Volume 5, No. 5: Collective Care, Citational Love, & The Unmuseum of Tree Parts

April Reading Reflections

Greetings, book and treat people! Every time I sit down to write this newsletter I think, “okay, I’ll make it short this time!” Well. I am who I am. April was a weird month for reading but a good month for art, thinking, and being with friends.

I saw a fox (twice). It’s been raining for days which is spring bliss. The US government is bent on destroying most everything I love. I watched this amazing documentary about Nikki Giovanni (it’s on Kanopy). I visited one of my favorite current exhibitions at Mass MoCA. I’ve been drawing a lot of wisdom from Octavia Butler. I listened to this album all month and it’s perfect. I made a carrot cake. I got to see Hanif Abdurraqib live! I joined the rad collective I’ve been volunteering for that sends books to incarcerated folks. I visited with my best friend from childhood who I hadn’t spoken to in almost 15 years. I got a video tour of a friend’s collection of art books. I’m trying out a 5/4/3/2/1 format to tell you about my month. Let me know what you think!

Five Incredible Women…

…whose work I reveled in in April.

Emily Dickinson

I wrote a little bit last month about Emily Dickinson. I am now fully in my Emily Era. I’m still working my way through her complete poems, but I did read Open Me Carefully in its entirety. It’s a collection of the letters Dickinson wrote to her neighbor, sister-in-law, and beloved, Susan Huntington Dickinson. I adored it for a million reasons. Like this: “I must wait / a few Days / before seeing / you - You are / too momentous.” I mean. The gay drama. And this: “The things of / which we want / the proof are those / we knew before -” The syntax!

I am obsessed with the idea of letter poems, which is what a lot of the book is—letters to Susan, but written as poems. I’ve also been thinking pretty much constantly about small, intimate forms of publication (a letter to a friend vs. a book deal with Penguin Random House).

Dickinson is so weird and so surprising and her language does strange things to me. The way she constructs language. I can’t get over it. I am also having this experience of falling in love with the most famous poet from my home state in my late 30s, having never read her before, and there is something miraculous about it. She is delightful. She pierces me. She is so, so frustrating. I feel a bit dizzy (complementary).

I also watched the show Dickinson, which I enjoyed a lot—it’s extremely silly but a lot of fun. I’m excited to spend some time at the Emily Dickinson House this summer, because my Emily Era is just getting started.

Octavia Butler

I reread Parable of the Sower for my sci-fi class for the first time since 2007. My memory of it is of a bleak, horrifying, cruel world, devoid of hope. I was surprised, on the reread, to discover how much tenderness there is in it. The world was different the first time I read it, but I was also so much younger (21). I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means—about me, about the ideas and philosophies I’ve internalized, about my own beliefs—that I remember it in such a particular way.

I don’t think I’ve become more hopeful, really. The world has certainly not given me any reason to become more hopeful since 2007. And yet, reading this book in 2025, after 18 months of genocide in Palestine, in the midst of rising fascism, watching as a hateful regime dismantles the systems and institutions that keep people alive (yes, btw, all of these institutions are rotten to the core—but we cannot dismantle them without something new to build in their place)—reading this book in 2025, exhausted and terrified by the onslaught of anti-trans and anti-immigrant policies, by censorship and white supremacist glee and so much cruelty—well, what struck me about it was the care.

The world Butler depicts is the world we live in. What’s radical about it is not that she predicted what would happen back in the 1990s, but that into that future of climate disaster and extreme poverty and religious fanaticism and white supremacist violence, she wrote a protagonist who believes in change. She wrote a protagonist who is determined to live, and who understands that in order to live, we have to care for each other. Lauren is not some bastion of moral perfection. She, like many of the other characters, uses violence when she has to. But she never loses sight of what she wants—community, purpose, a life beyond suffering. And she never loses sight of what that future will require of her: that she tether herself to others. To ask for, receive, and offer help. To trust. To welcome in. These are the acts of care that allow Lauren and her friends to survive.

The world of the Parable books is bleak. But I found immense comfort in rereading this novel now because Butler’s worldview, in essence, for me, is one of care. It’s “we owe each other everything.” It’s “we are each other’s harvest, we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” This is a novel that does not refuse despair but does not treat despair as an endpoint. This is something Hanif Abdurraqib spoke about beautifully at a reading recently—that he feels despair, and that it is an emotion that leads him back to love, to the people he loves, to the ways in which he can make small pockets of the world livable.

Who are you caring for today, and how? That’s the question this book dares us to ask ourselves.

Christina Sharpe

I finally got to Ordinary Notes, and it was the best book I read in April. It is its own language and form. It is, I think, wake work. It is a love letter to Sharpe’s mother, and an exploration of the way she used “beauty as method” to celebrate the richness of Black life. It is, itself, beauty as method. It is a book of Black dailiness, an interrogation of memory and memorial, a meditation on visual art and what it can and cannot do. Sharpe writes into and through the “past that is not past” and weaves of it, weaves of art and film and poetry and criticism, of violence and mourning, of language and familial love, of death and photography, something untranslatable and expansive. I cannot do this book justice.

Instead, a few love notes back to it:

Sharpe is so attentive to form. She holds it like a poet. In this book, note is form. Like she did with “wake” in In the Wake, here she explores the many meanings and registers of note. She sounds notes, she notes, she takes note, she writes notes, she notices. I have never read a book written in notes like this before. It is profoundly moving. It creates space for criticism and analysis on multiple levels. It creates space for play, intimacy, and silence, for informal and formal invitations. Notes in this book are doors, portals, widows, walls, thresholds—there are many, many places here white readers cannot enter. There many, many places where we are invited in. I will never be done thinking about the languages(s) Sharpe creates in this work.

I read In the Wake earlier this year, and have been thinking a lot about its lineages, about just how many writers, scholars, and artists not only cite Sharpe, but move alongside and through her. The lineage goes backward and forwards. That lineage pulses through this book. It is not an individual act. It is collaborative, communal, ancestral. There are so many writers and artists in these pages, so many Black women, so many spirals of shared grappling, loving, wondering, contradicting, questioning, tending. In a BTC interview with Danez Smith (who mentioned Sharpe!) David Naimon used the phrase “citational gestures of love” and I cannot stop thinking about it. This book is an embodiment of citational gestures of love.

Hilma af Klint

I’d never heard of Hilma af Klint, a Swedish artist, mystic, and spiritualist who made absolutely incandescent abstract paintings in the early 1900s. I haven’t heard of most artists, and this is another pleasure for me—it is such a joy to come across something I did’nt know about before, and then get to love it loudly.

I watched this documentary about her, which I thought was fine, but it did not go into nearly enough depth for me. The exhibition catalog from the 2018 show at the Guggenheim is on its way to me via the library, and I can’t wait to spend some time with it.

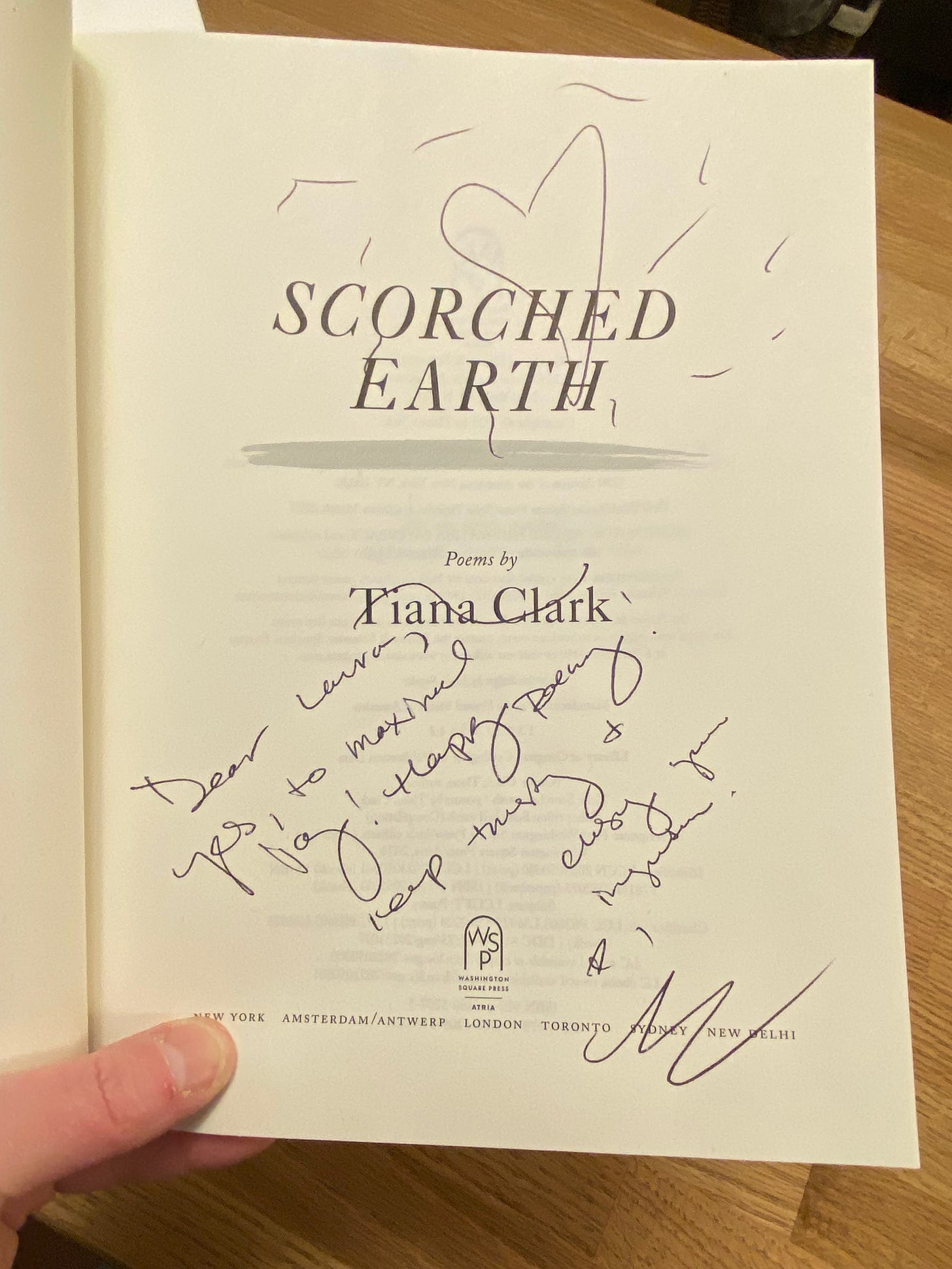

Tiana Clark

In early April I got to hear Tiana Clark read from her new book Scorched Earth. She is amazing! She is so smart and generous. Her poems are full of maximalist energy. They are big and unwieldy and loving and overflowing with epigraphs. I love her ekphrastic work and I love how dense with citations her poems are. Citational gesture of love after citational gesture of love.

After she read, she and Ocean Vuong had an amazing, illuminating conversation about art and process and joy and form and so much more. Vuong kept bringing other writers and thinkers into the conversation (he read a passage from a book by Sara Ahmed), which reminded me of how my celebrity crush David Naimon talks with poets: densely, expansively, citationally. One of my favorite things was watching Tiana Clark take notes in the middle of the conversation—me too! My brain was leaping all over the place. Here are a few things I scribbled down:

“Process as a mode of curiosity and delight.” (Ocean Vuong)

“Failure is a form.” (Tiana Clark) “Rest is a form. “ (Ocean Vuong)

P.S. If anyone can figure out what the sentence starting with “keep” says in Tiana’s inscription, please let me know.

Four Joys…

…that kept me going.

Voice Notes

My friend Charlott and I have been exchanging long voice notes about books and art and gardens and language and our lives. Sometimes we talk about voice notes as form and I love that, too. She is Berlin, and I am here in the woods of Western Massachusetts, and there is something magical to me about our words and ideas and laughter traveling back and forth asynchronously. There’s something magical about how voice notes invite informality and rambling, but also invite slowness, care, intentionality. It’s been a big big joy and I am grateful for it.

Natural Ink

Our final project in my visual concepts class combines some of my favorite things: printmaking and plants. The prompt was to make some natural ink and then use it to make prints that have something to do with the process of making the ink. We’ve done a lot of experimenting with both ink-making and printmaking, looking at different ways to turn natural inks into printmaking inks, and different ways to print onto paper we’ve painted on with natural inks.

I made ink with onion skins (below), hemlock bark, and acorn caps. After a lot of playing, I decided I wanted to make washes with my inks, and print images on top of them. I had so much fun painting with these inks!

I got really into the idea of using plant material as part of the printing process, and my professor showed me how. She is great! I am so in love with this process. I want to keep doing it forever and ever amen. First I inked a plate and laid out all of my botanical material on it. The print you get from that process looks like the third from left in the top row: bright silhouettes on a very dark background (see also the fourth from left in the second row).

Next I removed the various leaves and petals, now carrying ink on one side, and placed them on a piece of white paper, like stamps (bottom right). I also ran the plate, now missing the botanical material, through the press again (second row third from left and bottom row first on left).

For printing on my natural ink washes, I used the inked plant material like stamps. Here are some pages about to go through the press:

And here’s a finished print, an oak leaf on top of a wash of natural ink made with acorns:

I’ve enjoyed every single project in the two visual concepts class I’ve taken, but this process has been the most magical. It feels like the beginning of a life long love affair. Now to find access to a press…

Book Club

I started reading Emily Dickinson because of my lovely in-person book club. We all read some of her work and then brought some poems to the meeting to discuss. We talked about death and Mary Oliver (of course), and the Civil War, and what an artist tells you about themself in their work, and the steamy gay letters Dickinson wrote, and depression and mystery and queerness and the poems we loved and the poems we didn’t understand and a million other things and it was just an absolute and utter joy from start to finish. And! My friend Kristin made coconut cake using Emily Dickinson’s recipe! Also! There was Emily Dickinson death metal! My friend

wrote a little bit about it. We laughed so hard. I love my book friends.Daffodils

I love them.

Also, this Emily Dickinson poem.

Three Perfect Trees…

…I visited with..

This is one of the trees I see on my daily morning walk. I adore it.

There’s this particular season in early spring, when the leaves on the oaks and maples are just unfurling, when the leaves are present but haven’t yet hidden the tree’s branches, a season during which you can see time moving. It only lasts for a breath, this season of multiplicity, this season when trees speak in both their summer syntax and their winter syntax. I want to write a hundred poems about it but no poem will come close to the beauty of this ephemeral tree grammar.

I saw this perfect, curling, prickly, spiraling tree in the Arnold Arboretum. It was even more perfect because of who I was with: I finally got to meet my friend Surabhi in person when she came to Boston for a conference! It was a delight and btw her newsletter is great!

Two Things I’m Thinking About…

…constantly.

Citation as Art Form

My second semester back in college after nearly 20 years ends next week and to say it has been incredible is an understatement. I’m struggling to express how much I love being a student, which is saying something, since I am quite wordy. I remember how excited I felt back in September, during the first week of classes, how I wanted to shout and shout about all the doors opening in my brain and heart. (And if you follow me on Instagram, you know I have been shouting!)

A part of me didn’t believe that I’d still feel that way after a year. A part of me, I think, was waiting for the cynicism and boredom to set in, was expecting some of the misery of my first attempt at college to creep back in. There have been hard moments and less-than-perfect moments. But my excitement and joy and curiosity haven’t faded. If anything, I’m more excited now than I was in September. It’s like I’ve been remade. It’s hard to describe the experience. School isn’t everything—it’s far from everything—but it is what is leading me, right now, deeper into my life and deeper into the world. I still don’t know exactly where the journey is going, but I know it is making me more caring, more curious, more invested in asking big questions and protecting what I love and making change.

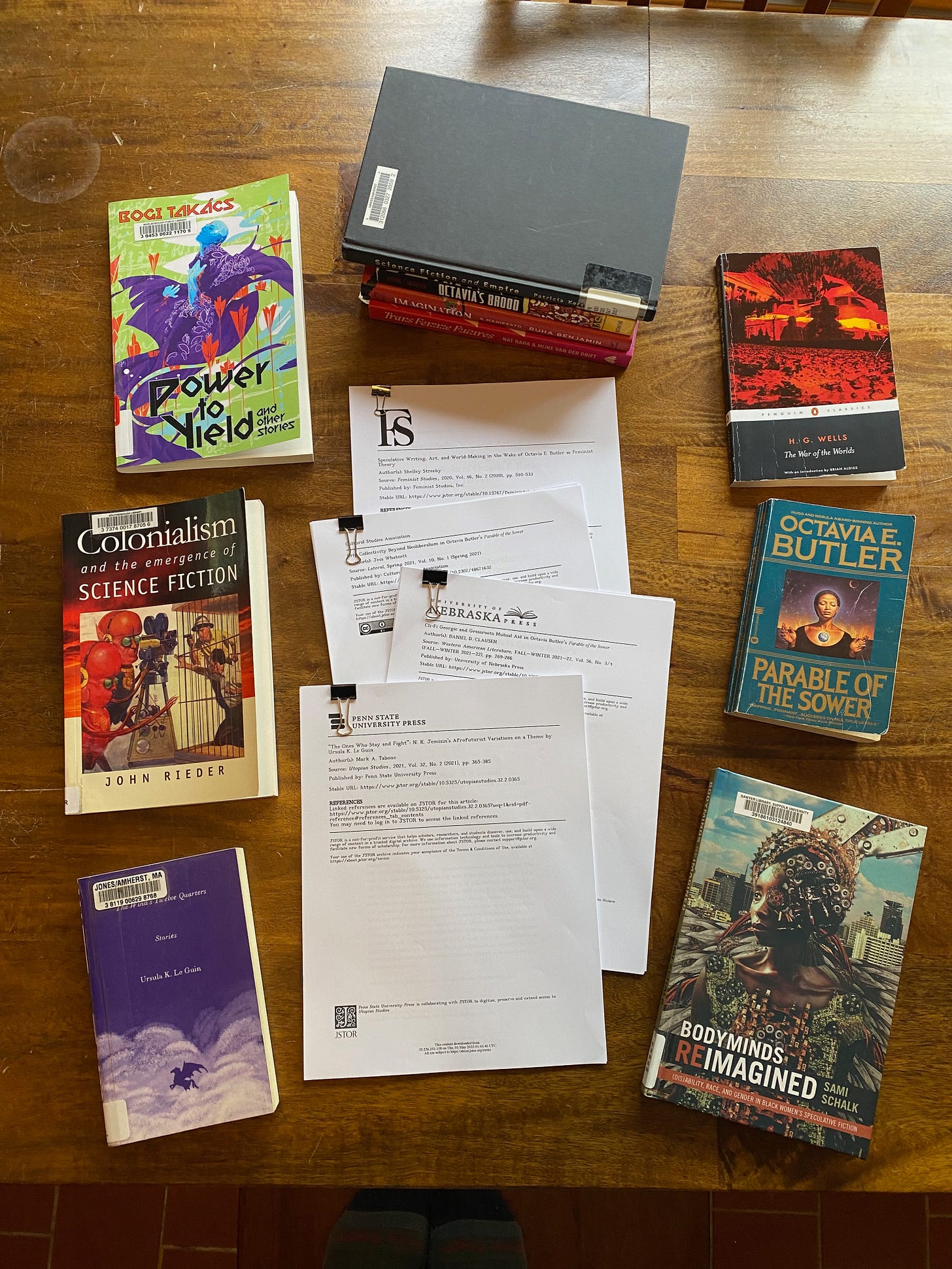

I’m currently working on my final project for the sci-fi class I’m taking. It’s a paper about Octavia Butler, H.G. Wells, the colonial imagination, and how authors do and do not portray acts of collective care in their work. I spent most of last weekend reading and taking notes. I read chapters from a few different academic books, several journal articles, and a few short stories.

This whole process has delighted me: the reading, the thinking, the untangling. But what surprised me the most is how much I love the actual, physical, methodical work of citation. I don’t just mean getting to think with and against other scholars and writers. I mean I loved making my Works Cited page. I mean every time I insert a parenthetical citation into a paragraph, something in me lights up with pleasure. There is something about this practice that feels expansive to me, like an endless conversation. It makes writing feel relational.

One of my favorite things about poetry is how citational it is. I love ‘after’ poems. I love poems full of other poets. I think poetry is inherently citational—a defining feature. So this love of citation in academic writing isn’t really anything new (and I do think citation, like anything—language, art, poetry—can be used in service of violence). But wowie, is it joyful.

Uncollecting

I’ve been thinking a lot about collection and and what it might mean to uncollect. One of the coolest projects we did in my visual concepts class this semester was a gumball machine takeover. Nick, a local artist and owner of Sadie’s Bikes in Turner’s Falls, has retrofitted a bunch of gumball machines, and periodically invites artists to fill them. For the GCC Student Art Show, everyone in my class made different tiny art objects to put inside 2” capsules, which people could then get for 50 cents at the art opening.

I collected bits of trees from my daily walks—acorns, bark, pine cones—and put them inside the capsules with a little book called The Unmuseum of Tree Parts. In each book, I wrote a little bit about the tree part, and instructed recipients to spend some time with it, listen to its stories, and then uncollect it by placing it somewhere in the world it might like to live.

What can we uncollect? How can we cultivate relationships with nonhuman beings that are not based in collecting and defining? Would would it mean to create uncollections instead of collections? What would a poetics of uncollecting look like? A praxis of uncollecting? I’m so excited to keep thinking about this.

One Moment of Loud Care…

…among many.

Recently I was talking to my friend Surabhi about anger, and she said something that rewired my brain: that a lot of anger is actually loud care. I’ve been thinking about this constantly. I have a lot of thoughts about anger that I won’t go into here, but I often feel like everyone around me is full of rage, and it’s not that I’m not, exactly, but—what I feel more often in my body is sorrow. Bottomless sorrow.

Recently the NEA announced that they will be terminating grants for dozens of arts organizations, including some of my most beloved publishers, publishers who usher gorgeous, complicated, visionary work into the world. Milkweed Editions, Alice James Books, BOA Editions, Nightboat Books, Coffee House Press. It is hard to imagine being a writer or a reader without these presses.

There is so much to be angry about and this is a tiny sliver of it. This is just the thing that happened on the day I sat down to write this newsletter. There are the abductions and deportations of students protesting genocide. There is the genocide, ongoing in Gaza. You know as well as I do that this paragraph has no end. You know as well as I do that these horrors are not comparable.

When my friend described anger as loud care, something about how I relate to the world clicked into place. I am not angry at the current regime because of the evil things they are doing—or rather, yes, of course I am, but it is because of my love for the people and lives they are destroying. I am not interested in that man, in any of those men. I don’t spend any time thinking about him. I spend time thinking about what and who I love—specifically, as in BOA Editions, and generally, as in: Independent publishers. Children. Artists. Parents. Books. Trees.

You can donate to any of these presses I love so much by clicking on their names above. You can also read this poem by Aracelis Girmay and let it direct you toward your own particular actions of loud care. Wishing you all sweetness and strength, as ever.

the loud caring made me think of parks and recs and Leslie Knope's "people caring loudly at me" https://screenrant.com/leslie-knope-quotes-that-make-us-miss-parks-rec/

I know you are podcastly monogamish with BTC right now, but you might enjoy the citations from this episode on citational practices from Secret Feminist Agenda https://secretfeministagenda.com/2019/03/15/episode-3-21-citing-your-sources/