Greetings, book and treat devourers! I decided to take a social media break this week and it’s been so lovely and quiet. I genuinely love the tiny corner of social media I inhabit—queer Bookstagram—and I’ve made some connections there I cherish. But it can be a lot sometimes, the scrolling. And breaks are healthy.

In other news, I helped my dear friend plant some peach trees on her land over the weekend, and it inspired me to actually do a little gardening at my house! Friends, I am excited about spring, truly. It’s a wonderful feeling.

This week’s three books could not be more different from each other. I loved them all. I think I’ll let them speak for themselves.

The Books

Backlist: Summers Sons by Lee Mandelo (Fiction, 2021)

I’ll be honest: this is one of those books that felt like it was written for me. It rocketed straight into my heart, haunting and beautiful and devastating and hopeful. This is the kind of book I find hardest to review, because I just want to clutch it to my chest, keep it close.

This is a story about the pain of hiding yourself, of how hard it can be to see yourself, of how long it can take certain wounds to unwind and untangle and scar over. It’s about how easy the world makes it for queer people—especially for queer people who do not love the way we’re taught you’re supposed to love, for queer people whose families and desires and hearts do not look like the families and desires and hearts we see all over the media—to move through life in an easy but choking haze, to avoid softening, opening, speaking, reaching out, letting themselves be seen and cherished.

It’s also a story about healing, about what it takes to step out of that choking haze. It’s about patience and persistence and the kind of found family and relentless friendship that creates space, that makes room for a person to step into themselves, messy and wanting and imperfect and loud.

And it’s a story about ghosts, literal and metaphorical, about what haunts us and what we don’t allow to haunt us, about the memories that live under our skin and the stories that shape our breath. It’s about the weight of what we carry and the gleeful, raucous joy of releasing that weight. It’s about all the forms grief takes, and the work—real, physical, exhausting work—of transforming and living with grief.

Andrew is a twenty-something grad student who’s just arrived at Vanderbilt University. He was supposed to be there with his lifelong best friend Eddie, but Eddie died, apparently by suicide, just before Andrew arrived. Andrew is certain Eddie didn’t kill himself, and he’s determined to find out what happened. He and Eddie were in love, though they never admitted it to each other, and so his grief is complicated by everything they never said. He and Eddie also shared a unique ability to see ghosts, something they’ve kept a secret between them since they were kids.

Andrew has never shown himself to anyone but Eddie. Now he’s living in the house Eddie left to him, with a roommate he doesn’t know, a man who seems to know more about Eddie than Andrew ever did. So when he tentatively begins to show himself to his roommate, and even more gently and tentatively fall in love with his roommate’s cousin—it explodes his world. These men invite him into their family—slowly, repeatedly, again and again and again until Andrew starts to believe he deserves to be loved. They are rough and messy and loud and inelegant and exude the kind of dangerous masculinity that Andrew has been hiding behind his whole life. There’s a lot of drugs, and fast cars, and extremely bad decisions, and punches thrown. But underneath, Andrew finds tenderness, and fierce loyalty, and people who are willing to see him and hold him—haunts and breaks and mistakes and yearnings and regrets and all.

There’s a lot more I could say about this book. It’s dark and atmospheric and strange. It’s full of layers. Andrew’s coming into self and family is the main event, but there’s also a lot here about racism in academia, and the legacies of slavery in the South, and what it means to be connected to a particular place and piece of land. It’s romance as healing, and ghosts as potent reminders of what we don’t talk about, what we need to talk about. It’s queerness like a river, an electric current, something buried deep longing for light. It’s slow, painfully slow, the way life is slow. It has a perfect ending.

Frontlist: The Sex Lives of African Women by Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah (Nonfiction)

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah is a Ghanian writer, activist, and Pan-African feminist. She co-founded the blog Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women, out of which this book grew. Between 2015 and 2020, she interviewed dozens of African women from across the continent and the global African Diaspora about sex, sexuality, relationships, family, and intimacy. Over thirty of those interviews, with women from twenty-one countries, and ranging in age from 21 to 71, are collected in this book.

I love how diverse and inclusive this collection is. It includes stories from queer and trans women, single women, married women, monogamous and non-monogamous women. So many sexualities, cultures, ages, philosophies, religions, and experiences of sex are represented. Some interviews focus on specific relationships, or specific sexual experiences. In some, women speak more broadly about their journeys, both healing and painful, around sexual identity. Each one is different.

Sekyiamah is a fantastic guide through all of these different stories. The book is conversational, with a wonderful unpolished style that makes it feel not like you’re reading a book of interviews, but like you’re sitting down with a friend, and she’s telling you what’s her mind. Though the book is broken into three sections (Self-Discovery, Freedom, and Healing), Sekyiamah doesn’t provide any commentary or analysis. She doesn’t draw connections between the experiences of the women she interviews. There’s no “aha!” moment. It’s a book of stories—about pleasure, marriage, queerness, familial expectations, desire, polyamory, motherhood, heartbreak, abuse, shame, self-discovery.

This lack of any overarching narrative is what makes the book so compelling. Sometimes stories are worth telling simply for their own sake. A lot of the interviews end abruptly. The women speak about what’s happened to them, what’s happening to them, where they are. Some of them are in happy, healthy relationships. Some are just getting over a heartbreak. Some are lonely. Some are in the middle of some kind of turmoil. Sekyiamah presents the interviews as they are, with resolution if there is resolution, and without it if there isn’t any. Life is messy. Sex is complicated for most people. And so this book isn’t neat or easy. It’s joyful, funny, contradictory, confusing, and painful.

Upcoming: Bad Girls by Camila Villada, translated by Kit Maude (Fiction, Other Press, May 10th)

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about bleak books, particularly books with a lot of queer suffering, and why sometimes they work for me and sometimes they don't. A lot of it has to do with my mood and expectations—I can’t handle tragic surprises, especially when it comes to queer characters dying. But the bigger piece of it has to do with how stories are framed. I can’t stomach books that utilize the straight gaze anymore, books that exploit queer lives for lessons. But I can read sad stories told from the inside, stories that honor the queer people telling them, stories that don’t flinch away from pain but don't reduce characters to their suffering.

Bad Girls is one of those books. It’s a bleak read with a deeply sad and upsetting ending. It’s a lot darker than most of the books I recommend here. There’s a lot of transphobic violence in it, including the murders of trans women, as well as rape, sexual assault, and suicide. About halfway through, when I realized there was no way it would have a happy ending, I steeled myself. Still, I almost didn’t include it here. But I loved this sad fierce song of a book. I can’t stop thinking about it. The characters live in my heart now. If you’re up for something hard, this novel has a lot to offer.

The story revolves around a group of travestis living in Córdoba, Argentina. In the author’s note that precedes the book, Villada explains why she uses the word travesti, and not something more familiar to English-speaking readers, i.e. trans women:

Far below, where the secret rivers of the world flow, appeared a word that stank of death, shit, semen, prostitution, the night, the cold, bribery, blood and jail, of misery and neglect. A word sharp as a knife, grime-encrusted and wounding. A word that spoke not just of the creatures we were and are, but also of our poverty, of the acts that made us legendary, of the courage with which we headed out to live among families and communities. Ww didn’t want to look like women, we didn’t want to hide our struggles in any way, we didn’t feel trapped in the wrong bodies, we didn’t know what we were doing.

And so, I don’t use the term trans women, I don’t use surgical vocabulary, cold as a scapel, because the terminology doesn’t refelct our experiences as travestis in these regions, from indigenous times to this nonsense of a civilization. I reclaim the stonings and spittings, I reclaim the scorn. You may ask how it can be that a writer proudly identifies herself with an insult. My answer is that you’re looking for the way out up there, where you think your thoughts are formed. So elevated, useful, and precise. We, after years and years of holding back the travails of Latin America with our bodies, know that you have to delve deep, go down, learn from other creatures who treasure their ignorance of themselves. We know it’s better to escape through tunnels than try to leap over walls.

I know that’s a long passage to quote, but it gives you a better sense of this book than anything I could write. The narrator is a twenty-year old travesti named Camilla who leaves her small town to attend university, and finds a family among the travestis of the city. These women are mostly sex workers, and many of them live in a communal house owned by Auntie Encarna, a 178-year old travesti and the mother of this complicated, messy, constantly shifting family of women and girls.

There’s not a lot of plot; the book is a manifesto, a witness, a coming-of-age rant. Early on, Auntie Encarna finds an abandoned baby in the park where the travestis work, and decides to raise him as her own. The baby, whom she names Twinkle in her Eye, changes the dynamic in the household. Some of the travestis take to him; others resent him. Some move in; others move out. Camilla observes it all, sharing her own coming-into-self story, and the stories of many of her sisters: how they live and how they die.

It’s not a safe book. Camilla is not interested in assimilation, in making herself or the people she loves legible to the cis, straight world. None of the characters are good. They’re funny and caring. They’re mean and petty. They support each other and let each other down. Camilla tells it like it is. Sometimes how it is is family and community and the deep ease of being seen and known and cared for. Sometimes how it is is desperately trying to survive the violent, transphobic world. And not everyone survives that world. This is why the suffering in the book felt bearable to me. Well—not bearable. It’s heartbreaking and enraging and at times I had to stop reading because it was too much. But the suffering doesn’t serve some greater purpose. It’s not sensational. Nobody learns anything from it. It’s part of Camilla’s world, and Camilla is determined to get her world right, to tell it truthfully, all the muck and beauty and rage and hilarity and pain of it.

There’s also a lot of softness, and tenderness, and patient, unconditional care. In one scene, after one of the travestis is assaulted, another woman performs a healing ritual on her. After she’s done, Camilla describes the scene:

What was left was the magic of travestis: cleaning the wounds with a cloth and warm water, swaddling her in blankets, doing her hair, and singing quietly. A very mundane kind of magic. The kind anyone might work, but seldom does.

In another beautiful passage, when the travestis find out that one of them has been admitted to the hospital due to AIDS, Camilla writes:

And so the whole travesti sisterhood mobilized. The music of our heels walking up the hospital steps, the tinkling of our jewelry, seemed, just for a moment, capable of redeeming the world.

Despite all of the violence that Camilla and her family face, and despite the gut punch ending, this book reads like a love letter. At one point, when Camilla is telling the life story of one of her friends, Angie, she writes:

The first words I heard come out of Angie’s mouth were “I became a travesti because being a travesti is a celebration.”

It’s out May 10th and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

I didn’t actually make it to a seder last week, but I did make some Passover cookies! These cookies are so easy. I repeat: SO EASY. You take some stuff, put it in a food processor, pipe the batter onto baking sheets, done. I highly recommend sandwiching them with a quick chocolate ganache, but they’ll still be delicious—and even easier—if you don't.

Chewy Raspberry Amaretti Cookies

Adapted from Smitten Kitchen

I’ve been making these cookies for years and I’m still not tired of them. The only small change I make to the original recipe is the addition of freeze-dried raspberries. The almond-raspberry-chocolate combination is perfect. But if you don’t have freeze-dried raspberries or prefer a more almondy cookie, feel free to leave it out.

Ingredients

For the cookies:

15 grams (about 5 Tbs) freeze-dried raspberries

200 grams (one 7 ounce tube) almond paste

150 grams (3/4 cup) sugar

2 egg whites

pinch of salt

For the ganache:

100 grams bittersweet chocolate, chopped

100 grams (about 1/2 cup) cream

Make the cookies: Preheat the oven to 300. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper or silicone baking mats.

Grind the raspberries in a food processor until they turn into a fine, crumbly powder. Add the almond paste and sugar and pulse several times to break up the mixture. Add the egg whites and salt and blend until smooth.

Transfer the mixture to a piping bag or a ziplock bag. Snip off the corner, and pipe small rounds, about 3/4-inch in diameter, onto the prepared trays. Leave about an inch between the cookies.

Bake for 15-20 minutes, until puffed and slightly golden. Allow to cool completely on the trays before gently removing them.

Make the ganache: Place the chocolate in a heatproof bowl. Heat the cream over medium low heat until hot but not scalding. Pour the warm cream over the chocolate and whisk until it becomes thick and shiny. Let cool about 15 minutes before using.

Assemble the cookies: Turn half the cookies upside-down. Place a dollop of ganache in the center of each, place another cookie on top, and press down to sandwich. Let sit at room temperature for an hour or so to let the ganache firm up before eating.

I don’t know how long they last because I ate the whole batch (with a little help) in a weekend. My best guess is 3-5 days.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: One Pan Shrimp and Chorizo Pasta

I made a version of this, courtesy of the NYT cooking app, a few years ago, and it’s become one of my go-to quick dinners. It’s easy to alter based on what I have around, and it comes together surprisingly fast for something so filling and delicious.

Finely chop an onion. Heat a few tablespoons (at least) of olive oil in a large Dutch oven or similarly-sized pan. Add the onion, some salt and pepper, and several pressed or minced garlic cloves and cook for a few minutes. Break up a package of angel hair or other thin pasta into small pieces, and add that to the pan. It’ll be a little messy and some pasta might go flying. It’s okay, keep stirring over medium heat until the pasta starts to turn golden. Add 4-5 Tbs of harissa (I usually use tomato paste, but this time I didn’t have any—harissa is delicious in this!), a pound of chorizo (links or ground, either sliced or broken up), and a quart of stock (whatever kind you have, water is okay too). If you have fennel, it’s delicious here; I didn’t have any.

Bring to a boil, cover, and then simmer over medium heat until the pasta is tender and has absorbed most of the liquid. Stir in some shrimp (a pound or so), a whole lot of grated parmesan, the juice of 1-2 lemons, and a few handfuls of chopped parsley. Continue cooking until the shrimp turns pink. Serve with more Parmesan, lemon wedges, and more chopped parsley, if you want. Yum!

The Beat: Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades, read by Tashi Thomas

I have so many audiobooks saved in so many different apps—probably hundreds. I’m often overwhelmed with choice when I go to pick a new book. I just want to read them all! Right now! This morning, Brown Girls won out over Nightbitch, Matrix, A Marvellous Light, and Know My Name. If you’ve read and loved any of these, please come tell me about it! I need some serious audiobook-choosing help.

Anyway, I’m enjoying Brown Girls so far. It feels more like poetry than prose to me, which is interesting, because I know it’s not written in verse. Maybe it’s partly because Tashi Thomas has a lovely, lyrical way of reading. It reminds me a lot of Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming—not so much because of the content, but because of the style. It’s a series of vignettes about a group of brown girls living in Queens—very descriptive and detailed but without much plot.

The Bookshelf

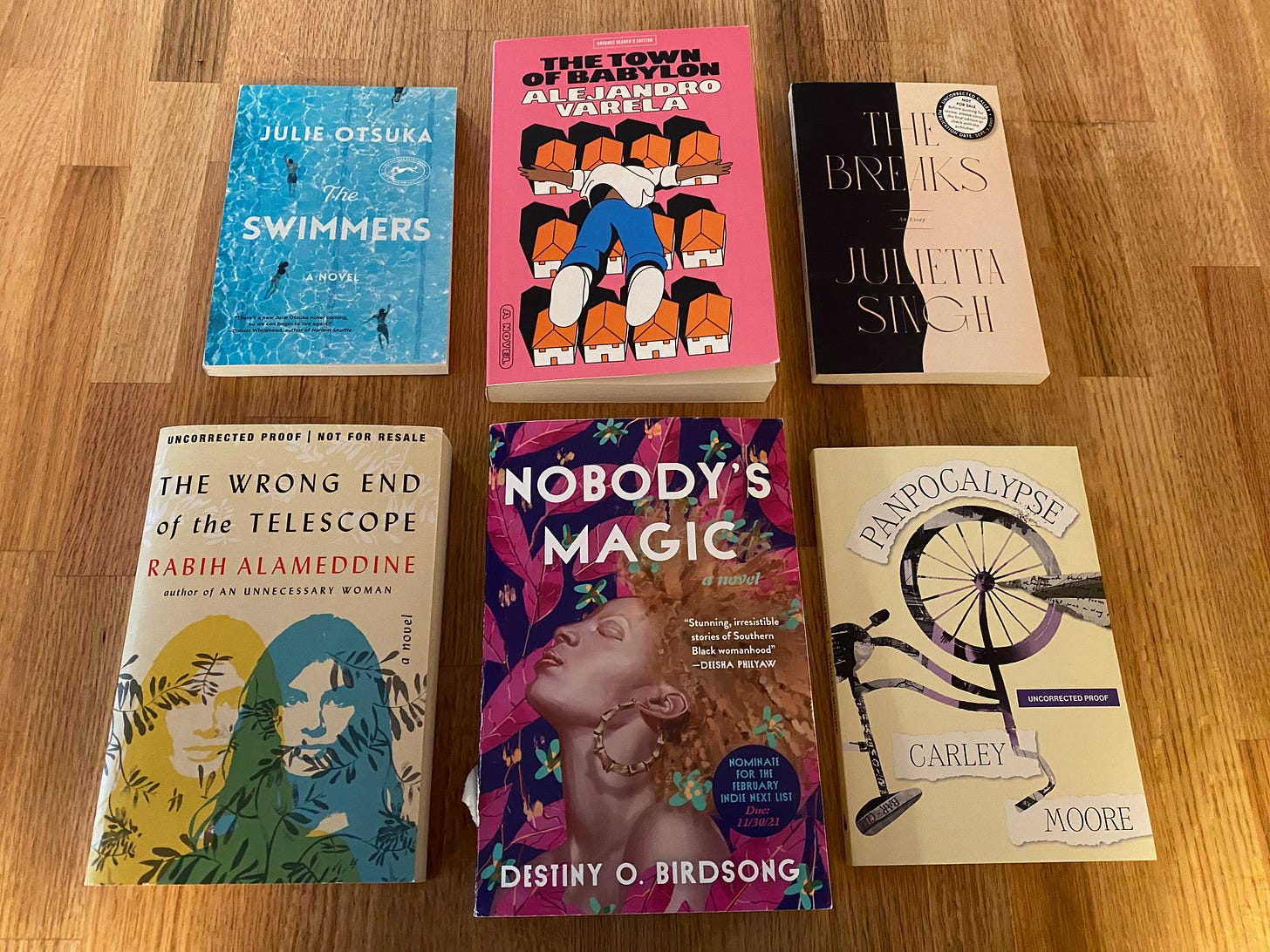

A Picture

I’ve ended up with multiple copies of a few ARCs, and I’d love to pass the duplicates along to other readers! I absolutely loved every one of these books. Leave a comment letting me know which one(s) you’re interested in, and I’ll randomly select a winner to receive each book.

Books available: Panpocalypse by Carley Moore, The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka, The Town of Babylon by Alejandro Varela, The Wrong End of the Telescope by Rabih Alameddine, Nobody’s Magic by Destiny O. Birdsong, and The Breaks by Julietta Singh.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I made a list of ten nonfiction books I’d love to see adapted into comics.

Bonus Recs Featuring Found Families Across the World

I recently enjoyed Ready When You Are by Gary Lonesborough, a lovely queer YA novel about two Aboriginal teenagers. I had mixed feelings about Here Again Now by Okechukwu Nzelu, but I did appreciate parts of it, especially how Nzelu explores the overlap between found families and bio families. Heaven by Emerson Whitney is a fascinating book about family in many forms. And when it comes to romance about found families, I will never stop talking up one of my favorite queer historicals, Behind These Doors by Jude Lucens.

The Boost

A local fundraiser close to my heart: Rosendo Santizo is an immigrant farmer raising funds to help him purchase Winter Moon Roots, the farm he’s been working on since 2010, and managing since 2018. As Rosendo says:

The farming industry is predominantly white-led and has deep ties to inherited land and wealth. The process of shifting my role from a worker to an owner requires an immense amount of resources that are not readily available to immigrants and people of color. We are the backbone of local farms through the labor we provide, but we rarely own the means of production.

You can donate here. Email me a screenshot of your donation and I’ll match donations up to $100!

I enjoy Sonia Feldman’s newsletter, Sonia’s Poem of the Week. Every Friday, she sends out a poem, usually with a bit of commentary. Sometimes I’m not in the right headspace to engage with the poems, but sometimes they hit me right in the heart. Last week’s was one of those.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Last summer a friend and I started a weekly tea by the river tradition, and a few days ago we had our first riverside tea of 2022. It was pure magic.

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

I am interested in Panpocalypse by Carley Moore. Love reading your newsletter!

I'd love a chance at The Swimmers, too!