Greetings, book-eaters and treat lovers! It’s been a while since I did a bird update. The feeder has been pretty quiet (lots of goldfinches, chickadees, nuthatches, and my favorite red-bellied woodpeckers). But the other day a huge bird flew past my office window, with a wingspan much bigger than any hawk I know. Maybe it was a Great Horned Owl? Or a Barred Owl? I tried to find it with my binocs but it vanished into the trees. Maybe, if I’m lucky, it’ll come back.

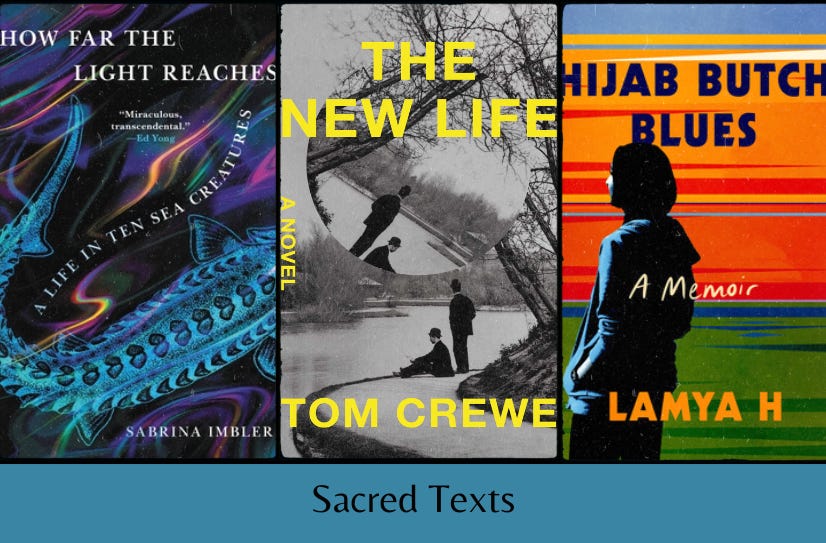

This week’s books are extraordinary; all three are already on my Best of 2023 List. The two essay collections, in particular, absolutely stunned me. They both reinvent queer memoir; they are both about curiosity and the world-opening possibilities of making queer connections. They feel spiritually connected. Reading them one after the other was a gift. I started thinking about the idea of sacred texts while listening to Hijab Butch Blues, and I was still thinking about it when I opened How Far the Light Reaches. How do you make a sacred text? What’s the alchemic process? What magic, what work, what mystery goes into it? What makes a thing sacred? Lamya H and Sabrina Imbler and the characters in The New Life are all grappling with these beautiful questions. So am I.

The Books

Hijab Butch Blues by Lamya H (Memoir, 2023)

Sometimes you read a book and it cracks you open and remakes the world. Sometimes you read a book and it weaves a new song along your skin, echoes a buzzing note in your tender throat, opens longings you’d set aside years ago, upends you.

Lamya H grew up in a South Asian family in an Arab country. She moved to the U.S. for college when she was 17. This memoir, shimmering and angry and gentle, full of loving questions and messy grappling, is not linear or straightforward. It’s not structured around the events of Lamya H’s life—her childhood, her time in college and graduate school, her first queer relationships. It’s structured around verses from the Quran. It’s a memoir about a sacred text that becomes its own kind of scared text.

Lamya H finds mirrors and doorways, solace and challenge, inspiration and strength in the Quran verses they write about. It’s breathtaking, the way they weave their own life into the fabric of this text that means so much to them, that guides their faith. They write about Yunus, swallowed by a whale, and find in this story a model of protection and self-love: sometimes stepping away from the world is the only way to enter it. Sometimes leaving isn’t failing. In Yunus’s whale they see a pathway toward queer refuge and rest, toward community care and thoughtful activism that is not rooted in visibility and loudness (western ideals of what queer lives should look like).

She writes about Yusuf, who is abandoned by his family, and she sees in his story her own abandonment, her grief, the patterns of familial trauma that spiral through a life, and she sees, too, how to begin untangling those threads, how to love and let herself be loved. She finds the divinity of transness in the fact that Allah is neither male nor female, and she sees her own story of queer awakening in Maryam, a woman who has never been, and does not want to be, touched by a man.

Their analysis of these Quran verses is so rich and clearsighted. Of course this is also a memoir, and so it’s about Lamya H’s life, too—finding a Muslim community in the U.S., dating in their twenties, falling in love, their choice not to come out to their family (this essay is especially powerful and brilliant), queer family and mentorship, activism and feminist politics, their experiences as an immigrant. This duality is what makes the book so good, because it’s not a duality at all. It’s wholeness. Lamya H does not section themself into pieces.

Part of this extraordinary wholeness is in the way she writes about queerness as canon. She isn’t reinterpreting Quran verses. She reads them truly. It’s natural. There is no reclamation. This is not a book of hidden stories made visible. She reads the Quran, and she sees herself in it, and even when it isn’t easy, even when it leads to confusion, she is still there, her whole self, inside the text, seen, held, challenged, whole. Queerness and transness are sacred, without qualification, without argument.

So much of this book is about faith as a framework for exploration. It’s about how you can find what you need in a sacred text if you listen to yourself. It’s about the study of sacred texts as a revolutionary praxis. At heart, I think, it’s a book of questions, and maybe that’s just another word for sacred text. The Quran that Lamya H studies and loves and wrestles with and discusses with their queer Muslim friends, that grounds them and surprises them and angers them—it’s not sacred simply because it’s the guiding text of Islam. They make it sacred. It changes them, and they change it, and in relationship, it becomes sacred. A sacred text is not a prescriptive book of ethics on how to live, but a praxis of questioning, of continual, daily opening.

I finished this book thinking about my Jewishness and my relationship to it, about what makes a sacred text, about how lonely it can feel to move through life without one and how scary and revelatory it might feel to open myself up to one. I don’t know where I’m going from here, but I am immeasurably grateful to Lamya H for this gift of a book.

The New Life by Tom Crewe (Historical fiction, 2023)

I have a soft spot for queer historical fiction, so I went into this expecting to like it, but I was not prepared for just how much I ended up loving it. It’s set in London in 1894. It’s about two men, John Addington and Henry Ellis, who, though they’ve never met, begin exchanging letters because they are academics who admire each other’s work. They soon decide to write a book together, Sexual Inversion, which will be a scientific study of homosexuality and an argument against Britain’s sodomy laws.

John and Henry are invested in this revolutionary project for different reasons. John is gay and married and desperate to change something his life. Henry is also married, though his marriage is a kind of social experiment. He and his wife Edith are part of a society of quasi-radicals intent on building the New Life. They do not live together; Edith has a lover. They want to do marriage differently, outside of patriarchal standards, but Henry, especially, doesn’t know how to do that. He only knows how to think about it.

For a while, John and Henry go along quietly, writing, exchanging letters, and living their messy, conflicted lives. But a few months before the book is to be published, Oscar Wilde is arrested, and his trial changes everything. It illuminates all the growing tensions between John and Henry, and exacerbates their wildly different perspectives about what, exactly, they are trying to do.

At heart, this is a book about activism. It’s about living in a state that actively wants you to disappear or die, and the tension between working for a better future and trying to live a life you can stand in the moment. The characters—John and Henry, their wives, John’s lover, their friends and colleagues—have different ideas about all of it: sacrifice, visibility, comfort, idealism. There’s a lot of emotional complexity and moral ambiguity. They are all trying, they are all hurting, they often make terrible, selfish choices, every one of which I felt in my bones.

It’s set in 1894 but it feels contemporary, because, horribly, we are still dealing with so many of the same things. Homosexuality is not illegal in the U.S., but the fascists are trying to make being trans illegal; they have already succeeded in banning gender- affirming care in some states. It’s unbearable, it’s terrifying, and it’s right now. I sobbed through huge chunks of this novel because it felt so close and relevant. Here we still are, trying to live our lives, trying to make change, fighting a fight that feels impossibly big.

This is also a novel about community care, about the reasons that people get into activism, and about what happens when intra-community conflict arises. John and Henry are connected by ideals and ideas. They respect each other but they’re not family. Everything starts to fall apart when they each realize that, while they may be fighting for the same thing, they are not doing it for the same reasons, and the emotional realities of those whys define each of their lives. Their relationship is a microcosm through which Crewe explores allyship and harm reduction and idealism and all the ways that identity and circumstance, especially class and status, intimately affect what we are able to do, what we are willing to do.

For John, the book is a kind of sacred text. He’s spent his life pretending to be someone he isn’t, he’s denied himself and denied himself and denied himself and he simply cannot anymore. So he pours himself into the project like it will save him. It becomes the only thing that matters, and he’s willing trample everyone in his path—his children, his lover Frank, Henry and his wife—to ensure its success. Frank is a working-class typesetter; the publication of the book and its potential fallout is going to affect him in ways it won’t affect John, but John can’t or won’t see this. He doesn’t care how many lives he has to ruin, including his own: he needs to be heard.

Henry’s relationship with his wife is also a kind of microcosm. He’s isn’t queer, or at least not in the obvious way that John is. He has a kink, something he doesn’t know how to talk about, and it’s partly his shame around this that compels him to write the book. Henry is good at thinking. He’s comfortable with theories. He wants to write about sex but he’s terrified of sex. He’s trying to live out this new kind of marriage, but he can’t talk to his wife about how he feels and what he wants. He knows how to put words on a page, and he wants those words to save him, but they can’t. The book only increases his awareness of the gulf between putting words on a page and living in a body. He can’t write himself away from his desires, his fears, his needs. For John the book is a declaration. For Henry, it’s an exploration. It scares them both in different ways.

At one point, John makes this impassioned speech about the book, which I found almost unbearable to read, because it’s a gorgeous monologue about justice and queer love, and yet it’s also self-destructive, almost vindictive. It’s so painful watching all of these conflicts play out in John’s character. Everything he wants is so understandable, but he’s also flawed and self-serving, and he lives, like us, in impossible times. It is difficult to make simple choices in impossible times.

Sexual Inversion is a real book from 1897. The characters are loosely based on the men who wrote it, and there’s an interesting author’s note where Crewe talks about the source material. The audiobook is phenomenal, and includes a conversation between Crewe and the narrator, Freddie Fox, which is also fascinating.

How Far the Light Reaches by Sabrina Imbler (Essays, 2022)

I don’t want to write a review of this book, I want to write a book about this book. I read it in one a long gulp, and even as I was reading, I was grieving, because I knew it was going to end sooner than I wanted it to. Sometimes you read a book and it settles inside you. Sometimes you read a book that feels as familiar as cold North Atlantic water on your skin, as beautifully distant as salty Pacific spray. Sometimes you read a book that feels like a piece of yourself returned to you, and like a jagged crag of coastline that will never quite fit. Sometimes the beauty of that closeness and that dissonance blends into something entirely new. How do I distill all of that into something paragraph-shaped?

Here are essays about the ocean and about queerness and about Imbler’s family and relationships, their loves, the cities they’ve called home, their cultural heritage, their gender. Here, in these incandescent essays that are a hundred shades of blue and green, Imbler explores the ocean as a sacred text.

Like the sacred queerness Lamya H finds in the Quran, the queerness Imbler finds in the ocean is natural, obvious, instinctual. There is nothing rote or forced about it. Imbler doesn’t turn to nature in search of themself; they turn to nature because they know they are already a part of it. They make connections between the communities of organisms that thrive around hydrothermal vents and queer dance clubs, between immortal jellyfish and queer time, between the ways cuttlefish morph and the infinite dance of being trans. But these connections are not a quest for proof. They exist because they exist. Imbler writes about science through a queer lens because it’s their lens. Like Lamya H, they resist compartmentalization. They insist on wholeness.

Their love for these ocean creatures, their weird and miraculous evolutions, their mysterious adaptations, their creative survival—crashes like the surf through every essay. So does their queerness, their transness, their mixed-race identify. It’s all innate. The essays aren’t especially inventive, structurally—each one is a woven braid of memoir and science—and yet reading them, I experienced a kind of intense attention that felt new. There is something both daring and healing in Imbler’s riotous mix of paragraphs, paragraphs about whale falls and sturgeons, sand strikers and queer sex, motherhood, octopuses, and gender euphoria, butterflyfish and sexual assault, Riis Beach and immortal jellyfish, strap-ons and necropsy and dance clubs and goldfish.

The straight world is so hungry to tear apart queer and trans people, especially queer and trans people of color. It wants to analyze and pin. It wants us to section ourselves off, to be one thing at a time, to perform queerness in this particular way, but only in this one place, and only for these people, and only if we’re absolutely sure and we’ll never, ever change our minds. This book is Imbler refusing.

I would have happily read 50 more queer essays about sea creatures. Every single one broke me open, made me want to rush to the page with my own pen. I sobbed when I finished, and returning it to the library felt like giving away a piece of myself. I had to calm myself down by immediately adding it to my to-buy-at-the-end-of-the-year wishlist on Bookshop. I am already planning my reread.

In a gorgeous essay about mixed-race identity, Imbler writes this extraordinary sentence: “I am not interested in writing toward some resolution of belonging.” I read it four or five times before I could move on to the rest of the paragraph. Imbler and I have different experiences of queerness, and yet this sentence spoke to the deepest, softest parts of me. They go on to say, “I do not want to feel resolved about myself.”

I do not want to feel resolved about myself or my writing. I do not want to resolve the mysteries that live inside my chest. I want, I think, to write toward, through, and into sacred text—be it the ocean, or the Torah, or How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, which I am currently rereading, or the ridge behind my house. I don’t know yet what my sacred texts are. I don’t know what they feel like in my hands. How Far the Light Reaches, for me, is a queer opening into possibility, a light guiding my way into the depths.

The Bake

This recipe is from Snacking Cakes, which may not be a sacred text, but it is currently my most beloved cookbook. I didn’t do much to it beyond add some chocolate and top it with a luscious dulce de leche frosting. If you use all frosting on the cake, like I did, you will get a very thick layer (yum). If you aren’t into that, save about a quarter of the recipe for another project.

Sesame Cake with Dulce De Leche Icing

This is the best cake I’ve made in a while. No notes.

Ingredients:

For the cake:

6 Tbs (50 g) sesame seeds

150 grams (3/4 cup) sugar

1 egg

1/2 cup (120 ml) milk

1/2 cup (120 ml) tahini

1/4 cup (60 ml) neutral oil, i.e. sunflower or canola

1 tsp vanilla

3/4 tsp salt

160 grams (1 1/4 cups) all purpose-flour

1 1/2 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp baking soda

85 grams (1/2 cup) chopped chocolate

For the icing:

1 stick (113 grams) unsalted butter, at room temperature

180 grams (1 1/2 cups) powdered sugar

3/4 cup dulce de leche

1 Tbs milk

1 tsp vanilla

Preheat the oven to 350. Butter a 9” round cake pan and line it with parchment paper. Butter the parchment paper. Sprinkle about half the sesame seeds all over the bottom and sides of the pan. Set aside.

In a large mixing bowl, combine the sugar and egg and whisk until pale and thick, 1-2 minutes. Add the milk, tahini, oil, vanilla, and salt, and whisk again until smooth.

Add the flour, remaining sesame seeds, baking power, and baking soda. Mix to combine. Fold in the chocolate and mix until smooth.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan. Bake for 25-30 minutes until a tester inserted in the middle comes out clean. Let cool completely in the pan on a rack before gently turning it out .

To make the icing: In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, or using handheld beaters, cream the butter and sugar until smooth, about 2 minutes. Add the dulce, milk, and vanilla and continue beating until frosting is thick and smooth, about 3 minutes more. If it’s too thick, add a little more milk. If it’s too thin, add a little more powdered sugar.

Spread the frosting over the cooled cake and sprinkle with more sesame seeds. It’ll keep for a week or so.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: White Bean & Lamb Stew with Saffron

My bean cooking adventures continue! I made a big pot of white beans last weekend, and this is the first thing I did with them. It’s a hearty winter stew brightened with saffron and lemon. I almost never use saffron, but I happened to have some! It’s delicious, but this will still be good without it.

Heat some butter or olive in a large pot or Dutch oven. Sauté two sliced onions. Add a pinch of saffron, some paprika and oregano, a bit of Aleppo, and a good dash salt. Cook on low heat, stirring to distribute the spices, until the onions are soft. Add a pound of ground lamb, 4 cups of stock (any kind!), 4-6 chopped potatoes, and a jar of canned tomatoes with their juices. I like to snip the tomatoes into smaller pieces with kitchen scissors, but you can also chop them. Purée 4 cups of cooked white beans with an immersion blender or food processor, and add the puree to the pot. Let everything cook on medium-low heat, just bubbling, until the potatoes are soft, about 35 minutes. Add the zest and juice of 2 lemons and a big handful of chopped parsley.

The Beat: VenCo by Cherie Dimaline, read by Michelle St. John

I’ve been struggling to read sci-fi and fantasy since 2020, but something clicked in my brain recently and I devoured two fun SFF audiobooks last week: Ocean’s Echo and A Marvellous Light. I got so excited that I decided to pick this up, which may have been a mistake, because apparently the only kind of SFF I can handle at the moment is what I’m calling “sexy vibes with magic and/or space.” This is a contemporary fantasy about an Indigenous woman who accidentally tumbles into a coven. It’s very good, with lots of queer and trans characters and cool dream magic. But it is not romantic or fluffy, so my brain is struggling. If you’re into witchy fantasy, I recommend it!

The Bookshelf

A Portal

I started using Storygraph this year for reading challenges. I don’t like the interface at all for actually tracking my reading, but I’m really enjoying using it for this purpose only! Reading challenges are fun for me because I love checklists and I feel absolutely no pressure whatsoever to finish any of them. These are six of the challenges I’m doing this year, and I get a little jolt of joy every time I add a book to one of them.

Come talk to me about reading challenges in the comments and/or be my friend on Storygraph if you’re there!

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I made a list of some essential Black queer history books. For Audiofile, I wrote about some audiobooks I loved where small rebellions lead to big changes.

Now Out / Can’t Wait!

Now Out

On A Woman’s Madness by Astrid Roemer, tr. Lucy Scott: This queer novel about a Black lesbian in Suriname was first published in 1982, and has just been translated into English! I don’t even care what it’s about, it hits on so many of my interests.

Can’t Wait!

Saving Time by Jenny Odell (Random House, 3/7): I liked Odell’s first book, How to Do Nothing, so I’m intrigued by this one, an exploration of the clock, capitalism, and our relationship to time.

Dispatches from Puerto Nowhere by Robert Lopez (Two Dollar Radio, 3/14): I’m a big fan of Two Dollar Radio, and this memoir about family and immigration sounds great.

Queer Your Year

News & Announcements: It’s time for the February raffle!

I had a blast sending out the January prize packs! If you submitted a game card but didn’t receive an envelope, it’s probably because you hadn’t read books for any of the winning prompts. Here’s the info on the February raffle:

This month’s prize is an incredible queer book bundle from Metonymy Press!

While only one person will win the book bundle, anyone who has completed any of the winning prompts will receive a prize pack! If you received a prize pack in January, you aren’t eligible to for another one, but you can still enter the raffle. Prize packs ship worldwide. Please remember to enter your complete mailing address on the form.

If you haven’t already downloaded your game card, you can do so here. This is also where you’ll find the link to submit your game card. Further details are here.

You have until February 28th to submit your game cards.

And now, the winning prompts! They are: 5, 13, 18, 20, 22, 24, 35 and 38.

Recs!

Prompt 11: A nonfiction book about queer parenting

I am not a parent, and yet I love books about queer parenting more than almost any other kind of nonfiction. I gobble them up. I even wrote an essay about it. I loved Krys Malcom Belc’s genre-blending memoir about trans parenting; Francesca T. Royster’s gorgeous memoir about adoption, partnership, and the connections between queer and Black families; Maggie Nelson’s classic text on queer pregnancy and motherhood; and Julietta Singh’s lyrical book-length essay about queer familial architecture and parenting at the end of the world.

I also enjoyed Waiting in the Wings by Cherríe Moraga and Like a Boy But Not a Boy by Andrea Bennet, though I haven’t reviewed them. Knocking Myself Up by Michelle Tea is at the top of my TBR.

Prompt 13: A book with less than 100 ratings on Goodreads

Under the radar queer books are one of my literary loves, so here are a few I adore:

If you love well-edited essay anthologies: Between Certain Death and a Possible Future by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

If you love weird plays that make you feel seen: How to Fail as a Popstar by Vivek Shraya

If you love an intellectual challenge: Double Melancholy by C.E. Gatchalian

If you love short stories with a strong sense of place: Spell Heaven by Toni Mirosevich

If tyou love experimental nonfiction: Madder by Marco Wilkinson

The Boost

I’ve loved doing book giveaways for a cause (details about it here if you’re new), but it’s been very quiet the last two weeks, and it takes a lot of organization on my end to set up. I hope to continue with it, but I’m reassessing the best way to do so. Maybe I’ll do occasional newsletters dedicated entirely to giveaways. In the meantime, here are some links for you:

Sword & Kettle Press is crowdsourcing funding for a mini chapbook series, New Cosmologies. I don’t know much about this press, but it sounds super cool to me!

I’ve only just started this article, “Against Queer Presentism: How the Book World Neglects the Archive”, but it is something that has been on my mind.

This is a beautiful review of one of my favorite books of 2023 so far, I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself.

A virtual abolitionist book club!

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I’ve been reveling in the late afternoon light in my office recently.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! Next week’s essay might be the one I didn’t write last week about At the Pond, or it might be about sacred texts and my relationship to Judaism, or it might be something completely different. If you want to read it, you can subscribe here.

I'm glad I'm not the only one who loves the reading challenges feature on Storygraph! I always have waaay more going than is functionally possible to complete, but I love planning for them so much. I find them really helpful when I can't figure out what to read and need to narrow down my options. I wish I was like you and didn't pressure myself about them, but sometimes that happens to me. I've made a couple Book Riot suggestion lists into reading challenges, and that's fun. Now that I see which ones you're doing, I'm going to have to be nosy and see which ones I want to join too! lol