Volume 1, No. 9: Magical Collaborations + Tahini Halvah Brownies

Greetings, book and treat people! For those of you who are here for the introductory bird content, I have a pair of rose-breasted grosbeaks frequenting my feeder! I saw the female first, and was in the middle of texting my brother (and birding mentor) for help identifying it when I figured it out myself (thanks, internet). A few hours later I saw the male. The females are brown with mottled breasts and a white stripe on their heads — not nearly as striking as the males, but I love them.

My brother also pointed out that they have a beautiful song: “very cheery and bubbly, like a really excited and happy robin”. I haven’t heard my resident pair sing yet, but I’m looking forward to it. By the way, my brother is an amazing bird photographer — if you enjoy these little bird updates, check out his work!

Anyway, I’m here to talk about books. Specifically, the magic that happens when people collaborate on a book. This week’s books feature collaborations between author and translator, between many authors, between artists and poets. In all cases, the result is something new and unexpected, a book one person alone could not have made. In fact, seventy-four different people contributed to the beauty that is these books. Think about that for a minute!

The Books

Backlist: The Tree and the Vine by Dola de Jong, translated by Kristen Gehrman (fiction, 1954, English translation 2020)

For a brief moment, after finishing this novel, I was overcome with the familiar exhaustion that often accompanies reading a tragic queer story. But as I let de Jong’s words sink in, I realized what I was actually feeling was a specific sadness related to this particular book and its two main characters.

Then I read the translator’s note. Dola de Jong was born in the Netherlands to a Jewish father and a German mother. She fled the country in 1940 and spent most of her life in the US. The Tree and the Vine was published in Dutch in 1954 and first translated into English in 1961. Kristen Gehrman’s translation is new. Here’s something she said that resonated with me:

It's easy to look at this story through the lens of war or to see it as a lesbian romance that could never be because of the restrictions of the time. But as I got to know Erica and Bea better, I came to see their restlessness, struggles, doubts, and hesitations as reflective of a broader female experience. The Tree and the Vine is one of the richest texts I've had the pleasure of translating and one that will stay with me.

Gehrman also quotes Marnix Gijsen, a writer who championed the original publication of the novel in 1954, despite outcries from publishers. He said: it is "an important and remarkable book — and not because it addresses a delicate problem with so much understanding, that's just the starting point. I'm more in awe of the finesse with which Dola de Jong sketches her two main characters."

Both Gerhrman and Gijsen articulated my own feelings better than I ever could. My brain wanted to protest — not another lesbian tragedy — but my heart knew this book was something different.

The novel takes place in Amsterdam in 1938-1940. Bea and Erica meet at a mutual friend's house and move in together soon after. The novel charts their volatile relationship. Bea becomes obsessed with Erica, but can't or won’t admit it. Erica, meanwhile, is much more open. She has affairs with women and flits around Europe. She’s Jewish, and seemingly fearless, despite the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam.

Bea recounts these events from some point in the future. The writing is lovely, sharp and simple. Bea captures the intensity of her relationship with Erica, but her distance from it allows her to see what she couldn’t then. And though much of the novel is concerned with the ordinary — buying furniture, going to work, worrying over money — there’s a frenetic energy to it. I read it in one sitting.

As Gerhrman and Gijsen point out, the power of this novel is in the richness of de Jong’s characters. Passing it off as another tired lesbian tragedy takes away their agency, their quirks, their particular emotional hangups, their desires and histories. This isn’t a simple sad story. It’s a complicated human one.

Erica is selfish, reckless, courageous. She rarely thinks of anyone other than herself. She’s prone to angry outbursts. She relies on Bea but often doesn’t listen to her. On vacation in Paris with Bea, she has an affair with an American woman, who then becomes her whole world. Here’s Bea describing it:

Within an hour of meeting, Erica and Judy were walking hand in hand or with their arms around each other. I couldn't believe it, but I just plodded along behind them. Their friendship was short but intense. The break-up came before dinner with such a vulgar dispute that even the Parisian passersby stopped to watch. After a "drop dead!" from Judy and an expletive from Erica, we parted ways.

This passage captures so much of Erica's character: her intensity, her brazenness, her volume, her impulsiveness. Bea, on the other hand, is cautious. She likes solitude. She enjoys her comfortable, ordered, easy life. It’s obvious why she and Erica clash so often, why Bea struggles to let loose in the way Erica wants her to.

While visiting a museum alone, Bea muses: "I was overcome by a strange sense of loneliness. I thought of Erica, missed her even, though this feeling bothered me and I tried to suppress it." She’s constantly making observations like this. She’s aware of her own reluctance to admit her love for Erica, and she’s fighting herself on it. Her careful, direct narration is the opposite of Erica's whirlwind way of life. That’s where the tension comes from, that’s what makes this book so good. Their relationship falls apart because of who they are. Of course the war is also a factor. So is the time they live in. You can't take people out of context. But treating the context as the only thing that matters, assuming that what happened to them only happened because of where and when they lived — that erases their humanness, a humanness that de Jong so beautifully writes into existence.

All translations are collaborations. I include this one here not only because of that, but to acknowledge how deeply Gerhrman’s reading of it affected my own. I believe I would have loved this novel if I hadn’t read her note. But I can’t know for sure. Her work is present in de Jong's work, and I am grateful for it.

Frontlist: Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids edited by Cynthia Leitich Smith (middle grade short stories)

Sixteen Indigenous authors wrote the interconnected stories in this joyful middle grade anthology. The stories are about kids from many tribes and nations, but they’re all set at the Dance for Mother Earth Powwow in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

This book is overflowing with joy. Some of the characters are dealing with hard issues, including racism, alienation, poverty, and unstable homes. The authors don't erase or ignore these things. But the book doesn’t center suffering. What comes through loudest is Indigenous joy. Many of the stories are about dancing, food, language, ancestors, and the power of storytelling. It’s such an important reminder that books don’t have to be grim to be interesting.

So many of the stories capture the small but meaningful moments that define childhood. Christine Day’s “What We Know About Glaciers” is a beautiful story about sisterhood, in which a Coast Salish girl reconnects with her older sister at the powwow. In “Fancy Dancer” by Monique Gray Smith, a Cree boy gets dancing lessons for his first powwow from his stepdad. It’s all about the power of forming a bond with a loving adult.

There’s a ton of humor, too. In “Warriors of Forgiveness” by Tim Tingle, Luksi, a Choctaw boy, agrees to ride with a group of Choctaw elders on a bus from Oklahoma to the powwow. His Uncle Lenny has agreed to drive, but Luksi’s mom wants Luksi to make sure his uncle doesn’t get into any trouble. What follows is a hilarious and heartwarming road trip story. Rebecca Roanhorse’s delightfully playful story “Rez Dog Rules” is told from the perspective of a dog who accompanies his human friend to the powwow.

The collaborative nature of this book shines through in the vividness of the powwow. Everything comes to life: the vendors, the food, the dancers, the many families with their different reasons for being there. The various cultures, religions, and perspectives of the authors are reflected in the diversity of the characters. Collaboration as a theme is also shows up in the stories themselves. Some of my favorites are about kids from different tribes sharing their stories and learning from each other.

I also love how much untranslated Indigenous language appears in these stories. The glossary includes translations for words in Cree, Choctaw, Ojibwe, Cherokee, Tuscarora/Haudenosaunne, Navajo, and Abenaki, as well as some general information about Indigenous languages. I learned a lot from the glossary, and I also really value books that aren’t written with an outside audience in mind. Indigenous readers familiar with any of these languages will have a different experience of this book than I did.

I enjoyed this immensely, though I suspect an eleven-year-old might enjoy it even more. There’s sadness and loss, anger, mystery, friendship, humor, and a whole lot of joyful celebration.

Upcoming: Embodied: An Intersectional Comics Poetry Anthology edited by Wendy and Tyler Chin-Tanner (graphic poetry, A Wave Blue World, 5/18)

I don’t think of myself as reading a ton of poetry, though I do like to always have a collection going. But this is the third book of poetry I’ve recommended here! It’s also unlike any other poetry I’ve ever read. If you’re not a poetry reader generally, this book might be the one for you. It’s is a collection of twenty-three poems, illustrated by twenty-three different comic artists. What a wild and wonderful idea! The poems themselves cover a range of subjects, though many of them focus on gender, queerness, embodiment, race, and belonging. The contributors are all women and nonbinary folks.

I never would have thought to pair comics and poetry, but it make so much sense. They actually have a lot in common, and using them to inform each other creates something wholly new. As editor Wendy Chin-Tanner writes in the introduction:

While their tool kits might look different at first glance, both forms engage with distillation, the use of silence, the relationship between different parts of the page, and the interaction between visual content and negative space.

One thing I’ve learned about myself as a poetry reader is that I don’t like to linger over poems. I like to experience them in the moment and then let them go. Graphic poetry lends itself to this kind of reading, but it also slows me down. I read a few lines, looked at the art, read a few more lines, etc. There is so much to experience on every page. It invites a slow reading — not necessarily a careful reading, but a fully present one.

Image: An Instagram post from A Wave Blue World, showing an illustration from the poem ‘Birth’ by Wendy Chin-Tanner, drawn by Miss Lasko-Gross. It shows a pregnant Asian woman with a long black braid, holding a staff, standing on the side of a mountain.

Then there is the sheer brilliance of having artists illustrate poems. There’s so much openness in this. Illustrated, the poems become something new, the poet’s original vision translated into visual language. Each piece is a collaboration. The artist’s interpretation of the poem becomes a part of the poem itself.

Some of the artists interpret the poems as stories with beginnings, middles, and ends. Carola Borelli illustrates “Good Bones” by Maggie Smith literally: a realtor shows a young couple around an apartment. Others pieces are more abstract. In one of my favorites, “Rubble Girl” by Jenn Givhan, artist Sara Wooley draws each line as its own world. The images bring the words to life in dozens of surprising ways.

Image: An Instagram post by Sara Woolley, showing an illustration from the poem “Rubble Girl”. A brown-skinned woman with long dark hair sits in a pool of water. Her rib cage is open, drawn as a ribbon unraveling into the water. Several blue plants float on the surface of the pool.

There’s no way to translate the specific experience of reading this book into a review of it. Reading is always a kind of collaboration between the reader and the writer. This book is an exploration of that weird, complicated relationship. It blurs the lines between artist and writer, creator and interpreter, speaker and listener. It’s a beautiful merging of artistic visions — sometimes harmonious, sometimes contradictory. My very favorite poetry creates space: for new possibilities, new ways of seeing the world and understanding myself, new kinds of language. This book creates that space.

The Bake

This is a magical collaboration in so many ways! The recipe is from Sweet, written by Yotam Ottolenghi and Helen Goh. The brownies are a collaboration between tahini and chocolate, one of the best collaborations ever. I could eat tahini and chocolate forever in any combination, but this is one of my absolute favorites.

Tahini Halvah Brownies

Makes 16 big brownies

I use whole-grain spelt flour in these, because I love it, but the original recipes calls for AP, so feel free to use that. I also reduced the sugar, but if you like a bitter brownie, you could reduce it further to 235 grams. Finally, be sure to use a 9-inch square pan (or adjust the baking time). I used an 8-inch square and when I took the brownies out after 35 minutes, they were still gooey. This King Arthur article outlining common baking pan size substitutes is super helpful.

Ingredients

250 grams (9 1/2 Tbs) unsalted butter, cut into chunks

260 grams (9 ounces) bittersweet chocolate, roughly chopped (unless you’re using my favorite feves)

4 eggs

255 grams (about 1 1/4 cups) toasted sugar (untoasted sugar is fine, too)

120 grams (3/4 cup plus 3 Tbs) whole-grain spelt flour

30 grams (1/3 cup) cocoa powder

1/2 tsp salt

200 grams (7 ounces) halvah, broken into small pieces (my current favorite halvah is made by Al Kanater in Lebanon, but so far I’ve only been able to find it on Amazon, so I haven’t bought any in a while)

12 grams (1 Tbs) dark brown sugar

70 grams (1/3 cup) tahini

Preheat the oven to 400. Butter a 9-inch square baking pan and line it with parchment.

Melt the butter and chocolate in a heatproof bowl set over a pan of simmering water, stirring frequently. Set aside and let cool to room temperature.

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, or with handheld beaters, whisk the eggs and sugar until pale and thick, 3-4 minutes. Add the cooled chocolate and mix gently with a rubber spatula.

In a small bowl, combine the flour, salt, and cocoa powder. Gently fold the flour into the chocolate mixture. Add the halvah and continue to mix gently until everything is combined. Scrape the batter into the prepared pan and smooth out the top.

Mix the tahini with the brown sugar. Drizzle the tahini mixture over the top of the brownies, dolloping spoonfuls everywhere. Use a long skewer or butter knife to swirl the tahini, creating a marbled pattern. If you want, scatter sesame seeds (black, white, or a combo) on top. Bake for 23-25 minutes. The middle should have a slight wobble. The brownies will firm up as they cool. (Unless, like me, you’re impatient and take them out when you know you shouldn’t. Then you’ll have delicious gooey fudge.) They’ll keep for about five days, and they freeze beautifully.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Sweet Potatoes & A Can of Black Beans

Things are nuts in my life right now and I have not been cooking. I did mange to make this tasty goat cheese and asparagus pasta. Beyond that, I’ve been eating a lot of eggs and toast. Cooking up some beans and sweet potatoes the other night was a big win, so that’s what I have for you today. It’s not very inspiring, but it’s tasty!

Cut a large sweet potato into wedges; roast with olive oil, salt, pepper, and cumin for 20-30 minutes at 450. Meanwhile, open a can of black beans. If you’re feeling fancy (I wasn’t), sauté an onion and some garlic. Drain and add the beans. Season with the spices of your choice (mine: cumin, cayenne, oregano). Mash up the beans a bit if you like them refried. Pile the beans into a bowl, followed by the roasted sweet potatoes and some grated cheddar. Top with salsa, scallions, or cilantro (none of which I had).

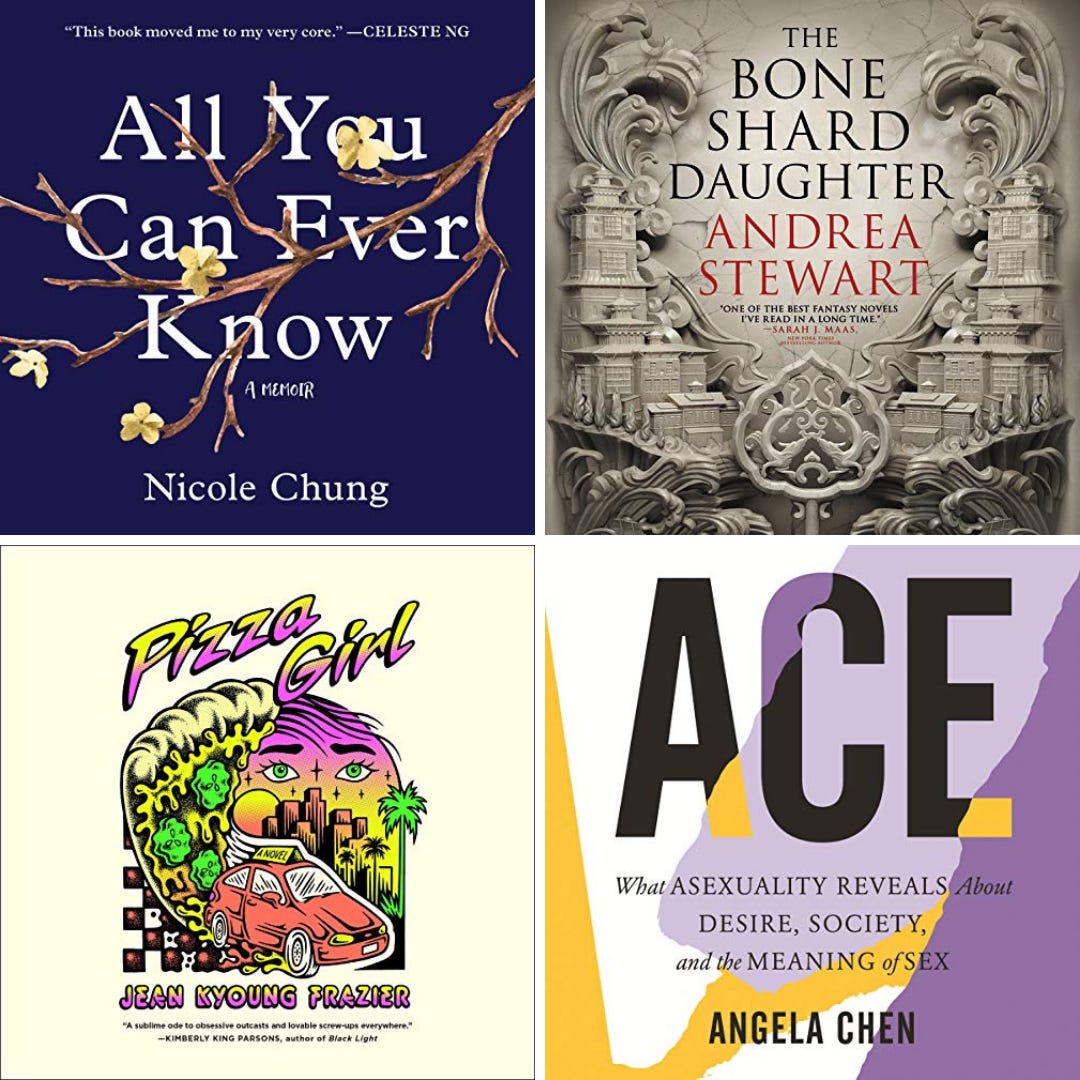

The Beat: Audiobooks by Asian American Authors, Read by Asian American Narrators

Once again, I’m listening to a book I’m planning on featuring here soon. So, since May is AAPI Heritage Month, I thought instead I’d share a few of my favorite audiobooks written and read by Asian American authors. These are just four out of many!

Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier, read by Leena Yi: A stunning novel about a pregnant teenager who becomes obsessed with an older woman, a customer at the pizza shop where she works.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals about Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen, read by Natalie Naudus: One of my favorite reads of 2020! I loved it so much I bought a hard copy (even though the audio is great).

The Bone Shard Daughter by Andrea Stewart, read by Natalie Naudus, Feodor Chin, and Emily Woo Zeller: A dark fantasy novel with fascinating magic, flawed characters, queer love, and intersecting storylines.

All You Can Ever Know by Nicole Chung, read by Janet Song: A beautiful memoir about transracial adoption and how complicated family can be.

The Bookshelf

The Library Shelf

I read a whole bunch of library books this weekend! And then…I picked up a bunch of new ones. I have no self-control.

The Visual

I keep my to-read shelf on Goodreads at 100 books. If I want to add a book, and there are already 100 books on it, something has to go. I wrote a whole piece describing this complicated process. It works for me, and it means that my to-read shelf is a dynamic list, one I’m continually revisiting. Here are the five most recent additions.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I rounded up some of my favorite books featuring queer parents. If you enjoyed my newsletter about queer parenting, check out this list for more recs!

Now Out

Hooray! Stone Fruit by Lee Lai is now out — go forth and get yourself a copy!

The Boost

I suspect you’ve heard about what’s happening in Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem. As a Jew, I take it as my responsibility to speak up about it. Israeli settlers evicting Palestinians from their homes is not new; it’s part of the ongoing violence and ethnic cleansing of the Israeli occupation. Mohammed El-Kurd is a Palestinian writer from Sheikh Jarrah. I’ve found his work illuminating and powerful, particularly this piece, and his recent Democracy Now interview. He’s also compiled a list of resources and action items.

And, of course, some beauty to send you on your way: These are the two things that keep my heart full on a daily basis — my pup Nessa, and wide open vistas. Whatever keeps your heart full, I hope you get some of it this week.

Catch you next Wednesday, bookish friends!