Greetings, book and treat people! 2024 has been the Year of Poetry for me. I started writing a poem every day in January, and that turned into a world-changing artistic practice that has wildly and joyfully upended my life. I’ve finished some poems and I’ve been sending them out into the world. Two have been accepted for publication next year in a journal I think is pretty rad. It’s hard to explain what this feels like, this small thing, this momentous thing, this beginning of the long work that I hope to be doing for the rest of my life. Things are going to keep falling apart and I’m going to keep trying. For the first time in a long time it feels like I’m on the right road.

I read more poetry this year than I ever have before. I read so much amazing poetry that isn’t even on this list. I have been swimming in it. I’ve been exchanging poems with dear friends and thinking about language and giving my words away to trees to see what shapes they transform into. I’ve spent many days with Mary Oliver (I read 14 of her books this year) and many days with Dionne Brand (I’m almost done with Nomenclature). I am so in love with poetry and this list is just a little bit of that love. I hope you find a new collection or two to sink into in the new year.

Some notes on the list:

It includes the best poetry I read in 2024, not just books published in 2024.

It’s organized by moods and themes.

It includes 25 books, because maximalism. And it could have been longer!

Clicking on a title will bring you to Bookshop. Clicking on linked text in the description will bring you to my review.

The year is not over, so this list is not definitive. For example, I haven’t finished reading Bluff, but it will go on the list when I do. It also doesn’t include rereads (and I reread a lot of incredible poetry this year).

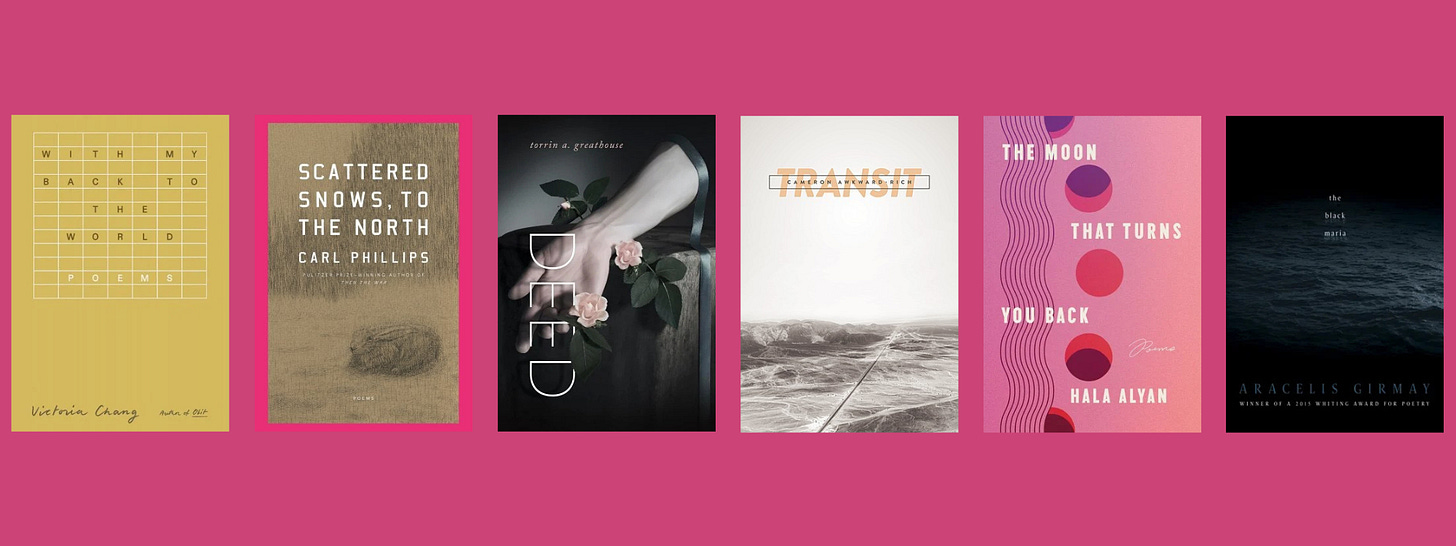

Perfect New-to-Me Books from Favorite Poets

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips (2024): I adore Carl Phillips and it was an honor to review his latest for BookPage: “Phillips beautifully articulates the thorny conflict between reflecting on and being present in: reflecting on time passing while being present in your body; reflecting on the cyclical sameness of human history while being present in the specific ecstasy of a season, a love, a quarrel, the beach at night. The settings of these poems often feel mythological—fields and forests—but they also feel distinctly current.”

Transit by Cameron Awkward-Rich (2015): Awkward-Rich is a magician with words, he moves them in such clear and beautiful ways, every time I read his poems I feel like I’m passing through some kind of water. As in: his work is so clarifying, so light-filled, it cleanses me the way water cleanses me, by showing me bits of truth, pieces of the world, collections of hearts and bodies, strewn about, sometimes deep down, reached for and held through the muck.

The Moon That Turns You Back by Hala Alyan (2024): It turns out I didn’t actually review this beautiful book, I just wrote about how it made me feel. The way Alyan plays with and breaks form is extraordinary.

With My Back to the World by Victoria Chang (2024): This book undid me. It’s (mostly) a series of ekphrastic poems about the paintings of Agnes Martin. I looked at the paintings as I read and felt myself blooming. The poems are about grief and depression and stillness and lines and shapes and language, language, language. Language of trees, crows, lines, stars, grids, time, being a woman, grammar, grief, grief, death, making, shapes, dying, shadows, why. Language of a mind feeling and thinking, whirring, opening and closing, tying and untying, aging, doubting. Stunning.

Deed by torrin a. greathouse (2024): I can’t eat words until I can. We can’t live inside them but we do. Are these poems poems or are they bodies? I wish I was made of language but I’m not. This book is full of knives & blood, scars & stitches. It’s full of what makes & unmakes, unnames & names. The speaker of these poems has a body that aches & loves & refuses to be pieced, to be storied down to number. Here is a body of language, a language of body, all the threads cut and dreamed, ghosted, angered, wilded, fucked, queered, loved & planted back together

The Black Maria by Aracelis Girmay (2016): I cannot write about this collection, cannot write down its vastness, cannot write down the worlds it blooms and breaks. So instead I will write about the sea, the sea that is in every page, every line, the sea that sings and swells these words. The sea endless and the sea now, the sea and its sorrows and its knowing and its names.

The World Cut Open

The Lost Arabs by Omar Sakr (2020): These poems moved me so deeply and hurt so much. Sakr writes about being Arab in Australia and the US, about the violence perpetrated against his people, about what it feels like to be severed from home, about Islamophobia and family and diaspora and queerness and the desire to be both legible and illegible. His words, images, line breaks, phrasing—it’s all visceral and beautiful. There are poems about watching bombs fall and pining for a missing first language in a cab. About growing up in a fraught house. About masculinity and desire. Complicated family lineage is everywhere: he writes about loving the people he comes from while also naming the wounds they gave him.

Coriolis by A. D. Lauren-Abunassar (2023): I felt this book in my bones, the words sitting on my skin. These poems are about grief and displacement, sexual violence and its aftermath, Arab womanhood, invisible Arab womanhood. They are about water and what water holds. They are about the loss of self and the struggle to document that, about endless cycles of becoming and unbecoming. What does a body become when it dies? What does a word become when it’s spoken?

Truthful Odes to Place

From Unincorporated Territory [åmot] by Craig Santos Perez (2023): Åmot means medicine in Chamoru, and this book is full of medicine—and the violence it seeks to heal. The poems are rich with repeated themes. Perez braids contradictions into the poems in devastating, smart, gorgeous ways. Often this braiding is physical. Perez’s poetics is a physical poetics, a poetics of movement and rupture. Over and over again, beautiful songs about ancestral knowledge and thriving native ecosystems are violently interrupted by bald, stark facts about colonization and its continued aftereffects. The interruptions require the reader to move in and out of the physical space of the poem.

Black Pastoral by Ariana Benson (2023): This is a collection of poems about the past, present and future of Black America—how they weave and sing and knock together. It’s about land and the history of the land, which means it is about horror and violence. But it is also full of sites of freedom, acts of freedom. It’s a historical work and a work of imagining and possibility. I’m struggling to express how beautiful and haunting this collection is, how much it stunned me. Benson remakes nature and ecological writing, placing Blackness at the center of both, as it has always been in America, despite violence and erasure.

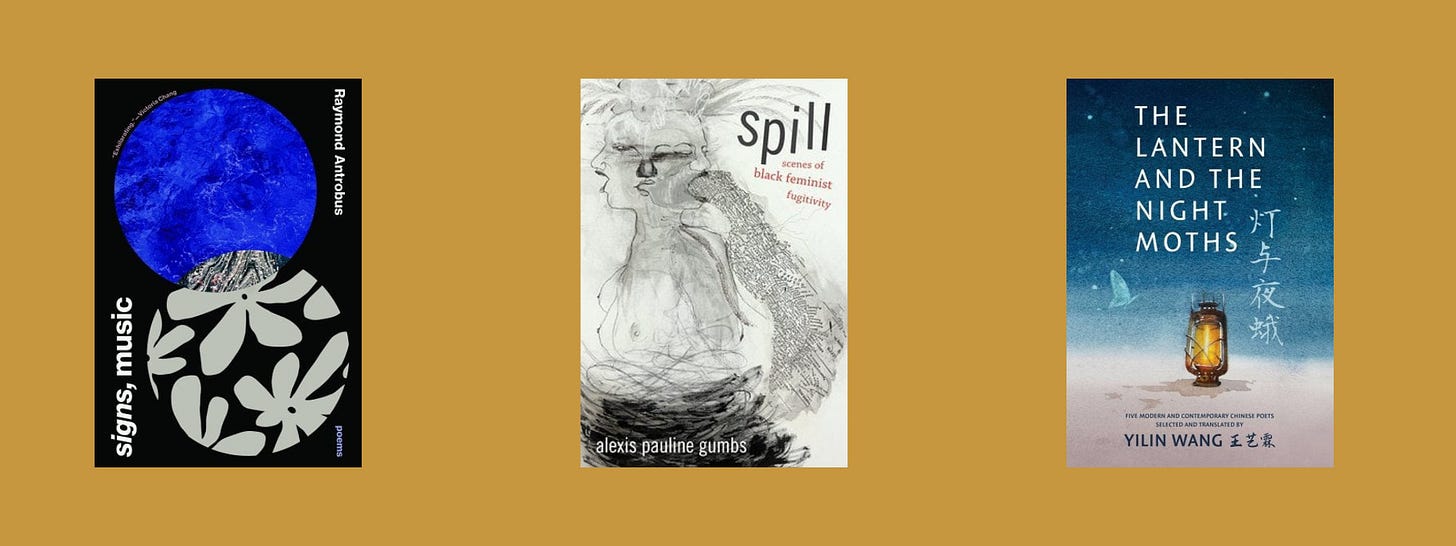

All Poetry is Translation

The Lantern and the Night Moths by Yilin Wang (2024): This is a beautiful book of translations of five modern and contemporary Chinese poets interspersed with essays about poetry and translation. I really enjoyed all five of the Chinese poets Wang translates and presents in this book, especially Qiu Jin, Fei Ming, and Xiao Xi. But the joy here is Wang’s essays about their translation process, and about their relationship to the poets.

Spill by Alexis Pauline Gumbs (2016): These poems are about Black people, Black women, living with and in the entrenched violence of this racist, colonial country—and getting free. They are scenes of freedom. And these scenes of freedom are built with rhymes, flying. How do we imagine newness? How do we imagine ourselves into the next day, and the next? How do we imagine the after of all violence? How do we imagine our way to a different world? Gumbs doesn’t answer these questions, but she carves space, conjures space, weaves space. She makes space for the imagined Black women in these poems to sit and talk. To be whole and loud.

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus (2024): What a beautiful, tender, searching, seeking book. It’s just two long poems, each made up of many sections and forms. The first, Toward Naming, was written during the last six months of Antrobus’s partner’s pregnancy, and the second, The New Father, was written in the first year of his son’s life. Both poems are alive and full of shifting meaning. The sections within them are agile, alighting on a thought or feeling or scene and then flitting away from it. Both poems are grounded in the movement of new parenthood and impending parenthood—time is strange, stretches and quickens. Thoughts fall away and then appear again.

Songs of Queer Bodies

Pig by Sam Sax (2023): These are poems about flesh. They are about pigs, yes, pigs of all kinds: pigs in fiction, the ethos/mythology/associations that many of us have with pigs (the creature, the word), eating pigs, the American meat industry, pork products, cops, leather. But many of the poems are not about pigs exactly—they are about sex and drag and queerness and grief and living in empire. They are about capitalism and its violences and excesses. They are about Jewishness and words and how how we use them and what that has to do with bodies. They are about bodies, broadly: human bodies and creature bodies and where the line between them is. What happens when a body dies, or gets eaten, or becomes a part of the earth. Which bodies get treated like bodies, and which like meat, and what does it mean to treat a body like a body?

Winter of Worship by Kayleb Rae Candrilli (2025): Most things are change and change and change, like the way these poems slip and curl, shapeshift, swallow. Like how the roots of these words have rooted inside me, growing. Roots cut, poisoned, told not to grow. Roots shriveled by loss after loss. Roots still reaching, held by Philly neighborhoods and baseball diamonds, by queer love and trans delight, by true names and true memories. Rotting roots still glittering. Still, the body and its desires, its maps. Still the miracle of choosing a name, loving a song, giving sweetly, being held, still this aliveness shining as it rots, transforms. Transient and planted.

How to Kill a Goat and Other Monsters by Sául Hernández (2024): This is a book of rivers & ghosts. Water flows through it in wave after wave: water and what it takes, what it hides, what it floods. The Rio Grande is everywhere—as the border between the U.S. and Mexico, as a place the speaker returns to again and again in dreams, as a site of loss and violence. In these poems, water floods and destroys, but it also carries family stories, histories, and language. Water sometimes overpowers language and takes control of bodies, but it also transforms, invites.

Language Made, Unmade, Remade

A Theory of Birds by Zaina Alsous (2019): My favorite poetry feels like a place language goes to remake itself. I’m thinking about sci-fi writers who talk about speculative fiction as a tool for imagining different worlds, as a place to go to wield their imaginations, to build things beyond what we know to be possible. I think poetry is that place for language. The best poets understand poetry as a place to do things with language beyond what we know to be possible. The things Alsous does with language are alchemical, botanical, geologic. She breaks syntax, builds new histories with tense, opens doors to infinite possibilities with the spaces she drills into lines, words, sentences, how they touch and do not touch each other.

Aster of Ceremonies by Jjjjjerome Ellis (2023): This book is an ode to plant and human elders and ancestors. It’s full of language play and disability dreaming. I read it in January and I’m still thinking about the ways Ellis breaks and heals language.

Invasive species by Marwa Helal (2019): The things Helal does with form, with language, with the poetics of anger and space, with structure—are incredible. Her ability to expand and distill, the way she contracts so many complicated realities into such short, compact poems, and then the way she expands and expands in the long prose poems—it’s just so powerful and brilliant. The juxtaposition. The aliveness of the forms. I felt these poems light up my brain but they are also heart poems, so deeply about the beating hearts and broken lives and real hurts and endless years and distances that U.S. immigration policy creates.

Customs by Solmaz Sharif (2022): What do we do with language? What do I do with language? What does the state do with language? My people came to this land a long time ago with violence in their fists and used language to steal language. Now their language is in my thumbs, my neck, my eyes. However I try to break it, the breaking will never be enough. Does language return? Does grammar? Can we return grammar to itself, to home? How do we separate all the letters, these tangled syntaxes, these violences stirred together by tense, geography, exile, loss?

Beacons of Light From Other Centuries

She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks by M. NourbeSe Philip (1988): This collection is in a tangle with language. Philip confronts the violence of language and the violence of English specifically. The afterward is a brilliant essay in which she addresses the problem of being a Black Caribbean writer writing in English. She exposes English as a tool of empire, a tool used to kill African languages and also to kill Black people. She names English for what it is: a language deeply tied to the violence of slavery. So what does it mean to be a Caribbean poet, a Black woman, making poems in English? This collection writes into that contradiction, writes into the break, into the place where, maybe—maybe—a new and freer language lives.

Poems of Resistance from Guyana by Martin Carter (1954): I read this slim volume as part of my yearlong slow read of Dionne Brand’s Nomenclature. I’ve been reading books mentioned in the text and/or by authors she’s been influenced by. Carter wrote these poems in 1953 and earlier; the book was published in the UK in 1954 and then in Guyana in 1966 (the year Guyana got independence). Carter is fiery, fierce, passionate, roaring with anger. Several of the poems are structured as letters written from jail. They reference liberation movements around the world. They are about what it means to be a poet in a time of revolution. I did not love every poem in this book, but I was stunned by their passion and immediacy, and most of all by the engine that drives them: love.

Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season by Forough Farrokhzad, tr. Elizabeth T Gray (2022): Oh, this book is so beautiful and true. Long, raw, seeking searching lines. Love poems full of blooms and the moon, gardens and twilight and bodies curling around each other. Such tenderness. Dark, seething poems that name violence so directly, that feel like the speaker rattling bars, thrashing, so angry, so certain, so determined to be free.

An Ordinary Woman by Lucille Clifton (1975): I’ve been thinking a lot about poetic language, about what it means to have one. This collection has a clear and singular poetic language. The poems feel honey and warm and ocean-drenched; they feel like soil and earth, rooted and warm. They’re shapes without sharp edges, they’re all dripping flow and smooth and glide. Roundness, yes, that’s what they feel like—like phases of the moon, waning and waxing, but underneath, always whole.

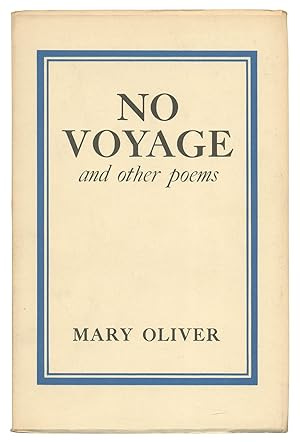

My Heart

No Voyage by Mary Oliver (1965): This is Mary Oliver’s debut, published in 1965 when she was 30. It’s out of print, but maybe your library, like mine, has a copy. I cannot describe the experience of reading it. The poems are almost all formal metrical verse. Many are written in iambic pentameter or tetrameter. Many of them rhyme. Look, I love metrical verse! But these poems feel stuffy, restrained, narrow, like she’s following a set pattern, like there’s something caged in the poems that wants to jump out and can’t. They have no spaciousness. They often include grand declarations, vague moments of unmoored, imageless pathos or sentiment. Much of her later work features these declarations, too, but it always feels earned. You can feel the realness of it in your bones. But these poems feel so stumbling and small, like she was reaching for something she hadn’t found yet.

And yet. The joy of it. What a marvel. To read this book, these dry, imperfect poems, some of which were written when she was 21. To have this record of her becoming. To catch this glimpse of where she came from, to read these lines, these little proofs of change. To know that she did not emerge fully formed, and to get to witness a piece of the long transformation, the transformation that meanings living, loving, grieving, aging—I was not prepared for what holding that beginning in my hands would feel like. Every time I think about this book I feel weepy. It is my least favorite Mary Oliver book (and I’ve read about 2/3 of her oeuvre), and it is the most previous Mary Oliver book I’ve ever read. Reading it profoundly changed me.

Please come talk to me about the best poetry you read this year!

A big surprise to no one, I absolutely love this list and am so excited to read these myself