Greetings, book and treat people. I wrote this newsletter on Monday and now it is Tuesday night. Somewhere I saw a tweet that said: “so much horror, so much hope.” I went to hear Ada Limón read at Smith and she was full of words and joy and wonder. While she was reading this poem, I poem I adore with my whole body, the NYPD was attacking students at Colombia and CUNY. She said something that will live inside me forever: that all poetry deals with the failure of language. That’s why we return to it again and again. So here’s the newsletter.

I’m struggling with language these days. I’m also deeper in language than maybe I’ve ever been. I’m walking around thinking about ghazals and villanelles and it feels absurd and also vital. Students at UMass launched a Gaza Solidarity encampment, so I’ll be looking for ways to support them in the coming weeks. I’ve been thinking a lot about what my parents did in the 1960s, which led me to this article about The Old Mole, an underground newspaper my dad was involved with at Harvard. People on the internet keep talking about how the current wave of student protests against genocide means that older generations have failed, and I find the shallowness of this analysis almost unbearable. Yesterday I watched a video of Angela Davis speaking to students at the University of Colorado. The idea that our elders are failing the younger generation is both insulting and false. Empire is what fails us.

I recently read Hala Alyan’s latest poetry collection, The Moon That Turns You Back. It’s a collection that struggles with and inside language. In a poem titled ‘Spoiler’ she writes: “I’m here to tell you whatever you build will be ruined, so make it beautiful.” I read this line over and over again and the book feels like fire in my hands. The students are building beautiful encampments. They’re making Refaat Alareer memorial libraries, fighting cops with water jugs. Daffodils are blooming in my garden. I’ve called my senators so many times I have their voicemails memorized. In Gaza they’re digging up mass graves. “Nothing can justify why I’m alive. Why there’s still a June.” The other day, two red-bellied woodpeckers at my feeder, their red crests blazing.

The students are building beautiful encampments. They’re praying, dancing dabke. I’m so tired of hearing about the zionists. At Passover everything feels rote. I’m looking for a prayer that’s dayenu but I haven’t found one yet. The daffodils are blooming. In Gaza they’re digging up mass graves. “Losing something is just revising it.” I spend a week writing villanelles and I think there’s liberatory possibility in rhyme, but only when I break out of the poem.

The students are building beautiful encampments. They’re feeding each other, disagreeing. I think about Kai Cheng Thom’s insistence that loving each other can’t mean demanding perfection from each other. “I darken myself with sun and language.” What would have been enough? I haven’t found the prayer.

The students are building beautiful encampments, de-arresting their comrades. I take a poetry workshop with Sarah Ghazal Ali, who speaks about “repetition as a response to the incomprehensible.” I’m haunted by rhyme. I’m haunted by my zionist ancestors, who left Eastern Europe for Palestine before they came to America. What would have been enough. There’s blood everywhere. There’s no blood in my house. In Gaza they’re digging up mass graves.

Every night, a barred owl sings in the woods behind my house. “Was the grief worth the poem? No, / but you don’t interrogate a weed / for what it does with wreckage.” The students are laughing, fucking up. They’re building something. What are we building? In Gaza they’re digging up mass graves. It’s spring and there are daffodils.

The Books

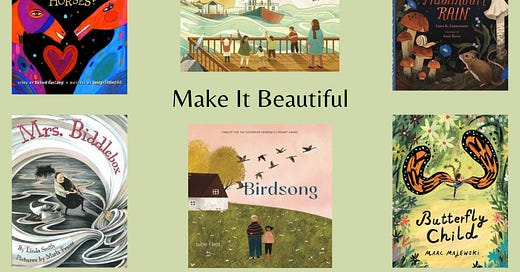

Last week I wrote a guest post for my friend Sarah, who writes Can We Read?, the fabulous newsletter that inspired me to start reading picture books. It was a joy to write and I hope you’ll read it and find some joy in it, too.

So today I’m imitating Sarah and reviewing the six picture books I’ve read in the last week. Picture books for everyone, all the time.

Linda Smith (words) & Marla Frazee (art): Mrs. Biddlebox (2002)

In Indigiqueerness, Joshua Whitehead, speaking about the main character of his novel Jonny Appleseed, says: “I called him "the pain eater" at times. He would take my most traumatic memories and play them out again but do a 180 so they became not hindrances but empowerments for him. He would eat my pain and transform it. Jonny is an avatar of grief.”

Whitehead uses a lot of digestive imagery in Indigiqueerness. He writes about eating, and then transforming, theory. He speaks about art (broadly defined) as one way to digest and metabolize grief. I think about this idea daily. I think about it every time I write or read a poem.

And then I read this book about a woman who metabolizes—literally—her grumps, her grief. It’s been sitting on my kitchen counter since I read it. I look at it every day. I have not been able to get myself to return it to the library. I’ve written before about how picture books have expanded my capacity for wonder, and this book expanded it again. When I finished it, I burst into tears. It’s a masterpiece. Full stop. Not a kidlit masterpiece or a picture book masterpiece. It’s a work of art that will live inside of me forever.

Mrs. Biddlebox wakes up on the wrong side of the bed. She’s extremely grumpy. Everything is bad. Everything is wrong. She opens her door into a sea of simmering darkness. The illustrations are magnificent, by the way. Frazee translates Mrs. Biddlebox’s internal turmoil into weather in ways I’m still untangling. The despair, the wrongness, the sheer “I hate it” of this very bad day seeps out of every page. It’s claustrophobic and incredible.

Anyway, Mrs. Biddlebox decides the only thing to do is to gather up all the badness and bake it into a cake. Here’s what she says:

“I will cook this rotten morning!

I will turn it into cake!

I will fire up my oven!

I will set the day to bake!”

Friends, it gave me shivers. There’s no fixing a bad day. There’s no running from it. There’s no pretending it will get better. Mrs. Biddlebox does not attempt to cheer herself up or look on the bright side of anything. There’s no positivity. She walks into the darkness and bakes it. And then she eats that whole damn cake. She takes the grumpiness and the wrongness and all the bad things into her own body. And the cake is sweet. The cake she makes with the terrible sky and the dreary shadows. It’s sweet. Are you sobbing yet? If that’s not metabolizing grief, I don’t know what is.

I was already all-in, shout-for-the-rest-of-my-life in love with this book by this point, so I’m not really sure how to explain what happened when I read the last three pages, but suffice it to say that my capacity for wonder expanded again. Because after eating her sweet bad day cake, Mrs. Biddlebox simply climbs the stairs to her bedroom, welcomes in the night, and goes to sleep. She doesn’t get her day back. She doesn’t say, “well, that wasn’t so bad after all, was it?” Something shifts; something has been transformed. But it’s not the bad day.

What happens in the artwork in these last few pages is extraordinary. The only other picture book I’ve read (to date) that uses light and color in this way is The Longest Night. I gasped when I turned the final page in that book, and I gasped when I turned the final page in this one. Something starry and huge lit up inside me.

Look. You can read this book another way. You can read it as a funny, charming story about an eccentric old lady who wakes up grumpy, bakes her grumpiness into a cake, eats it, and feels better. It’s relatable, it rhymes, it’s witchy, there’s a dash of magic, Mrs. Biddlebox’s facial expressions are delightful. Yes, and. Books—oh, miraculous!—can be more than one thing. Perhaps this is the biggest miracle of all. Wonder, indeed.

Here is Sarah’s review!

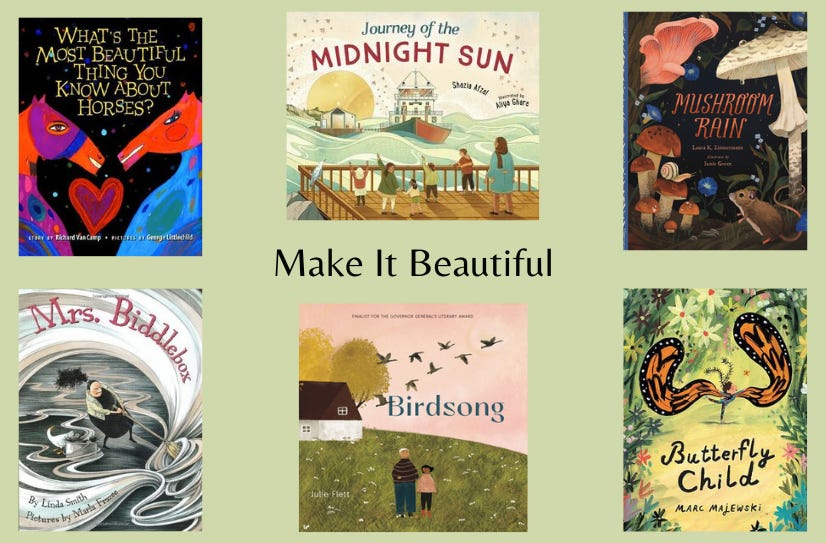

Laura K. Zimmermann (words) & Jamie Green (art): Mushroom Rain (2022)

First of all, the illustrations in this are gorgeous. There are so many different kinds of mushrooms, and they’re all so beautiful and detailed. Mushrooms are so magical and strange! Green captures this so well. Every page is filled with glorious mushrooms in different habitats and weather.

The text is simple. It describes how mushrooms grow and bloom. I’m really into nonfiction picture books like this that aren’t involved or complicated, that are…wonder-forward. This is not a primer on fungal networks—it’s a primer on how wild and amazing the natural world is. That said, this book also includes some extensive back matter that I learned a lot from. I know almost nothing about how clouds form (from seeds—things like dust and mushrooms spores—that collect water). I mean, I know the basics, but I did not know there were mushroom spores in the sky! Love.

Also: mushroom rain is a translation of a phrase in Russian that means something like: a light rain that falls while the sun is shining. This, apparently, is good mushroom weather. What a cool detail.

Shazia Afzal (words) & Aliya Ghare (art): Journey of the Midnight Sun (2022)

This is a fascinating book about a small Muslim community in Inuvik, located in the far north of Canada inside the Arctic Circle. When an organization in Winnipeg learned that this community was worshiping in a trailer far too small for them, they decided to build a mosque and send it, by truck, to Inuvik—a distance of about 2,770 miles.

The book reads a bit like an adventure story. The mosque encounters all sorts of difficulties along the way. Sometimes it’s too wide for certain roads. In one case a bridge has to be fortified so it can get across. Folks help out by taking down signs, lifting power lines, and sharing the road. Eventually the mosque makes it to the Hay River and gets a spot on the last barge to Inuvik before the winter.

I had never heard of the Midnight Sun Mosque, which is one reason I love picture books: here’s this neat thing that happened, and it moved someone enough that they decided to write a book about it. The illustrations of the community setting up their new mosque, filling it with books and prayer rugs, and then feasting and celebrating in its big, open room—are so beautiful. This is a warm and simple book about people coming together in unexpected ways. It’s also, delightfully, about the logistics of moving a massive object, which I found equally satisfying.

Julie Flett: Birdsong (2019)

I am slowly working my way through all of Julie Flett’s books, which are all gorgeous. This one is about a young Cree girl, Katherena, who moves to a new house in the country, far away from the city by the sea she’s always lived in. She’s lonely and unsure about her new home, until she meets her neighbor, Agnes. Agnes is an older woman who loves working in her garden and making ceramics.

Over the spring and summer and fall and winter, Katherena visits Agnes again and again and again. They share stories and moments as the seasons turn. I love the sparseness of this story. It’s so quiet. There aren’t a lot of words. But the beautiful simplicity of the illustrations radiates love. I felt Agnes and Katherena’s friendship in my bones as I was reading, even though I only witnessed a sliver of it.

A year after they meet (and this is another thing I adore about this book—so much time passes in such a subtle way), Agnes has become too sick to go outside. So Katherena brings the outside to her in a gesture that filled me with sadness and sweetness. Agnes tells her this gift is like “a poem for her heart” and that’s what this book feels like, too. I am walking around in a constant state of grief and wonder these days, and Flett captures how deeply those feelings are intertwined.

Marc Majewski: Butterfly Child (2022)

Oh, I adored this book. It’s exuberant and beautiful and bursting with flowers. On the first page, a kid declares “I am a butterfly!" in a room surrounded by their butterfly artwork. They burst out of their house wearing their huge butterfly wings and flowery antenna, and they’re off: to twirl and dance and jump and be free, letting the wind carry them from flower to flower. The artwork is breathtaking, full of so much vibrant color.

There’s a whole story arc about a group of kids who bully them for their self-expression that is just so good, so subtle and carefully written. The kid runs back home in anger and despair and their dad is there for them. Their dad seems them. Sits with them. Brings them some pie. I found this whole sequence almost unbearably moving. I think this is because the dad’s actions are so concrete, and they’re mostly expressed through artwork. There’s no big lesson, no lecture. This kid is really upset, and their dad gives them space to be upset. Then, eventually, he helps them make their wings again. It all feels so routine, so ordinary, these actions of care, this expression of love.

The ending is perfect. I won’t spoil anything, but I teared up on the last page. Also: the dog in this book is hilarious, and where can I get a butterfly antenna helmet made with a fork and a spoon?

Richard Van Camp (words) & George Littlechild (art): What’s the Most Beautiful Thing You Know About Horses? (1998)

This book feels like it was written for me. It feels like a poem. It’s 40 below in Richard Van Camp’s hometown of Fort Smith, Canada. There are no horses around and his people, who belong to the Dogrib Nation, are not horse people anyway. Van Camp says that he’s “a stranger to horses and horses are strangers to me.” But he decides he wants to know all about horses anyway. He has some questions for horses, such as: Do they have secrets? Do they love? “Do horses think fireworks are strange flowers blooming in the sky?” He can’t ask horses, so he decides instead to ask his friends and family: “What’s the most beautiful thing you know about horses?”

I cannot explain how strange, how poetically nonsensical, how gorgeous this book is. Who comes up with a question like this? Yet Van Camp treats it like the most obvious question in the world. If you’re not asking the people in your life what’s the most beautiful thing they know about horses, then what are you doing? Are you even paying attention? Are you thinking about how big and hurting and glorious this world is? Are you living curiously? His tone is so matter-of-fact, so interested, so excited, so ordinary. It makes magic out of this one question. It makes this one question into a question about so much more than horses. (Though some of the responses he gets about horses are quite beautiful.)

At the end of the book, after he’s shared all these beautiful things about horses, he writes: “Here are some secrets I learned the last time it was this cold. I learned that an eagle has three shadows. I learned that frogs are the keepers of the rain. I learned that there’s an animal on this earth who knows your secret name.”

I mean! What? I cannot get over these poetic leaps. This book is everything I love about poetry in one exuberant conversation about horses. And I haven’t even mentioned the art, which is messy and colorful and exactly right, full of its own visual leaps. Magic.

This is another one I’m pretty sure I read because of Sarah but I can’t find her review!

And Beauty

Some things I care about:

Through May 4th, all contributions made through the Great Falls Books Through Bars wishlist are being matched. Check it out and buy a book or two.

Earlier this year, Small Press Distribution suddenly went out of business, leaving hundreds of presses scrambling to stay alive. So many presses I love are struggling. One of those is Little PussPress, an indie press run by trans women. They are doing a Kickstarter with some fantastic rewards. They are very funny. I love their books! Please support them if you can.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Here is another daffodil.

Catch you next week, bookish friends. In the meantime, if you want to fill up the comments with whatever’s bringing you hope, keeping you going, feeding your softness and your steadfastness and your fierce love—well, I’d love to hear about it.

"The idea that our elders are failing the younger generation is both insulting and false." Like the mole in that Harvard countercultural publication you cite, much about our world is "underground" and not immediately visible. I'm reminded of one of the themes of "Cloud Atlas," which covers six stories across 600 years, and where the resistance movements of each generation, although not outwardly "successful," sow the seeds for those that are to come. Abolitionist and justice movements of today have the oft-quiet and sometimes-deafening work of past generations to thank for their continued existence.

Just wanted to share I found this particular piece very moving. Thank you for sharing. Your words are giving me a lot of hope! The communities being built on campuses give me hope. I'm finding softness in a regular bedtime and routine. Thank you for creating this community Laura.