Greetings, book-eaters and treat lovers! The anti-trans legislation in the U.S. keeps escalating, and it is really scary and really bad, and I am so heartbroken and rage-filled and exhausted, and I am thinking about all of my trans family and beloveds, and everyone who is more heartbroken and terrified and exhausted than I am, and I would like to burn it all down. I’ve collected a few resources at the bottom of today’s newsletter, with more to come.

All three of today’s books are incredible—three of my favorites of the year so far! They are about the possibilities of movement. They are about queer philosophy and radical choreography and the many ways in which people from historically marginalized communities—past, present, and future—have danced and moved and shaken and tripped their way through impossibility, toward liberation. These books are fierce openings, wild imaginings, raucous celebrations, and mourning songs. They are about objects hurtling through space and bodies hurtling through time and ideas hurtling through brains.

The Books

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr (Historical fiction, 2022)

This novel is set in 1929, and takes place mostly on a train hurtling across Canada. Baxter is a sleeping car porter who dreams of becoming a dentist; he’s been saving for dentistry school for eight years. So he takes all the work he can, even when it means going with little to no sleep for days on end, and putting up with nearly endless racism from white passengers.

It’s so close and intense. The way Mayr uses detail and repetition is chilling. There’s not much plot. The train leaves Montreal and heads for Vancouver. It gets stuck in the mountains for a while. Baxter does a fair bit of thinking and remembering—there are flashbacks, some backstory—but mostly, he goes through the motions of his job. He folds sheets, makes up berths, shines shoes, deals with dirty towels, fetches drinks. On and on and on it goes. Sometimes Mayr uses the exact same words to describe events, so that small actions are repeated over and over until they start to feel unbearable, a never-ending series of stings.

The racism is endless, a string of microagressions (and not-so-microagressions) that made me want to hurl things and throw people off the train. It’s hard to describe just how tense and bleak the atmosphere is. Some of what Baxter has to deal with is outright and obvious (like passengers calling him “George”), but a lot of it is insidious and insistent. On the train he becomes invisible. His rich inner life, so present in the narration, is flattened and ignored in his human interactions. The white passengers don’t see him, and many of his fellow Black porters don’t see all of him, or think him strange—his queerness, his love of sci-fi stories, his desire to be a dentist.

Baxter does his job with the constant awareness that one complaint from a passenger could get him a demerit, could cost him his lifelong dream. He does his job with the awareness that grinning and bearing it will get him tips, and tips will get him what he wants, but underneath, he’s burning up with rage. He’s incandescent with rage, and yet he keeps himself so controlled, and I found it hard to breathe while reading. It is outrageously unjust. The monotony, the simple plot, the repetition, the movement of the train, the looming sense of inevitability—it all heightens the daily, brutal monstrosity of the job. Mayr doesn’t hit you over the head with it; she doesn’t need to. It’s incredibly effective. It’s visceral.

There’s also an element of sleep loss that makes parts of this novel feel like a waking dream and parts like a waking nightmare. Management obviously doesn’t care about the wellbeing of the porters, so Baxter only gets tiny snatches of sleep. It gets even worse when the train encounters an unexpected delay in the mountains and is stuck for days. Baxter starts hallucinating. He sees things that aren’t there. He starts to wonder if things he’s said or done or felt are actually only happening in his head. He questions his own memory and experience, and it’s chilling, because this is basically the definition of gaslighting. There are plenty of horrors Baxter experiences on the train that no one else acknowledges, and then there are these weird visions and uncanny sensations, and where’s the line? What’s real? It’s terrifying.

Like most books I love, this one isn’t all bleak. There are moments of relief and levity, and even some poignant moments of queer joy. Mayr balances the real danger of being queer and Black in the 1920s with Baxter’s fierce and specific delights, with scenes of connection between queer Black men that felt, to me, transcendent.

I’ll be thinking about this one for a long time. It’s beautiful and painful, a little bit whimsical and a lot terrifying, a weird and brilliant blend of hyperrealism and hallucinatory surrealism.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman (History, 2020)

This astonishing world-opening book is easily the best history I have ever read. I’m hesitant to review it, because I know I can’t do it justice without writing a review that’s six times as long as this one will be. There is so much I want to say about it, and at the same time, I’d like to read it again before articulating any of my thoughts, because even though I read it slowly, there is just so much going on in this book. It’s not so much a book as doorway, a portal, a praxis of history, a continuing story.

So I’m not going to get into the content. It’s about Black women, mostly in New York and Philadelphia, in the early part of the 20th century, and the many ways those women lived big, beautiful, raucous lives, despite constant state surveillance and prosecution, despite the racist systems that wanted them dead, despite poverty and prison, despite. In the introduction, Hartman writes: “This book recreates the radical imagination and wayward practices of these young women by describing the world through their eyes.” She goes on:

The endeavor is to recover the insurgent ground of these lives, to exhume open rebellion from the case file, to untether waywardness, refusal, mutual aid, and free love from their identification of deviance, criminality, and pathology; to affirm free motherhood (reproduction choice), intimacy outside the institution of marriage, and queer outlaw passions; and to illuminate the radical imagination and everyday anarchy of ordinary colored girls, which has not only been overlooked, but is nearly unimaginable.

She does this, in an extraordinary explosion of stories, by inhabiting the lives and voices of these women. It is visceral and immediate. Everything about the way this book is built and structured is radical and revolutionary. The italicized phrases throughout, which represent direct quotes from the chorus—those people who have been so long ignored, deemed unimportant to history. The way Hartman weaves footnotes into the narrative. The short chapters that read like prose poems, and the longer ones that trace specific lives and histories. The space she makes for untold stories. The chorus is always there, impossible to ignore. It’s hard to explain this, but I’ll try: the richness of this history makes it both bigger and smaller. As in, it is always painfully clear that for every life in this book, there are one hundred other lives, as singular and important, still untold. Using an imperfect archive that mostly exists to uphold white supremacy, Hartman imagines and explores countless real acts of resistance, small daily loves, queer families, untraditional motherhoods, joyful sexual exploits, struggles, anger, loss, revolution. Through her careful telling, emotional investment, and exquisite scholarship, she makes space for a thousand more. This book does not end.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how much I hate the idea of “reclaiming” history. Reclamation implies that something has been lost. I don’t like where it places the action—it puts the impetus to uncover and excavate on the “othered” historian, rather than on the forces and systems that have shaped the narrow way we understand history. Stories of queer love and Black resistance have not been lost—they’ve been purposely stolen, deliberately hidden. For me, the expansiveness of Hartman’s history is a refusal of reclamation. She upends the default, rejects the white gaze, centers a difference archive, declares truths truths too long “unthought because no one could conceive of young black women as social visionaries and innovators in the world in which these acts took place.”

I could have written an entirely different review of this book, centered on the radical possibilities of movement. Instead I’ll leave you with this:

Joining the chorus encompassed much more than the sequence of steps or the arrangement of dances on the stage of a music hall or the floor of a cabaret. Like the flight from the plantation, the escape from slavery, the migration from the south, the rush into the city, or the stroll down Lenox Avenue, choreography was an art, a practice of moving even when there was nowhere else to go, no place left to run. It was an arrangement of the body to elude capture, an effort to make the uninhabitable livable, to escape the confinement of a four-cornered world, a tight, airless room. Tumult, upheaval, flight—it was the articulation of living free, or at the very least trying to, it was the way to insist I am unavailable for servitude. I refuse it.

Please read this book.

Uranians by Theodore McCombs (Speculative Short Fiction, Astra House, May 30th)

This is a collection of four speculative stories and one novella. The stories are my favorite kind of speculative—weird and upsetting and imaginative and deeply rooted in the injustices and preoccupations of our world. There’s one about a hostile app that is so creepy and smart, and another set in a future San Francisco that’s an incredible exploration of memory, accountability, apathy, shame, and privilege. It gave me chills. I would have loved this collection just for these stories, and then I read the titular novella, and it vaulted this book into the realm of the spectacular. I can’t remember the last time a novella made me cry so hard.

The 100-page novella is set on a spaceship hurtling away from Earth. It’s not a generation ship. The 2,500 member crew, made up of scientists, artists, writers, and philosophers, is heading for Qaf, an Earth-like planet 12.36 lightyears away from the sun. The voyage will take about 80 years. The expedition members have all been dosed with a drug to slow their aging. When they reach Qaf, they will not settle or explore it. Their mission is to look at the planet, tell Earth what they see, and die. What a setup. Of course it’s queer people who sign up.

One of the main characters, Arrigo, describes the ship like this:

From the first published photographs of the Ekphrasis, its hull curving shyly out of earthlight, he knew they were building a queer moon in the heavens—a locus of difference, aberration, exile, a not-Earth. And he knew that Earth would despise them for it.

But this isn’t a story about a spaceship. It’s a story about queer possibility. It’s an incandescent opera of queer liberation, a philosophy of queerness as infinite shapeshifting travel, a thorny ode to world-building, the work of it, the kind we do every day with the people we love and live with. It’s a hard, messy, tangled dream of a queer anti-utopia, a celebration of imperfection, a microcosm of how communities tear and implode and rebuild, an intimate love story, a parenthood story, a queer heartbeat flung out into the cold universe, demanding life, demanding to be heard.

McCombs fills the Ekphrasis with so much queer beauty—wildly outrageous and glorious living decks, extravagant plants, a symbiotic biome full of weird songs and quiet secret spaces. It’s queer brilliance made manifest. But it is not a utopia. The characters build beautiful new ways of being, but they are still defined by old Earth systems. They long to break free, to fling themselves forward into newness, but they can’t. They’re still attached. And their attachment only gets messier as they get further away from Earth, as their dispatches back home take longer and longer, as the people they loved begin to age and die. This question—how do we relate to Earth?—becomes the central driving tension of the novella.

Even as they begin to move away from Earth-thinking, even as their art gets more cosmic, even when they begin having children who are unlike human children, who think and feel and exist as beings born in the stars—nothing gets easier. They still struggle to enact their visions. They get embroiled in the same intrapersonal messes. They hurt each other and fail each other. They default to the punishments and governmental systems they despised on Earth. It’s such a true reflection of communities I have experienced: gritty and honest and not at all romantic.

There’s this through-line about opera (Arrigo is working on a libretto, and records dispatches about his progress to send back to Earth), and while the details sometimes escaped me, I love the way McCombs incorporates art into this story that, to me, feels like a theory of queer beauty, an ekphrasis of queerness at its messiest and most complex:

A long time ago, Leo asked him how queerness propagates, and this is Arrigo’s answer: aesthetically. Our thriving produces beauty and that beauty signals to others that there is life in this way of being. That’s how we persist across generations, by inspiring others into self-honesty. So, it’s important to show Earth that we’re alive: look, it can be done, we got here, we are thriving, we love you, hello. Whatever struggles you’re facing on Earth, look up. Behold.

Queer utopia is impossible, but for me, the Ekphrasis is a queer possibility model. We can’t leave Earth behind. We can’t sever ourselves from ourselves. We can’t burn it all down. But we can keep striving. We can imagine new ways, even if they arise from the tainted ashes of the old ways. The destination is insubstantial, it’s always floating just beyond our grasp. It’s the journey, the process of becoming, that creates realities worth fighting for.

The Bake

Why yes, this week’s bake is once again from Snacking Cakes, because it’s the only cookbook I feel like baking from these days. I like a baking project, but they are too much for me right now, and these cakes are the opposite of too much. Every single one is a put-some-stuff-in-a-bowl-and-mix cake. They are all delicious. If you buy one cookbook because of me, buy this one.

Lemon Currant Cake with Rosemary

My cousin and I both baked this cake over the weekend and they said it was like a scone. I agree! It’s light and not too sweet. I added more zest and rosemary than the recipe called for; it’s easy to play around with.

Ingredients:

For the cake:

Zest from 2 lemons

150 grams (3/4 cup) sugar

2 eggs

110 grams (1/2 cup) sour cream

1 stick (8 Tbs, 113 grams) unsalted butter, melted

1 1/2 Tbs fresh rosemary, finely chopped

1 tsp vanilla

3/4 tsp salt

190 grams (1 1/2 cups) all-purpose flour

110 grams (3/4 cups) currants

1 1/2 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp baking soda

For the glaze (optional):

Juice from 1-2 lemons

100 grams (1 cup) powdered sugar

Preheat the oven to 350. Butter a 9-inch round baking pan, line it with parchment, and butter the parchment. Set aside.

In a large bowl, combine the sugar and lemon zest. Mix with your fingers until moist and fragrant. Add the eggs, and whisk until pale and frothy, about 1 minute. Add the sour cream, melted butter, rosemary, vanilla, and salt. Whisk until smooth. Add the flour, currants, baking powder, and baking soda, and stir with a rubber spatula until combined.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan and smooth the top. Bake for 35-45 minutes, until a tester inserted in the center comes out clean.

To make the glaze: Put the powdered sugar in a bowl. Add the lemon juice a teaspoon at a time, stirring constantly, until you have a smooth, pourable glaze. Turn the cooled cake onto a metal rack and drizzle the glaze on top. Transfer to a plate and serve.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Simple Shrimp & Snow Pea Stir-fry

Even though it’s been years since I was a farmer, I still struggle to buy off-season produce in the winter. It just feels weird. So I end up eating a lot of roots and cauliflower—all delicious—but I get sick of them after a while. The thing is, when I do buy something like snow peas or green beans in the winter, it’s so exciting and revelatory that I don’t want to do it all the time and lose the magic! I made this dish a few weeks ago and I’m still thinking about how perfect it was.

Slice a few carrots into rounds and set aside. Wash some snow peas. Prepare a pound of shrimp however you like to do it—I take the tails off before cooking them—and set aside. Mince 3-5 garlic cloves and grate or finely mince about a tablespoon of ginger. Set aside. Thinly slice a few scallions, and set those aside, too. In a small bowl, combine about 1/3 cup broth (any kind), 2 teaspoons cooking wine or sherry, 1 1/2 teaspoons soy sauce, 1 1/2 teaspoons cornstarch, a scant teaspoon sugar, and a few grinds of pepper. Set aside.

Heat a few tablespoons of neutral oil in a wok or skillet over high heat. Add the carrots and sauté for 3-4 minutes. Add the shrimp and cook until just pink, about 2-3 minutes. Add a bit more oil, the garlic and ginger, the snow peas, and a dash of salt and pepper. Stir fry for another 1-2 minutes. Add the sauce, and cook, stirring constantly, until the sauce has thickened and the shrimp is cooked through. Stir in the scallions and serve over rice.

The Beat: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, read by Alexandra O’Karma

My deep dive into 20th century queer lit has turned into a desire to read all the books on my shelf published before 1950, so I’m starting with Rebecca. I’m about halfway through, and I know Daphne du Maurier is building toward something, but wow is she taking her sweet time! I will say that I was driving home the other night, on the dark and windy road that leads to my house, and I came to a particular scene where Mrs. Danvers the housekeeper is showing the protagonist around Rebecca’s old room. I had to turn it off; it was one of the creepiest scenes I’ve ever listened to. O’Karma made her voice go all cloying, soft, and honey-sweet, and yeah, I turned on every light as soon as I walked in the door.

Also, can we talk about Maxim’s sister Beatrice, queer icon and sporting woman? What kind of straight woman buys her sister-in-law the fanciest, most expensive set of art history books she can find as a wedding present, just because she knows she likes to sketch? A not-straight woman, that’s who. Is Rebecca in the public domain yet? I am dying for a Beatrice-focused retelling.

The Bookshelf

A Portal

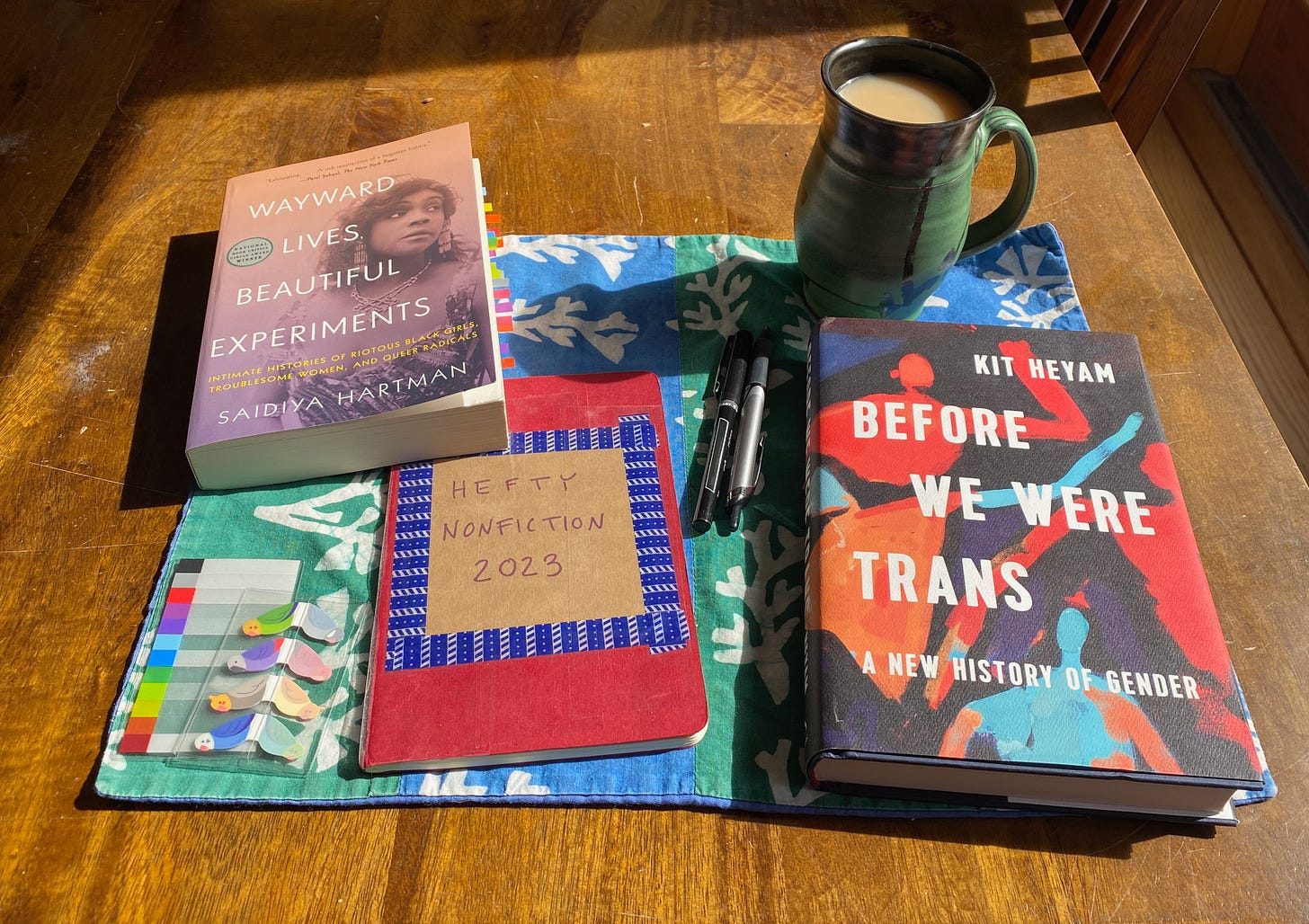

My Hefty Nonfiction 2023 project is going so well! I read (and obviously loved) Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments in February, and now I’m reading Before We Were Trans, which is incredible so far. If you’re interested in reading along with me, just hit reply and I’ll send you the discord link! You can check out the rest of the hefty nonfiction books I plan to read this year here.

And if you’ve already read either of these brilliant books and want to come chat about them in the comments, you know I’m here for it.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I wrote about the joys of having lifelong reading goals and why winter is the best (season for reading). I made a list of some fantastic books by Black authors you might not have heard of; some queer comics and graphic memoirs to add to your 2023 TBR; and the poetry collections I’m most excited about coming out in the next few months. I also wrote an essay about the difference between negative and critical reviews, and my thoughts on both. Plus, I made you a curated queer TBR for March! You’re welcome!

Now Out / Can’t Wait!

Now Out

Something Wild & Wonderful by Anita Kelly: This is a lovely romance set on the Pacific Coast Trail. There is bird content, genuine emotional growth and connection, healing from familial trauma, nature love, and did I mention the bird content?

Can’t Wait!

Flux by Jinwoo Chong (Melville House, March 21): I’m always on the lookout for Weird Queer books, and this sounds weird and great, with time travel, structural experimentation, and WTF moments that coalesce.

Chlorine by Jade Song (William Morrow, March 28): I will read almost anything about water and swimming, and if it’s queer, too—even better.

Queer Your Year

News & Announcements

Thanks to everyone who entered the February raffle, and congrats to Aubrey, who won the Metonymy Press book bundle. Don’t worry, the March prize is awesome, too: a deck of TBR cards made by @jesseonyoutube_! These are so beautiful and creative, and such a fun way to shake up your reading life!

A reminder: if you’ve already received a prize pack, you aren’t eligible for another, but you can absolutely still entire the raffle for TBR cards. I’ll reopen game card submissions the last week in March.

Recs!

Prompt 14: A book set on a continent you don’t live on

Books & Bakes readers are spread across 60 countries on six continents! So here’s one universal rec, a fun sapphic romance set on Antarctica: Rising from Ash by Jax Meyer. And here are some of my favorite queer books set on every other continent:

Asia: Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro; Love in the Big City by Sang Young Park

Australia: Ready When You Are by Gary Lonesborough.

Africa: God’s Children are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu; La Bastarda by Trifonia Melibea Obono.

Europe: The Wrong End of the Telescope by Rabih Alameddine; Fair Play by Tove Jansson.

South America: Cantoras by Carolina de Robertis; Bad Girls by Camila Villada.

North America: Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So; Summer Fun by Jeanne Thornton

Prompt 15: An essay collection

I have read and loved so many queer essay collections! In case you missed it, I reviewed two of my now all-time favorites in last week’s newsletter. Here are a few more:

For essays that are more essays: Making Love with the Land by Joshua Whitehead.

For inventive structures and agile writing about geography, illness, and art: Dark Tourist by Hasanthika Sirisena.

For trans brilliance through the lens of water: Voice of the Fish by Lars Horn.

If you want to read one of my favorite collections: Tomboyland by Melissa Faliveno.

If you love great writing about messy realities: A History of Scars by Laura Lee.

The Boost

Book Giveaways for a Cause are on pause!

I’m pondering the best way to do book giveaways for the rest of the year (additional details about how it works are here if you’re new). Right now, I’m thinking of doing quarterly giveaways—occasional newsletters entirely dedicated to giving away books. I’d list 20-30 books in different genres, and donate all the money to a social justice organization or mutual aid fund. Basically: virtual used book sales for a cause! Would you participate? Let me know below.

Some other things for you:

Erin in the Morning is an incredibly useful newsletter tracking anti-LGBTQ legislation in the U.S. I’m not sure why it has taken me this long to find it. (Apparently she’s a big deal on TikTok, but I cannot venture there.) Erin’s reporting is informative and thoughtful and clear, and even though it is impossible to read without screaming, it’s crucial.

Buy Girl Scout cookies from trans scouts! Check out Erin’s newsletter issue about it, which includes links to buy cookies directly from a bunch of trans scouts. There’s also a Twitter thread.

Some upcoming workshops from Schuyler Bailar.

Erin (@erins_library) has curated an absolutely incredible database of upcoming Indigenous book releases. It includes books coming out this year, but goes back to 2021 as well. I can only imagine the work that went into it. Please tip her if you can!

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: A few months ago, my mom gave me this Christmas cactus, a cutting from one my grandfather had for years. It bloomed! It’s the first time I’ve had one actually bloom. What joy.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! I have no idea what next week’s essay will be about, but if you want to read it, you can subscribe here.

I'm so glad that I read this because I honestly had no idea how bad it was. Thank you!