other. The hardships the family faces in the book never feel dire or dangerous—there’s a romantic sheen to the whole series. I remember this vividly from when I read them as a kid. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to dislodge one particular scene from my mind, the one in Little House in the Big Woods where Wilder describes the attic fully stocked for winter: hanging cheese and preserved meats, squashes, barrels of flour and cornmeal, jars of preserves. I can’t say this is what made me want to become a farmer, but it certainly left a lasting impression.

But of course this is not how Wilder’s childhood actually was. Left out of the books is the extreme poverty; the toll of moving constantly; the endless debt, rootlessness, and uncertainty; and the realities of farm life with its nonstop physical labor.

Then there’s the image the books paint of the American pioneer as the classic American hero: good, kind, strong, independent, morally irreproachable. Indigenous people, when they appear in the books, are written in racist stereotypes. The violence settlers did to Indigenous nations is ignored or excused. The Wilder family arrives on the plains as if to a place that is wholly new and untouched, ready to be shaped to their whims and desires.

Fraser names all of these contradictions. She’s critical of Wilder, and of Lane, though she doesn’t portray either of them as monsters. She’s interested their humanity. I think a lot these days about the damage that books like the Little House series have done, and what we can do about it. Fraser’s approach is what I crave. We can’t ignore Wilder, or the incredible influence her work has had on American children’s literature. But we can talk about the context, and the nuance, and the details. We can look at the whole picture. We can look for patterns. We can name myth-making for what it is.

Frontlist #1: Brother Alive by Zain Khalid (Fiction)

Some books are easy to review, or, at least, they are easy for me to write about. Sometimes I finish a book and go right to my keyboard, impatient to give shape to my thoughts, the review practically writing itself. And then there are books like this, books so strange and alive and haunting that writing about them feels like the wrong approach. Brother Alive doesn’t feel like a book to write about, but one to talk about. It feels like part of a conversation.

What did I just read? What happened? I don’t know what to think about it. It made me feel a lot of things. It made me want to ask a lot of questions. It made me uneasy and curious and upset. I didn’t want to stop reading it. But as the story got stranger and slowly began to unhinge itself from an easily legible reality, this swirling, empty sadness lodged itself inside me. I was convinced the book was going to break my heart. It didn’t break my heart, exactly, though. Well, it did, but not in the usual way. I had to work so hard to untangle all the threads of plot, to decipher the rules of Khalid’s world, to find something to hang onto—some familiar shape, something solid and graspable. So the heartbreak became secondary to this intellectual puzzle. The first two thirds of the novel are built almost entirely out of emotion. The last third is all plot. It felt, at times, like three books smashed together. I’m still trying to parse all the connections and contradictions and dead-ends and through lines.

Are you wondering what it’s about? It’s about three brothers, raised by their adoptive father, Imam Salim, in an apartment above his Staten Island mosque. There’s a lot hidden family history, and a lot of secrets about the brothers’ childhoods in Saudi Arabia and Imam Salim’s past. It’s beautifully written and full of soft, unconditional love. There’s a lot of queer love, too. The characters are vivid. The narrator, Youssef, has this shadow he calls Brother, a shapeshifting being who follows him everywhere. Brother is a fascinating character, too. This is just the tip of the iceberg.

This book made me think about a lot of things—about how we’re seen and how we see ourselves; about perception and memory; about what it means to love through and despite and around mystery. Mostly, it made me think about the strangeness of constructing an identity. I think that’s what’s at the heart of this novel—all the choices we make to become ourselves, and the choices that are made for us, by parents, by family, by those we love, and how those choices, too, become us.

It’s not a soft book, or an easy book. It’s violent and viscerally, shockingly strange at times. I’d like to read it again because I understood maybe three layers out of a hundred, and I still have no idea what happened at the end. Khalid plays with reality, and interrogates the similarities between utopias and dystopias, and delves into religion and American politics, tells a story about greed and radicalization and justice and freedom and family. It’s dizzying. But for all that, as I think about what still lingers for me, what hit me the hardest—it’s all the love on these pages. There’s a truly astounding softness, a kind of joyful buoyancy, in how Khalid portrays the love that exists in this messy family. It’s remarkable.

Frontlist #2: We Had to Remove This Post by Hanna Bervoets, tr. by Emma Rault (Fiction)

I read this back in June and immediately wanted to review it and was immediately struck with the obvious problem: there is very little I can say about this book without ruining it. It’s not that there are twists or that it’s very plotty, although there’s some of that. It’s more that Bervoets builds the whole thing so deliciously subtly. It is so quiet. The book is structured as testimony. Kayleigh is talking to a lawyer, who wants her to sign on to a lawsuit against the social media platform she used to work for doing content moderation. So she tells him about the job, and about what happened, and about why she quit.

It works because you’re right there with Kayleigh, and you can’t quite see where it’s going, you’re changing as she changes, experiencing things as she recounts them, and then, wham, the book is over, and it’s hard to explain how you got to where you did except that you know exactly how you got there.

I love novels about the internet. I don’t think there are enough of them yet. The internet is so massive, so powerful, the influence it has on our lives so pervasive. And yet so many of us (and I’ve been guilty of this) insist on talking about real life and the internet as if they’re different. As if things that happen on the internet happen in some faraway place, some other plane of existence.

This is one of the best books about the internet I’ve read. It’s upsetting and disturbing. There’s quite a bit of graphic violence. It’s about radicalization and conformity and capitalism, about desensitization and loneliness, about the dangerous mix of reality and not-reality that the internet provides, about what it can conjure, what it can break. It is dark, and strange, and very real. I read it in one sitting, partly because I wanted to know what happened and partly because I wanted it to be over.

I thought a lot about The Subtweet by Vivek Shraya while reading this. It’s another brilliant book about the internet, although it’s not quite as dark. Both Shraya and Bervoets understand that the internet is, in fact, part of our physical world, and they write about it that way. Reading and writing fiction is one way to make sense of reality. And when it comes to untangling how the internet shapes and shifts and messes with reality, we’re just getting started, so I will be reading all the internet books I can get my hands on.

The Bake

Daylight savings time is over! Standard time is so much better! I’m not the only one who thinks so—and science even agrees with us! I celebrated on Sunday by baking the most Novembery of November desserts—buttery shortcrust, caramelized onions, apples, thyme, roasted squash. It was heavenly.

Savory November Tart

This isn’t so much a cohesive tart as a pile of fall vegetables inside a buttery crust. It doesn’t exactly hold together. Who cares? It’s lovely.

Ingredients

For the crust:

2 sticks (16 Tbs/227 grams) cold unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

240 grams (2 cups) all-purpose flour

pinch of salt

2-4 Tbs ice water

For the filling:

3 Tbs butter (or use olive oil)

2 medium onions, thinly sliced

1 delicata squash

2 Tbs cider syrup (or use 1 Tbs cider vinegar and 1 Tbs honey)

2 small apples

1 Tbs fresh thyme, chopped

juice from 1/2 lemon

grated Parmesan, to taste

Make the crust: Put some cold water in a bowl with ice and set aside. In a mixing bowl, combine the flour, salt, and butter with your fingertips. To keep the dough from getting too warm, dip your fingers in the ice water every now and then. Mix until it resembles coarse sand (some larger chunks of butter are okay). Add the water a little bit at time, mixing with your fingertips between each addition. When the dough mostly holds together, dump it on the counter and knead it a few times to gather into a ball. Flatten into a disk, wrap with plastic wrap, and stick it in the fridge. (You can do the mixing in a food processor.) (You also don’t have to chill it. This dough is so forgiving; I’ve rolled it out hundreds of times without chilling.)

Bake the crust: On a lightly floured surface, roll out the dough into a 12-14” circle. You want it to be fairly thin, but don't worry about it too much. Drape it over a 10” tart pan and gently mold the dough into shape, making sure to press gently into the creases along the edges. Trim the excess, but leave about an inch of overhang. Prick the bottom all over with a fork.

Butter the shiny side of a piece of aluminum foil and press it over the dough. Line with pie weights, dried beans, or rice. Bake at 400 for 30-35 minutes, until golden. Let cool completely on a wire rack. Trim the excess to create an even top.

Make the filling: Melt the butter in a skillet over medium heat. Add the sliced onions, a pinch of salt, and a grind of pepper, and cook on medium low, stirring often, until nicely caramelized, about 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, cut the delicata in half lengthwise and scoop out the seeds. Slice into 1/4-inch half circles. Arrange the slices on a baking tray and drizzle with the cider syrup, salt and pepper, and a splash of olive oil. Toss to make sure all the squash is coated. Roast at 400 until golden and crispy around the edges, 15-20 minutes.

Peel, core, and thinly slice the apples. Toss in a bowl with the thyme and lemon juice. Set aside.

Assemble the tart: Grate some Parmesan into the bottom of the cooled tart shell. Spread the caramelized onions on top. Arrange the apple slices in concentric circles on top of the onions. Drizzle some olive oil and any liquid left at the bottom of the apple bowl over the filling. Bake for 35 minutes at 400. Remove the tart from the oven, arrange the delicata slices on top, and grate some more Parmesan over everything. Bake another 5-10 minutes. Let cool to room temperature before serving.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Fall Rice Bowl with Roasted Butternut & Pork

I made this on a night I didn’t think I had the energy to cook, but I told myself I was just going to slice and roast a squash anyway. And once I’d done that, the rest happened almost without my even trying.

Cut a butternut in half. Peel and seed each half, and cut into small cubes. Toss with olive oil, salt, and pepper, and roast at 450 for about 20 minutes, until soft. Meanwhile, sauté an onion or two in some olive oil. Add a few minced garlic cloves and a handful of chopped fresh sage leaves. Add a pound of ground pork and keep cooking and stirring until the meat is cooked through. Add the roasted squash back into the pan, along with a splash of sherry vinegar and cider syrup if you have any. Serve over rice, topped with lots of grated cheese (cheddar, Parmesan, whatever you have).

The Beat: The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty, read by Tess Gunty, Scott Brick, Suzanne Toren, Kirby Heyborne, & Kyla Garcia

This is the last book on the NBA fiction longlist that I haven’t read. I started it over a month ago in print and managed to read about 20 pages. It was overdue at the library, so I gave up, and I’m trying it on audio. It’s definitely better this way. I’m more engaged. But still, for reasons I can’t explain, I’m weirdly resistant to it. I don’t want to like it. Is it because it feels like it should be queer and it isn’t? I don’t know. The writing is vivid, alive. So far it has the kind of strange, symphonic, complicated structure that I love—lots of POVs, intersecting stories. Still, if I hadn’t committed to this NBA project, I would DNF it. But I have six hours left—I may yet fall in love!

The Bookshelf

A Portal

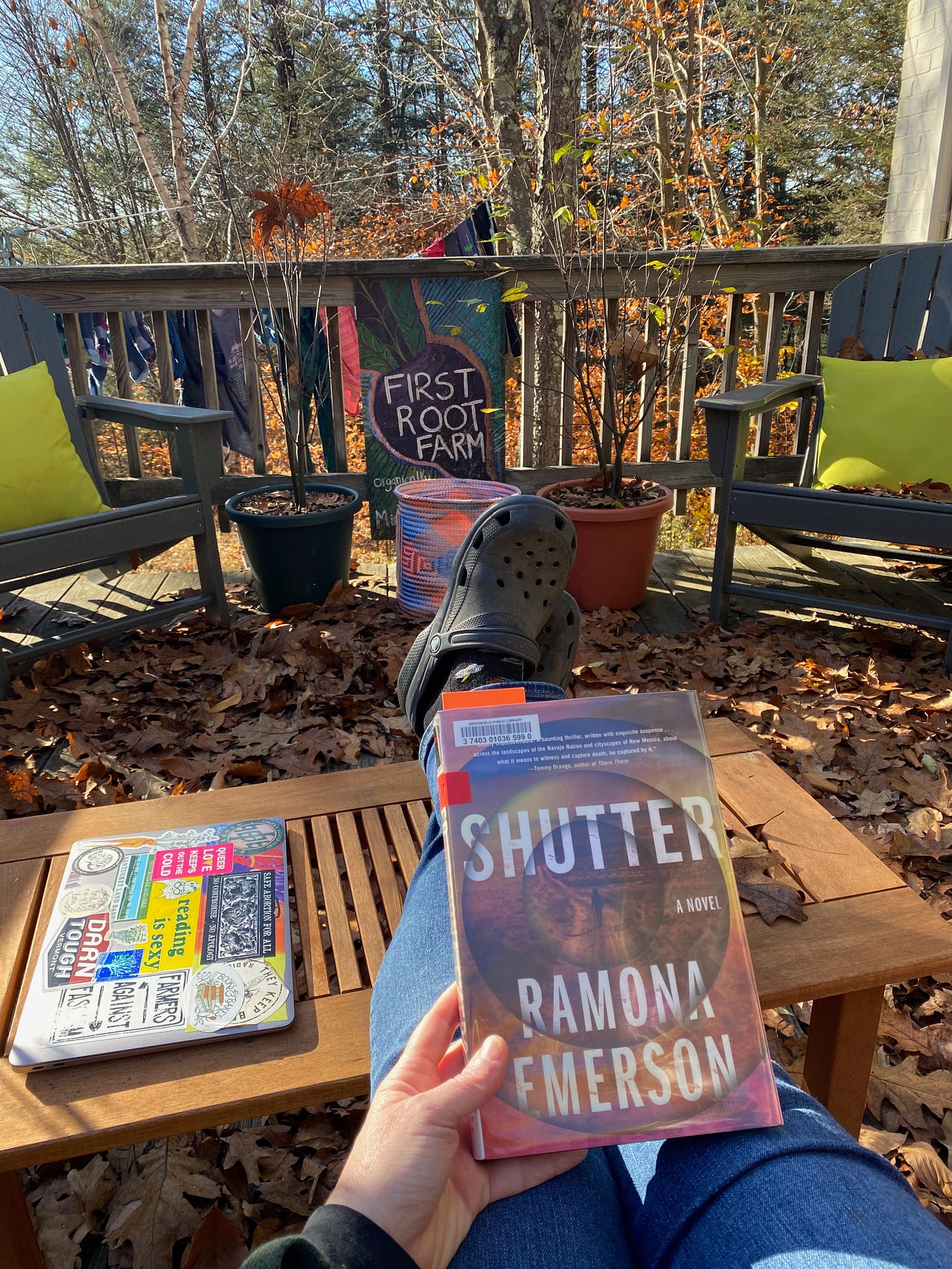

I finally finished Shutter by Ramona Emerson. It wasn’t for me. I don’t usually pick up crime novels and this one reminded me why. I’m not a plot-driven reader, and I don’t like violence and gore, but also: I find reading about crime boring. Is that weird to say? Everything in this book except Rita’s relationship with her grandmother was boring to me. I couldn’t make myself care.

I don’t regret reading it, because I like to keep an open mind, and, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, I still believe there’s a crime novel out there that I’ll love. This has me thinking: what makes you venture out of your wheelhouse to try a new genre? What makes it worth it to keep trying? Come talk to me in the comments!

A Baking Quandary

Today’s question comes from reader Emily, and it’s a great one!

How do you organize your ingredients? Especially if you store some stuff (like special flour) in the freezer?

She also mentioned how hard it can be to remember when you need more of something. This is especially true if you (like me) have amassed a small fleet of baking ingredients. I have been there, in the store, reaching for the brown sugar/buckwheat flour/vanilla extract/almonds before wrenching my hand back, because maybe I actually have another bag of that stashed away somewhere?

I keep more flours, kinds of nuts, and various sugars in my pantry than most people do. The two huge shelves under my kitchen island are devoted to baking ingredients, and they are sorted by type (a row of sugars, a row of whole flours, a row of sifted flours, a section for chocolate). My system is quite specific. So instead of explaining it, I’m going to tell you about the organizational principals I use. I hope they’ll be helpful even if you only have half a cupboard set aside for flour and sugar!

Buy in bulk: I started buying in bulk in earnest because of Cookie Extravaganza. I’m talking 50-pound bags of flour and 5-pound bags of almonds bulk. It’s cheaper, for starters. But even if there’s only a few things you use often enough to justify buying in bulk, it can make a big difference in pantry organization because: jars. Jars are everything.

Put everything in glass jars (or clear plastic containers): Storing everything in glass or plastic requires an initial investment, but it’s a worthwhile one. It’s much easier to sort and arrange ingredients if they’re all in jars! They take up less space than a random collection of boxes and bags that can’t be stacked! There’s provide pest protection (I’ve lived in a lot of houses with mice), and it’s much easier to pour/scoop ingredients out of a jar than out of a bag or a box. Visually, jars are extremely pleasing.

But here’s the best bit: you can tell at a glance how much you have left of any given ingredient. If a jar is low, I first check to see if I can refill it from my overflow (see below). If not, that ingredient goes on the shopping list. I use lots of different kinds and sizes of jars, too. I have huge glass jars for all-purpose flour and white sugar, and much smaller jars for nuts, dried fruit, speciality flours, the weird stuff I only use occasionally. I continually refill my quart-sized jar of almonds from the big bag in the freezer, and as soon as that bag is empty, I make a note.

Keep overflow ingredients in one place: I keep a huge plastic bin in the closet off my kitchen, and this is where most of the overflow goes—half-full bags of sugar, oats, dried fruit, cornmeal, baking powder, etc. The rest goes in the freezer (nuts, some flours, some spices). I don’t have a basement, and I have very limited storage space, but this system still works for me. Ingredients are spread out throughout my kitchen, but If I’m low on any of those ingredients, I know exactly where to look.

Of course, this system only works if you actually refill your jars as you bake, and actually remember to write brown sugar on the list when your five-pound bag is empty. I succeed at this about 75% of the time, which I think is pretty good.

Just for fun, a few of my favorite places to source bulk ingredients: Ground Up Grain (flour), Nuts.com (for real), and L'Epicerie (chocolate).

Around the Internet

Don’t want to read a whole NBA longlist, like I did? On Book Riot, I made a quiz that will tell you which book on the longlist you’ll actually love. I also made a list of must-read Indigenous authors.

Now Out / Can’t Wait!

Now Out

Conversations with Birds by Priyanka Kumar (Milkweed Press): A book of essays about birds and nature published by one of my favorite presses. I have an ARC of this sitting on my coffee table, staring at me mournfully. I can’t wait to read it.

Can’t Wait!

How Far the Light Reaches by Sabrina Imbler (December 6th, Little, Brown): It’s science week in the newsletter! I cannot wait to get my hands on this book of essays about queerness, family, and sea creatures.

Bonus Recs that Wrestle with Reality

If you like books that mess with you: Amatka by Karin Tidbeck and Skye Papers by Jamika Ajalon are two strange, surreal, interesting novels that play with the idea of what is real and what isn’t.

The Boost

I’ve seen this poem by Kyle Tran Myhre floating around a lot on social media. I know election day is over now, but there will be another. It’s worth reading, and so is Myhre’s commentary about it.

One of my favorite local indies, Roundabout Books, is raising funds to install an elevator in their new (old) building, to ensure that the whole store will be accessible. They received a matching grant from the state for the project. Roundabout is a wonderful bookstore and I am so excited about what their new space will bring to the community. If you’re able to donate a little, it would mean a lot to me.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Oh, the November light.

Catch you next week, bookish friends!

Shutter is waiting for me at the library this afternoon. I read a ton of mystery novels, which obviously often overlap with crime, but often crime is too dark or gruesome for me -- I find I just can't read books like that anymore. I'm going to give Shutter a try, though!

What makes me venture out of my wheelhouse to try a new genre are reviews/recommendations by people I trust or whose taste I know is similar to mine, whether I know them IRL or not -- if we usually like the same books and they enjoy a title that's out of my regular zone, I'll absolutely seek it out.

Coming back to this post to discuss The Rabbit Hutch. Did you finish it on audio?