Greetings, book-eaters and treat-lovers! It’s April! Even I, lover of snow, dark, and cold, am happy. The sunshine! The little green buds! The return of robins and the summer colors of the goldfinches! I can’t say I’m looking forward to July (the worst month), but I am excited to revel in whatever weird spring New England decides to gift us with this year.

Nobody recommended any of this week’s books to me. I hadn’t even heard of them before buying and/or requesting them! I read them all solely because I trust the indie publishers who decided to bring them into the world. My trust was well-placed, because every one of these books is a winner. It feels like a miracle to me, but it’s actually because of the hard work of the actual humans who run these small publishing houses. I am so grateful.

The Books

Backlist #1: Double Melancholy by C.E. Gatchalian (Nonfiction, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019)

I bought this during a sale Arsenal Pulp had last summer. I’d never heard of it or the author, but the subtitle “Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man” sounded interesting, and Arsenal Pulp never lets me down. So I bought it.

This 134 page book absolutely rocked my world. G.E. Gatchalian is a queer Filipinx playwright and writer. In this slim book, he carefully examines the art (mostly books) that shaped him as a child and young man. All of this art—from L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables to the British series Queer as Folk to the work of Susan Sontag—was created by white people. With intellectual rigor and inventiveness, he methodically explores these works of art and his contradictory, changing relationships to them. These messy relationships create the central tension in the book: Gatachalian’s love for white Western art, the ways it shaped his early conservatism, and its contribution to his own erasure as a brown queer man.

He speaks to this in the introduction:

This book is a performance—a performance of decolonization. (Or at least an attempt at one—my newfound anti-colonialism must favor statements more modest in scope.) It acknowledges both how these (mostly white, largely Eurocentric) artworks bought me personal edification, and how, simultaneously, they invisibilized my political and social identities. The position I describe is one of radical synthesis: I wish to hold ostensibly incompatible points of view at the same time.

He approaches this “radical synthesis” by using more than one voice in the narrative. There’s the Voice Proper, the voice in which most of the book is written. It’s the voice of the author, Gatachalian’s present voice at the time of writing. There’s also the voice of Gatachalian’s journals. Journal entries, beginning with one made at age nine, are interspersed throughout the text. These are often painfully intimate. Gatachalian is a self-described artist and aesthete, someone for whom the pursuit of art has always been a kind of spiritual undertaking. His journals lay bare so much of his journey through many selves and ways of being. They are grandiose and agitated, self-aggrandizing and bleak.

Finally, there’s the Parenthetical Voice, which he describes as “the voice of my philosophical radicalism”. Throughout the text, this voice continually interrupts Voice Proper. It jumps in to contradict and correct, offering alternate interpretations, situating Voice Proper in a broader context, often criticizing Voice Proper for its ideas about race, art, colonization, and imperialism. Parenthetical Voice and Voice Proper sound nothing alike. Though the whole book is academic, it is also deeply personal, a blend of memoir, literary criticism, and analysis. Voice Proper embodies the personal: it’s moving, emotional, direct. Parenthetical Voice, though it makes important points, is dry and righteous (and sometimes humorous).

The interplay between these three voices—all of which, of course, are Gatachalian himself—made for one of the most invigorating, challenging, and ultimately illuminating reading experiences I’ve ever had. This book feels alive in a particular way—it doesn’t feel like a finished work, but like a window on a process. Gatachalian invites readers deep into the complicated process of untangling self. His use of multiple voices invites uncertainty and contradiction: he’s not done figuring it out. There’s no end to any of this thinking and striving and struggling and unlearning and celebrating. Gatachalian outlines a journey, certainly, a monumental one: from his youth as conservative brown queer kid who took refuge in the white art that was made easily available to him to a brown queer man wholeheartedly rejecting the white heteropatriarchy that created that kid.

He documents this journey with visceral emotion and academic rigor (some of which, I’ll admit, went over my head, but it didn’t detract from my experience of the book, it just made me want to read more, learn more, study more). But he doesn’t tell it simply, and he doesn’t tell it to its end, which doesn’t exist. The book ends with a breathtaking coda, written in a voice that’s maybe a conglomeration of all three voices, or maybe an entirely new one—in any case, it took my breath away.

I read this over the course of a weekend and I haven’t been able to get it out of my head since. It stretched me in all the best ways, shook up my brain, opened up new ways of thinking about story, art, memory. I haven’t nearly done it justice here. If you’re up for something singular and uneasy and messy, these 134 pages of complicated thought are worth your time and then some.

Backlist #2: How To Not Be Afraid of Everything by Jane Wong (Poetry, Alice James Books, 2021)

Once again I find myself in the position of wanting to recommend a wonderful book of poetry, but struggling to review poetry coherently.

I love poetry that is grounded in the physical, and this book is so physical. It is about food and rot and gardens and streets and bodies and furniture. Most of the poems concern Wong’s family history in China in the US. She writes about her childhood with immigrant parents, her grandparents in both the US and China, and the legacies and lineages of story, language, food, culture, pain, lack, and longing that she has and hasn’t inherited from her family. Her imagery is striking—precise and stark and full of movement. She often transforms a concrete image into something strange, twisting its meaning into a new shape.

Late July, my grandmother clips green vines with

her claws, wears it as jade. The garden simmers in brackish

brown slush. Rot like armpits, rot like lizard eyes. I dream

of string beans so long, they lineage.

The longest poem in the collection, and my favorite, is a piece called “When You Died”, which is about the Great Leap Forward and the massive famine that resulted from it, in which millions of people (an estimated 36 million according to Wong’s notes) died from starvation. Wong’s grandfather survived the famine, though most of his family did not; he was adopted by an older man who had also lost family members. Wong’s mother was born at the tail end of the Great Leap Forward, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution.

The poem is made up of untitled sections, all of which take different forms. It begins with the line: “I went to the library to find you.” The whole poem is about searching—not only Wong searching for her grandfather, and for the family members who died before she knew them—but searching for the meaning of searching itself. What does it mean to tell a history, yours but not yours? What does it mean to hold that history in your body? Why do we tell the stories of our ancestors? Is it to honor them? Is it to find ourselves? There are so many painful questions in this poem about silence and language and the spaces between them.

One of the most poignant sections is a series of questions that Wong directs at her grandfather. At first they’re somewhat concrete:

Were you hungry? Were your feet clean

or covered in dirt? Who cut your hair?

Did the oil in your hair smell of gasoline?

Corn? Mint leaves?

But they eventually morph into questions that feel more like dream logic (“Was I a pigeon in this city in your dreams?”) So much of the poem is like this, swinging between the concrete and the strange. It’s the story of a catastrophic and violent event, a catalog of loss, a remembrance. But it’s also about the purpose of language and art, about how to make sense of what is incomprehensible—and what it means to try.

Did you have a name and did the army

take it away? Did you try to holdonto your name? An armful of emptiness

is better than nothing. You do notbelieve me? Tell me then: what is the use

of making sense during a timelike this, during a red sky like that,

dangling about like a sweetslice of meat you want to devour?

Upcoming: Violets by Kyung-Sook Shin, translated by Anton Hur (Fiction, The Feminist Press, April 12)

This is a bleak book. I don't have much patience for bleak books anymore, especially queer ones, but I loved this. I loved it for its honesty and its small moments of reprieve. I loved it for the beautiful descriptions mundane tasks, recounted with so much emotional depth. I loved it for the structural beauty of the narrative.

Growing up in a small Korean town, San finds joy in her friendship with another girl, Namae. When Namae rejects her tentative expressions of queer love, San has nowhere to turn—especially not to her mostly-absent mother. This profound loss sits like a cold stone at the center of the novel. It reverberates through everything that happens to San afterwards, even when—perhaps especially when—she’s not aware of the loss, or refuses to name or acknowledge it as such.

As a young adult, San finds work at a flower shop in Seoul. Her loneliness is palpable. She's good at her job, and she likes her co-worker, who soon becomes her friend and roommate. But she's carrying around open wounds she can't see, and into the space they create inside her, patriarchy rushes. Misogyny rushes. Homophobia rushes. A society that does not see her and does not care about her and does not protect her rushes. All these heavy, horrible, rushing things fill up the space inside her, next to that open wound, and that's a lot of pain for a body to hold.

While it’s made up of beautifully written scenes and details about ordinary life, the book is also a catalog of these rushing things, the channels they carve in San’s life, the ways they keep her from opening herself to other people. She wants so badly to be loved, to be seen, to know ease. She strives for these things, and they trickle into her life in small bits and pieces—a day working at the farm connected to the flower shop, evenings at home eating dinner with her roommate. But none of it is ever quite enough.

This book is full of so many violences, so many small stinging moments of rejection and despair. I found it hard to read at times, but never gratuitous. What's happening to San—her all-consuming despair, the danger inherent in the men around her, her obsession with being wanted—is obvious to the reader, but not to her. It's a spectacular character study, intimate and masterfully constructed. San speaks loudly. She speaks for herself, even through her despair. This, perhaps, is part of why the book hooked me, even when I began to dread where it was going. San never stops being herself. She never stops telling her story. She never stops trying to get to the bottom of why she feels the way she does, why her life hasn’t gone the way she dreamed. She keeps on speaking, and in the speaking is a kind of hope.

That said, I wouldn't have loved it so much if it had been purely grim, grim, grim. Kyung-Sook Shin doesn't reduce San to her pain. She also captures the rhythms of everyday life—especially new friendship, and working with plants— in exquisite detail. I have worked on farms, with flowers, and in garden centers, and the detail around the experiences of working in these environments delighted me. I’ve never been in a Korean flower shop or on a Korean farm, and yet so many of scenes in this book felt bone-deep familiar to me. The smells and colors of certain plants. The repetitive work of unloading a large plant delivery. The humid warmth of a greenhouse. These are all such specific, tactical experiences, and Kyung-Sook Shin writes about them with graceful ease.

Translation is a strange and mysterious alchemy that fascinates me endlessly. I could not get over the elegant beauty of this novel, and I am endlessly grateful to Anton Hur, and translators in general, for doing their work and art. It’s an art I cannot fathom, a creating-of-space that seems almost magical to me. Reading this book reminded me just how much beauty translators bring to the world. I’m excited to start working through translator backlists the same way I work through the backlists of beloved authors!

This is a hard, haunting, beautiful book, one that will stay with me forever. It’s out next week from The Feminist Press, and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

This bread recipe comes from one of my favorite cookbooks, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s River Cottage Veg. He calls it “magic bread dough” because you can turn it into so many things: pizza, flatbread, breadsticks, rolls! I’ve made it into flatbreads many times, but this weekend I wanted something a little more adventurous, so I made it into rolls stuffed with a delicious feta and garlic filling.

Feta-Stuffed Rolls

Makes 8 rolls

These are quite intense with their feta-garlic filling. I love them! But you could also swap out half the feta (or all of it) for an equal amount goat cheese, or another mild soft cheese. Or half the amount of cheese and add an equal amount of something else—caramelized onions, sun-dried tomatoes, chopped fresh herbs, etc.—for a less cheesy stuffed roll.

Ingredients

For the rolls:

250 grams (2 cups) all-purpose flour

250 grams ( 2cups) bread flour

1 tsp yeast (he calls for instant, I used active dry, either will work)

1 1/2 tsp salt

1 Tbs olive oil

1 1/3 cups (325 ml) warm water

1 egg (for the egg wash)

sesame seeds, for sprinkling

For the filling:

8 oz feta cheese

3 Tbs olive oil

1 small head garlic, separated into cloves and peeled

1 tsp Aleppo pepper

Make the dough: In a medium bowl, combine the flours, salt, yeast, olive oil, and warm water. Use your hands to mix until a shaggy dough forms. Turn out onto a lightly floured surface and knead until smooth and elastic, 5-10 minutes. Place the dough into a lightly oiled bowl and let rise, covered, until doubled in size, 1-2 hours.

Make the filling: Combine all ingredients in a food processor and blend until smooth. Set aside.

Assemble the rolls: Tip the risen dough onto the counter. Using a sharp knife or bench scraper, divide it into eight equal pieces. Working with one piece at a time, roll out a small circle, about 6 inches in diameter. Place a heaping scoop of the feta mixture in the center of the circle. Fold in the four sides of the dough to mostly cover the cheese, then pinch and fold again to fully hide the filling.

Use your fingers to carefully pinch all the seams closed. (Take your time with this—I was not careful and a few buns leaked filling in the oven.) Once all the seams are pinched shut, gently roll the dough ball on the counter to smooth it out. Place seam-side-up on a baking tray lined with parchment paper or a silicone mat. Repeat with the remaining dough. Cover the tray with a dish towel and let rise another hour.

Bake the rolls: Preheat the oven to 425. Beat an egg with a splash of water. Liberally brush the tops of the rolls and sprinkle with sesame seeds. Bake until golden brown, about 15 minutes.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Shredded Chicken & Sweet Potato Soup

This is a slightly more complicated recipe than the ones I usually share, but only because it requires a few steps and more than one pot. It’s actually quick to make, and it is so, so delicious. I am annoyed that I made it last week and it’s all gone now. I didn’t freeze any (why?) but I recommend doing so if you have extra because yum!

Cook the chicken: In a small saucepan, combine ~1 pound of chicken thighs, a quartered onion, a handful of peeled, smashed garlic gloves, a sprinkling of chili flakes, an inch-long nub of ginger, and some salt and pepper. Add water to cover by a few inches. Bring to a boil, and then reduce to a simmer and cook until the meat is tender, about 30 minutes. Remove the chicken from the pot to cool; once it’s cool enough to handle, shred it with your fingers. Strain the cooking liquid and set it aside—this will become the broth for the soup!

Make the flavor blend: In a food processor or blender, combine a bunch of cilantro, the juice and zest of a lime, a few peeled garlic gloves, a quartered jalapeño pepper, and some chopped or grated ginger. Pulse until smooth. Set aside.

Heat some neutral oil in a large pot. Chop a sweet potato or two into small chunks. Add that to the pot, along with the blended cilantro mix. Add the chicken stock (it should be somewhere around four cups) and one can of coconut milk. Cook at a steady simmer until the sweet potatoes are soft. Add the shredded chicken and adjust seasonings to taste. Serve over rice with wedges of lime.

The Beat: Smile: The Story of a Face by Sarah Ruhl, read by the author

So far I am enjoying this quiet memoir about playwright Sarah Ruhl’s experience with Bells palsy, which caused half of her face to become paralyzed just after she gave birth to twins. It’s a series of short meditations, most of which center on her changed face and her relationship with it. But she also writes about motherhood, playwriting, the act of smiling in general, medical history, religion, her marriage, and more. It reminds me some of The Sound of A Wild Snail Eating: both are intimate yet far-ranging memoirs about women and illness.

The Bookshelf

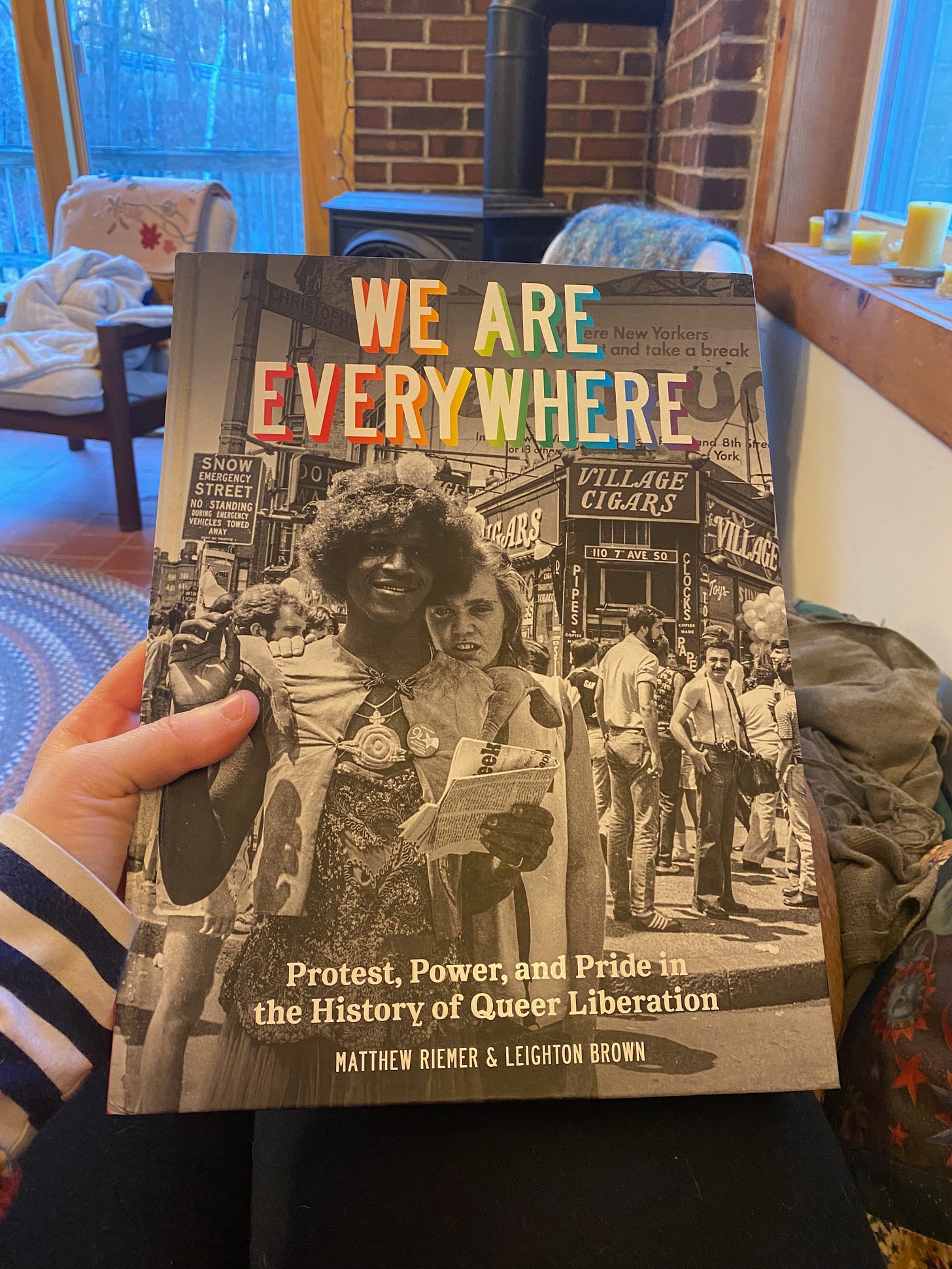

A Picture

I am always trying out new morning reading rituals. Over the weekend I took this glorious book off my shelf, where it’s been sitting for several years, and started reading it. I’ve been reading a few pages every morning before work. Starting every day by drinking in photos of queer ancestors and queer protest is absolutely the best.

Around the Internet

For Book Riot, I wrote about how my commonplace book has changed the way I value the books I read. I also pondered whether or not I’ll ever read SFF again, and wrote about why I love the “Western Canon”—not for itself, but for the retellings it makes possible. My review of True Biz is up on BookPage.

Now Out

Hurray! So many great books I’ve recommended here are out this week: Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel; True Biz by Sara Nović; Fine by Rhea Ewing; and Panpocalypse by Carley Moore. Go forth and find yourselves copies of these beauties.

Bonus Recs: Beloved Indie Presses

Rather than bonus book recs, I have some bonus indie press recs. I love so many indie presses, but there are a few I simply can’t imagine reading without. All the endless gratitude to Coffee House Press, Milkweed Editions, Metonymy Press, Seven Stories Press, Catapult & Counterpoint, Tilted Axis Press, and Button Poetry.

The Boost

I loved this interview with rabbi and activist Elliot Kukla about care, grief, rest, and disability wisdom.

Even though the prevalence of Zoom has made events of all kinds more accessible for lots of folks (including introverts like me!), I still struggle to attend them. I want to change that! So I’m going to start sharing online events I’m excited about here. This is happening tonight and it looks great:

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: This sign used to sit in the garden we made just for fun at my old farm. Now it hangs on my porch. I painted it as a starry-eyed twenty-something farmer, but I still find the quote miraculous.

And that’s it unit next week! Catch you then.

I really enjoyed Smile, and I just finished The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating the day before yesterday! I hadn't drawn parallels between the two, but of course, you're right that they have a lot in common. Great issue as always, Laura!