Greetings, bookish humans! I finally have some bird updates for you. For those of you who are new here, I often used to open this newsletter with tidbits about the birds I saw around my yard. Then I moved into the woods and encountered a bear visitor snacking on my birdseed. So my feeder is a no-go until winter.

There are still lots of birds around, though! Last week, working in my new office (it’s finally set up!) I watched what I think was a pair of wood thrushes in the tree outside my window. It was hard to get a good look at them, so I can’t be sure, but hopefully they’ll be back, because, whatever they were, they were gorgeous.

This week’s theme is one close to my heart: queer elders. I’m not sure I can put into words how much it has meant to me to have queer elders in my life. For so many queer people, throughout history and still today, even knowing queer elders, let alone having relationships with them, has not been a given. So when I encounter queer elders in books I want to do a little dance and then shove those books into the hands of every young queer person I know.

I was so moved by Kumiko, the queer elder in Shadow Life, that I wrote a piece for Book Riot about the power of seeing queer elders in books:

Seeing queer elders come alive on the page, imperfect and full of regret, still struggling, still afraid of death, still falling in love, dealing with pills and back pain and a world that wants to kill or erase them, watching these funny, weird, loving, messy elders have sex and fight monsters and bask in the luxurious pleasure of a cup of tea — it creates a portal into a queer future, and gives me space to imagine myself there.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about Roxane Gay’s recent essay on queer elders, which definitely made me cry.

The Books

Backlist: The Marrow Thieves by Cherrie Dimaline (YA Dystopian Fiction, 2017)

This YA dystopia is set in a brutal and bleak future. The world has been ravaged by climate change, which is bad enough. But on top of that, most people in North America have lost the ability to dream. This loss leads to widespread chaos—it turns out that not being able to dream causes people to lose track of themselves, dissociate from reality, and turn violent. The only people who can still dream are the Indigenous peoples of the continent, whose bone marrow contains something that holds the cure for those who can no longer dream. The rest of the world wants it. White settlers are hunting Indigenous peoples, capturing them, and holding them in facilities that are a terrifying, future version of residential schools. In order to survive, most Indigenous people have gone into hiding.

That all sounds horrifying and grim. It is. But though this book deals with explicit trauma, violent racism, the legacies of colonial violence against Native people in North America, and a terrifying future, it is not all bleak. The story follows Frenchie, an Indigenous teenager who gets separated from his family after “recruiters” come looking for them. He joins up with a group of other Indigenous people from various Nations and of various ages, all traveling together trying to stay alive. The group includes several elders, including Miggs, who is gay, and who becomes a father to Frenchie and the other teenagers and kids in their group.

It’s hard to describe how Dimaline manages to write such a hopeful story, full of connection, love, and cultural celebration in a world that is so devastating. There is tragedy in this novel. It’s not a light book, and I don’t want to pass it off as one. But at heart, it’s not an adventure story, and it’s not even really about resistance and fighting injustice (though that’s certainly part of it). It’s a book about a family that forms in the face of unbelievable cruelty. It’s about the relationships between Frenchie and the people he comes to love. It’s about intergenerational knowledge.

I was completely surprised by the ending. I don’t want to give anything away, because I think it’s masterful, but I will say that it shifted the tone of the whole book for me. So often, books like this rely heavily on tragedy. Many dystopias center despair and don’t make any room for the possibilities that come with joy. Dimaline doesn’t do that. It’s almost like she’s not interested in telling a story about Indigenous pain, or about violence, though, on the surface, the book is about both those things. But as the ending nears, and then slowly unfolds, it becomes clear that there’s a softer, more tender story buried in this book, one about queer family and biological family, first love, and ancestral power.

In a lot of ways, this novel reminded me of Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice. One of the things I love most about Moon of the Crusted Snow is its glacial pace. It’s a post-apocalyptic novel that reads like a thoughtful character study. This novel is like that, too. There’s some action, and a looming sense of danger, and there’s certainly tension, but it’s not fast-paced. It mostly consists of the characters thinking and talking and sharing stories. The stories sometimes go on for a long time. There’s also a lot of Frenchie’s inner emotional life, as he works out his feelings in his head. It doesn’t unfold the way a lot of readers expect dystopias like this to unfold. That refusal to adhere to expected norms is one of the book’s biggest strengths.

If you’re wondering why I’ve included this novel in a roundup of books about queer elders, you’ll just have to read it for yourself. Miggs, a queer elder and the leader of Frenchie’s group, is such a beautifully drawn and interesting character. His queerness is integral to who he is, and his backstory with his husband Isaac is a major plot point. But his Indigenous identity is equally important; his queerness is not front and center. There’s almost no homophobia, which is a relief, though there is some queer suffering. I was continually surprised by Miggs’s story. I kept thinking I knew where it was going, and then Dimaline would take it in an unexpected direction. Even though this novel is told from the perspective of a teenage boy, it’s a book that centers elders. Miggs and the group’s other elder, Minerva, carry the heart of the story. It’s such a joy to encounter queer elders in a book like this, one that isn’t specifically queer, but that honors queer lives and queer stories.

Frontlist: Shadow Life by Hiromi Goto and Ann Xu (Graphic Fiction)

Friends, I just want to shout incoherently about how much I love this book. Kumiko isn't technically a grandma, so I can't say she's my favorite grandma in fiction, but I can say she is now my favorite elderly woman in fiction. Literature could use a few more no-nonsense, truth-talking, outrageously funny bisexual elders. Seventy-six year old Kumiko is all of that and more. She knows what she wants and gives no fucks about what anyone else thinks about it. She refuses to deal with bullshit, especially from her adult daughters. She cracks herself up while walking around the city doing errands. She has a sharp sense of humor and she’s super observant. She’s also grumpy and silly and stubborn. I adore everything about her and would like to read 100 more novels staring her.

Let me back up. Brought to life by Ann Xu’s simple and strikingly honest illustrations, this joyful novel is a fantastical, belly-laugh-inducing romp through the challenges—and unexpected joys—of getting old.

When Kumiko’s adult daughters put her in an assisted living community, she immediately misses the independence of her old life. Taking matters into her own hands, she breaks out and finds herself a charming apartment in the heart of the city. Xu’s art gorgeously captures the simple pleasures of Kumiko’s new life: preparing dinner, swimming laps at the local pool, enjoying a cup of tea.

But Kumiko’s peace is shattered when Death’s comes calling. She is most definitely not ready to die, so she traps Death in a vacuum cleaner. As you do. But it’ll take more than that to defeat Death for good, and Kumiko has to draw on her own inner strength, along with the help of several new friends and her elderly ex. Throughout, she navigates the increasingly agitated attention of her daughters, who say they want what’s best for her, but never ask her what that is.

Goto’s thoughtful dialogue and Xu’s exuberant drawings combine to create an absolutely unforgettable character. The care Xu takes to draw Kumiko’s aging body is especially moving. She celebrates all of Kumiko’s wrinkles and folds, her creaky joints and aching muscles. What a joy it is to see the specificity of an old woman’s life experiences inked so tenderly onto the page. There are a bunch of scenes where she's naked, doing normal life stuff, like changing clothes or taking a shower, and it made me realize how much I love seeing older bodies depicted with so much honesty and nuance.

There’s also this really beautiful plot involving Kumiko’s ex, a woman she was in love with before she got married. They reconnect in the midst of Kumiko’s battle with Death, and it’s poignant and tender and feels so true to queer life. This is someone Kumiko hasn’t been in touch with in a long time, and yet they are family to each other in a very specific way. Throughout the book, Goto continually portrays Kumiko’s queerness so thoughtfully. Sometimes it matters a lot and sometimes it doesn’t. It depends on who she’s talking to, the situation, her mood. I still haven’t found the perfect word for this kind of story, where queerness is A Thing and also Not A Thing, but I love it whenever I encounter it, and Goto nails it here.

Shadow Life is a fast-paced adventure brimming over with quiet magic and made all the more powerful by its realism. Goto delves into the complexity of adult child-parent relationships, the nuances of caregiving, and the vulnerability, at any age, of opening oneself up to true intimacy. It’s a poignant story about a woman seeking autonomy in a world that routinely renders elderly women—especially elderly queer women of color—invisible. Kumiko’s refusal to allow anyone to silence her, including Death himself, is a welcome relief in a literary landscape that rarely gives LGBTQ+ characters over fifty any voice at all.

Upcoming: Between Certain Death and a Possible Future edited by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore (Essays, Arsenal Pulp Press, 10/5)

This book isn’t so much about queer elders as it is about the idea of elders, about elderhood (is that a word?), and about how elders, in their presence and their absence, have shaped queer culture and queer history. It’s a collection of essays by queer writers about growing up and coming of age with the AIDS crisis. The contributors are not people who lived through the worst years of the AIDS crisis as adults, but as children and teenagers. They’re of my generation—people mostly in their 30s and 40s, most of whom were born in the late 1970s through the early 1990s. It’s not so much a book about queer survival as it is about the legacy of queer history. It’s about the generational trauma that lives in the body and the devastating impact of growing up with the understanding that desire, queerness, and death were inexorably linked. It’s also about the power of telling stories and the legacies of community care, resistance, and activism that grew out of the AIDS epidemic.

In her introduction, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore explains the generational frame for the anthology like this:

Usually we hear about two generations—the first coming of age in the era of gay liberation, and then watching entire circles of friends die of a mysterious illness as the government did nothing to intervene. And now we hear about younger people growing up in an era offering effective treatment and prevention, and unable to comprehend the magnitude of the loss. We are told that these two generations cannot possibly understand one another and thus remain alienated from both the past and the future. But there is another generation between these two—one that came of age in the midst of the epidemic with the belief that desire intrinsically led to death, internalizing this trauma as part of becoming queer.

By telling this specific generation story in all its complications, how do we explore the trauma the AIDS crisis continues to enact and imagine a way out? Could this offer a bridge between the other two generations?

What follows is a heartbreaking, fierce, and beautiful book. There are far two many incredible essays to touch on all of them. The contributors are fairly diverse; many are gay men, but there are also essays by queer women and nonbinary people. There are quite a few by trans people of various genders. Most focus on the US and Canada, but there are several about growing up elsewhere during the AIDS crisis—Egypt, Colombia, Panama.

There’s a wonderful range in terms of subject matter. Some essays are about losing friends or getting an HIV diagnosis. Other explore the complexities of PrEP, condom use, and safe sex practices. Some touch on sex work, houselessness, familial homophobia, and how intersections of race, class, and gender shape people’s experiences of HIV. So many of the essays are about fear and shame and what it felt like to grow up in places (cities, rural areas, small towns, etc.) where the media and society in general linked queer sex and desire with death. There are essays about falling in love, and activism, and exhaustion, and burnout, and HIV-related stigma, and navigating intimacy.

Throughout the whole book, there’s a sense of both continuity and loss that’s hard to put into words. In “To Say Goodbye” Andrew R. Spieldenner writes: “We are a generation of witnesses, and this weight shapes how we love, how we fight, and how we break away.” In “Leaving Atlanta”, Stephen H. Moore writes about his uncle’s death from AIDS and his later coming of age as a trans adult. He recounts a conversation with a new lover, a trans man a few years younger than him, who tells him he doesn’t know any queer men who survived the plague years. So Moore takes this new lover to visit with one of his friends:

They carry on a polite and friendly conversation, and my boy walks out into the sun smiling, a little more secure in his gender. For the first time, I feel like maybe the plague hasn’t taken everything from us, like maybe there’s a future where we all will know queers our parents’ age who are as fearlessly, joyously sexual as we want to be.

In “Looking for Gaëtan”, Ryan Conrad writes about how searching for missing queer elders, and seeking to understand queer history, have shaped his identity as an artist. Playwright Dan Fishback’s beautiful essay “Jason & David” about art and AIDS and coming of age as a gay teenager in the 90s, includes this startling line: “Like nearly all displaced peoples, we dream in a language we don’t speak.” It’s in reference to a Yiddish phrase, lakhn mis yashtsherkes which means literally “laughing with lizards” and describes the state of laughing and crying at the same time.

There is so much loss in these pages. It’s sometimes hard to take. The honesty and vulnerability with which these writers share their stories is both devastating and liberating. But there’s also a sense of movement, a beautiful tapestry of connection between past, present, and future. These essays mourn the queer elders we lost, and the ones who never got to get old. They’re about the the elasticity of what it means to be a queer elder, about how time sometimes moves differently for queer people, and how, especially at the height of the epidemic, queer elders were often not elders at all, but young people taking on that role. But there is also a celebration in these pages, a recognition of the sacredness of cross-generational queer conversations.

This book is about what happened and about what is happening. To me, it feels like a bridge. Maybe that’s what Sycamore set out to build. I hope so. I know I’ll be thinking about it for a long time to come. It’s out on October 5th and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

This recipe comes to me from a beloved queer elder, my aunt Liz. I keep it in my recipe folder, a photocopy of a page from a cookbook, with the original author’s name, Susan Hermann Loomis, in my aunt’s handwriting. When I make it, I often think about recipes and lineage. This is not my aunt’s recipe, but I associate it with her, because she was the one who introduced me to it, who made it many times for family gatherings, and then gave me the recipe when I asked for it.

It’s a reminder of what I love about recipes—they don’t truly belong to any one person. Often, they come to us sideways, altered, layered with stories. Queer lineage is like that, too. It’s rarely a straightforward decent, grandparent to parent to child. Most often, it’s a lot more spacious.

This is a beautiful, simple tart, elegant and delicious. I make it every fall, and think of my aunt, grateful for my presence in my life. I wonder who I’ll pass it on to, and what it will mean to them.

Apple and Thyme Tart

From On Rue Tatin by Susan Hermann Loomis

The vanilla sugar really makes a difference in this recipe. It’s super easy to make, but it does take some time. In an airtight container, combine 400 grams (2 cups) granulated sugar and the scraped seeds of one vanilla bean. Mix the seeds into the sugar with your fingers, then bury the scraped bean in the sugar. Let sit for 1-2 weeks before using. It’ll keep indefinitely. You can also buy it!

Ingredients:

For the pastry:

200 grams (1 1/2 cups) all purpose-flour

Pinch of salt

7 Tbs (105 grams) unsalted butter, chilled and cubed

4-6 Tbs ice water

1 egg

For the filling:

6 tart apples, cored, peeled, and thinly sliced (about 1/4” slices)

100 grams (1/2 cup) vanilla sugar

1 Tbs fresh thyme leaves

To make the pastry: Combine the flour and salt in a food processor and pulse to mix. Add the cubed butter and process until the mixture resembles coarse meal. With the machine running, add the water a little bit at a time, just until the dough starts to come together. Turn it out onto a floured surface, knead it a few times to gather it into a ball, and let sit, covered at room temperature, for about an hour. (You can also mix the dough by hand.)

To assemble and bake: Preheat the oven to 425. Whisk the egg with a teaspoon of water to make an egg wash.

On a lightly floured surface, roll out the pastry into a roughly 14” circle. Transfer it to a 9” removable-bottom tart pan. The edges of the pastry should overlap evenly all around. You can gently press the sides against the edges of the pan, but don’t trim the edges.

Layer half the apple slices into the pastry and sprinkle half the sugar and all of the thyme leaves over them. Top with the remaining apples and the remaining sugar. Fold the edges of the pastry up and in over the apples, like you’re making a galette. The pastry won’t cover all the apples—you want an open space in the middle.

Brush the pastry with the egg wash. Place the tart pan on a baking sheet. Bake until the crust is golden brown and the apples are soft and juicy, about 50 minutes.

Allow to cool slightly before removing the sides of the pan. It’s delicious warm or at room temperature.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Lamb Chops with Dates, Feta, Fennel & Tahini Garlic Sauce

This is based on a Melissa Clark recipe from the NYT cooking app, but I didn't have a lot of the ingredients she called for, so I took it in my own direction. It’s one of those recipes that looks a lot fancier than it actually is. It comes together quickly and it is so delicious. It’s rare that I cook such a decadent meal like this for myself. I savored every bite. And if you don’t eat meat, the salad part of this is divine and totally worth your time even without the lamb chops.

You’ll need some lamb chops. I used a combo of loin and shoulder chops, about two pounds, though the original recipe calls for rib chops. In a 9x13 baking dish, combine ~1/4 olive oil, 3-4 pressed garlic cloves, some crushed cumin seeds (1 Tbs or so), a few sprinkles of Aleppo pepper (I’m out, but it would have been great), and the juice of half a lemon. Place the chops in the marinade and toss to coat. Sprinkle some fresh thyme sprigs over the top. Cover and let sit in the fridge for at least 20 minutes.

Make the salad: Thinly slice a bulb of fennel. Pit and quarter 6-8 dates. Slice a few scallions. Chop up a big handful of fresh mint and a big handful of parsley. Dill would be great, too (I didn’t have any). Toss it all in a big bowl. Add a few sliced cherry tomatoes. (I thought this might we weird with the dates; I was super wrong.) Crumble in some feta, a big block. Drizzle some olive on top, along with a few splashes of white wine vinegar and salt and pepper to taste. Toss well.

Make the sauce: Whisk together ~1/4 cup olive oil, the juice of half a lemon, 3ish Tbs tahini, and 2 pressed garlic cloves. Add a few tablespoons water until the sauce is lovely and smooth.

Cook the chops: Heat a cast-iron or similarly heavy pan until it is quite hot. Arrange the chops in it. The recipe said to cook them for 2 minutes on each side. I cooked the small ones for about 5 minutes on each side and the bigger ones for 6-8, and my chops were tender and nicely pink. So who knows. Maybe rib chops are thinner? You’re on your own with the cooking time.

Pile some salad onto plates along with a chop. Drizzle the sauce over everything. Sprinkle with sumac. I promise this meal is quicker than all these paragraphs make it seem! I also promise it’s more delicious than my only-adequate picture makes it look.

The Beat: Big Girl, Small Town by Michelle Gallen, read by Nicola Coughlan

I’m almost done with this and it’s such a unique listen. There is almost no plot. Instead, we spend a week or so with the narrator, an Irish woman named Majella who lives with her alcoholic mother and works at the local chip shop. The book is full of her likes and dislikes and sharp observations, both of herself and the people around her. There’s something almost meditative about it, though much of Majella’s life is rather bleak. It’s a close-up book, a look-at-this-person’s-life book. I’m becoming more and more fond of them. There’s such pleasure in simply experiencing a character’s world without the expectation of anything happening. And Nicola Coughlan’s narration is amazing. It’s one of those audiobooks it’s hard to imagine reading in print because her voice is so perfect.

The Bookshelf

The Library Shelf

I’ve read 18 books of poetry this month for The Sealy Challenge! But you wouldn’t know it looking at my library shelf, which currently holds 38 books of poetry. And I’ve got nine more ready to be picked up. Friends, I am reveling in poetry, and I am not going to stop when August ends.

The Visual

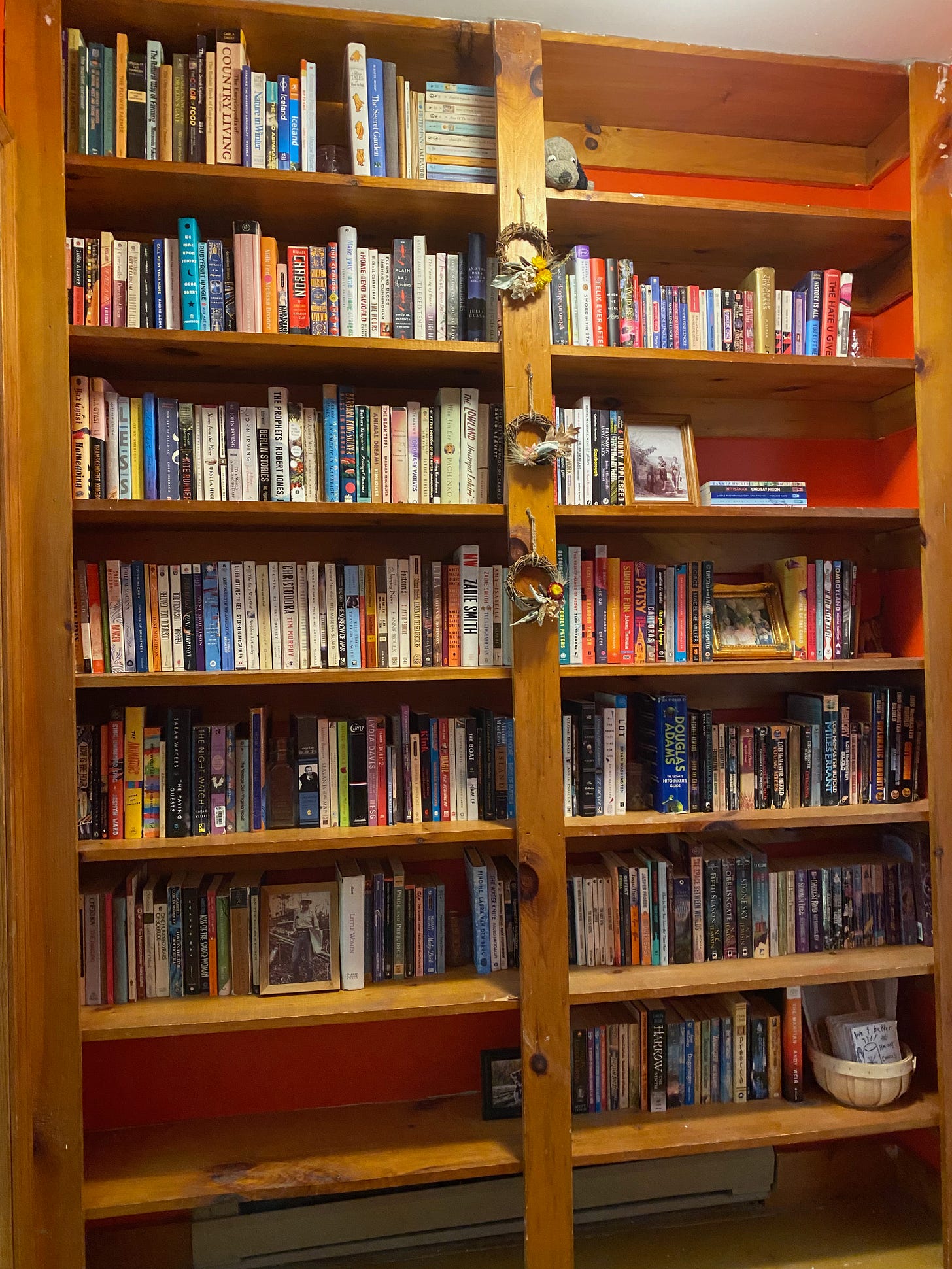

I’ve finally finished unpacking my books, so it feels like I actually live here now! I had a lot of fun arranging my books on these big shelves in the hallway. From top to bottom on the left side: farming books and children’s books, fiction (x3), short stories, books in translation and books published in the 19th century. On the right side: YA across all genres, books from my two favorite presses (Arsenal Pulp and Metonymy), my most beloved books, science fiction and fantasy (x3). I may end up changing it all, but for now I’m so happy with this organizational scheme.

Around the Internet

For my monthly Audiofile column, I wrote about three audiobooks that explore family in various configurations.

Now Out

No new books I’ve previously recommend are now out. But, for fun, here are a few bonus recs, 2021 releases I’ve enjoyed but haven’t highlighted in the newsletter: Cyclopedia Exotica by Aminder Dhaliwal (graphic fiction), Hola Papi by John Paul Brammer (essays), and We are Satellites by Sarah Pinsker (sci-fi).

The Boost

The news this week has been devastating. This post from Michelle Kim resonated with me:

Tuesday’s Anti-Racism Daily newsletter has some resources for how to support folks on the ground in Haiti, as well as a primer about the importance of supporting and donating to local organizations and mutual aid efforts, rather than massive NGOs.

If you’re on Instagram, Yeldah (@beautiful.bibliophile) is an Afghan bookstagrammer whose words and book recs I always appreciate. She’s put together a few guides for education and action regarding Afghanistan.

I have long admired the work of photographer Jess T. Dugan. In collaboration with Vanessa Fabbre, they created To Survive on This Shore, a collection of portraits and interviews with trans and gender nonconforming older adults. It is so, so beautiful. I highly recommend checking it out, especially if you need a dose of queer and trans brilliance this week.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Look, I know this is a picture of a shelf of flowers in my bathroom. I recently listened to The Power of Ritual by Casper Tee Kuile, and while it had its flaws, a lot of it resonated with me. The past few Sundays, I’ve gone to my community garden plot and picked a ton of flowers to arrange in these tiny old spice jars on this shelf. I love the ritual of it, the act of deliberately bringing this sliver of beauty into my home each week. I can’t wait to see how this shelf changes with the seasons.

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

Thank you for the tribute! So sweet! Looking forward to reading Shadow Life!