Hello, word-devouring and treat-munching humans! It’s supposed to be in the 70s here in Western Mass tomorrow and I’m trying not to be too grumpy about it. Luckily, I have books, cookies, and a magic salad to distract me from these not-appropriate-for-March temperatures.

This week’s theme arose because I’ve recently read a bunch of stellar anthologies and I want to talk about them. There is so much to love about an anthology! I’m a big fan of reading about a subject from many different perspectives, and an anthology is a great way to do that. I also love the way pieces in an anthology converse with each other. My favorite books are ones that build on themselves, and this happens all the time in good anthologies.

I came to all three of these books in different ways, and that’s another thing I love about anthologies. Sometimes I pick one up because I’m interested in the subject matter, and sometimes because I’ve enjoyed books by some of the contributors. Either way, an anthology is an opportunity: to enjoy new work by beloved authors, to discover new authors to fall in love with.

The Books

Backlist: Shapes of Native Nonfiction edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton (Essays, 2019)

This collection of essays by contemporary Indigenous writers exemplifies everything I love about anthologies. Reading each piece felt like stepping into a new world. I never knew exactly what I was about to discover. Though there are common themes that run throughout the collection—family, history, land, trauma, memory, the act of writing itself—no two essays are alike. There’s an incredible diversity of styles and subjects.

I especially appreciated the way Washuta and Warburton organized the book. Rather than arrange the essays by subject or theme, they’re sorted into four sections, based on the structures of the essays. This is purposeful. As they explain in the introduction, they’re just as interested in the vessel (i.e. the form of the essay itself) as they are in its content. From the introduction:

“The basket. The body. The canoe. The page…[N]one of these vessels can be defined solely by their contents; neither can their purpose be understood as strictly utilitarian. Rather, the craft involved in creating such a vessel—the care and knowledge it takes to create the structure and shape necessary to convey—is inseparable from the contents that vessel holds. To pay attention only to the contents would be to ignore the very relationships that such vessels sustain.

Yet it is often on these terms that Native literatures, particularly works of nonfiction, are discussed: as works whose import is related exclusively to their content.”

This anthology is a direct response to that limiting idea, and a beautiful, powerful one. It made me rethink the possibilities of the essay as a form of creative nonfiction. It rattled and upended my own preconceived ideas about what an essay should look like. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how our biases, conscious and unconscious, influence how we experience story, how we define storytelling. There were essays in this collection that moved me more than others, but every one of them spoke to this idea. How does my whiteness bleed into the way I read an essay, the way I expect or want it to begin or end? What worlds of story open up when I actively push back against the settler colonial literary framework that I’ve been taught, that lives in my body? That’s not a question I can answer yet, but wrestling with it is the kind of work I want to be doing as a reader.

There are too many wonderful essays in this book to write in detail about all of them. In “Letter to a Just-Starting-Out Indian Writer—and Maybe to Myself”, written as a list of advice, Stephen Graham Jones brilliantly explores the complexities of writing (and not writing) about identity. Deborah A. Miranda’s essay “Tuolumne”, about her father returning to the Tuolumne River after getting out of prison, flows from beginning to end like the river itself.

If I had to pick a favorite, it would likely be “The Way of Wounds” by Natanya Ann Pulley. The essay is split into several sections, each beginning with a list of words, which Pulley then explains, imagines, unearths, complicates. She weaves all of these seemingly disparate pieces into a startling work about pain, memory, family, and moving through the world in a constantly shifting body.

I got this from the library, but I’ll definitely be adding it to my to-buy list. Both as a writer and a human, it’s one I’m going to want to revisit.

Frontlist: Kink: Stories edited by R.O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell (Short fiction)

I read this book about a month ago. Before sitting down to write this review, I decided to see how many stories I could remember without opening the book. I was honestly shocked by how many it was:

Zeyn Joukhadar’s lush and beautiful story about a trans couple and their straight peeping-tom neighbor. I can still see this couple’s kitchen and feel the ease and care with which they share space.

Roxane Gay’s very short story about a woman and her wife, the sex they have, the faces they present to the world, the faces the present to each other, the faces they keep to themselves. I’m still wondering how she packed so much character into so few pages.

R.O. Kwon’s story about a couple who seeks help from a professional dominatrix. Kwon writes so poignantly about silence and desire.

Peter Mountford’s story about a couple visiting an old friend, wondering if (and how) to come out about their kinkiness.

Larissa Pham’s story about a young woman’s weekend getaway to Vermont with her older boyfriend, and the ways it changes their relationship.

The longest story in the book, Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror” (also the longest title). It has a strangeness similar to some of the stories in Her Party and Other Parties. For thirty-five of its fortyish pages, I wasn’t into it. It was disorienting and dreamlike and upsetting. I was already composing my review in my head: “too bad the longest story in the book was my least favorite!” And then, in the last few pages, everything changed. Machado worked some magic that left me breathless. I’m still thinking about it today.

Generally I have a lot of trouble remembering short stories after I read them. It’s not uncommon for me to read a collection and only remember one of the stories, at best. I stopped reading short story collections for a while because of this (and wrote about it). Something about all those stories squished together makes them run together in my mind, and I rarely end up loving a whole collection. But I absolutely loved this one, and the fact that so many of the stories are still so clear to me is proof.

All the stories in this book are about desire and intimacy and the strange terrain of longing. They’re mostly contemporary, but there are also some dystopian and historical ones. Two thirds of them are about queer and trans people. They explore many kinds of kink in many different contexts. There is definitely explicit sex in some (though not all) of them, so if that’s not your jam, maybe skip this one. But they’re not all about sex, and that’s something I really appreciated; kink isn’t always about sex, either.

When I was taking a lot of creative writing classes in my early twenties, one of the things teachers said over and over again was: you have to know what your character wants. And while I no longer think that all fiction needs to follow this rule, there’s no denying that desire is a driving force in our lives. Maybe that’s part of what makes these stories so propulsive. Every one of them is about desire. Sexual desire, yes, but also the desire to be seen and known, to be useful, to be cared for. The desire for power, autonomy, control, rest. Some of the stories are about a specific concrete desire, and others are about more complex desires, ones that are harder to see, that emerge over time. I truly think there’s a story in this book for everyone, because they’re all about the thorny work of trying to unravel what the hell we want and how to get it.

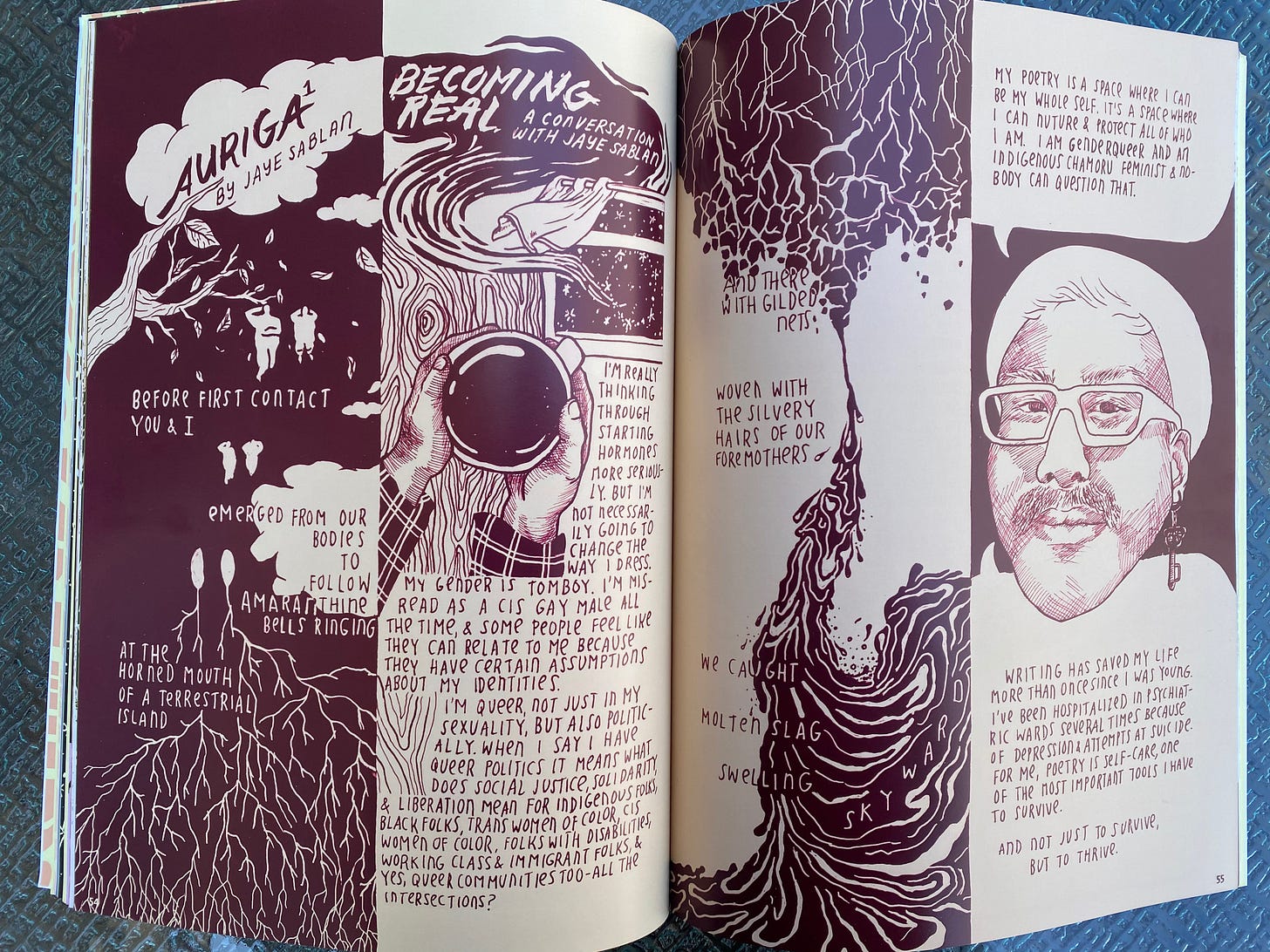

Upcoming: Our Work Is Everywhere by Syan Rose (Nonfiction, Arsenal Pulp Press, 4/6)

This book is beautiful and breathtaking, full of heart-healing and fist-pumping wisdom. I’m pretty sure any attempt I make to describe it is going to shortchange it. Here’s what Syan Rose says in the introduction:

“Our Work Is Everywhere is an anthology of illustrated interviews with & writings by queer & trans organizers, healers, artists, & comrades. It’s part graphic nonfiction, part thank-you note, part gay theory paper, part activist gossip column, & the rest is a surrealist dream in which we know why we’re here & what we need to do.

My goal is not to create one narrative about “the” queer or trans experience, but rather to create a textured, dynamic, & even paradoxical symphony of experiences that readers can relate to, learn from, disagree with, and be inspired by—to do and undo work, to envision & fine-tune dreams, to wonder ridiculous thoughts, to rest, to allow new selves to emerge…”

I love Rose’s expansive understanding of what work and social change can be. There are so many incredible pieces in this book, and I’d like to tell you about all of them. Here is just some of what you’ll find:

An interview with a group of fat, queer, femme performers who created “Fat: The Play”, a “performance piece that shares collective members’ experiences with body oppression, racism, classism & misogyny.”

A beautiful piece about the importance of trans elders and sisterhood by Vivi Veronica.

A conversation with Sze-Yang Ade-Lam and Anabel Khoo, two Asian martial artists and performers, about what martial arts have meant for them, personally and as part of radical justice work and community.

A bilingual piece about community-centered food justice in Washington, DC by Steph Niaupari.

A conversation about the power of queer astrology with Dusty Lamay.

There is so much richness in every one of these poems, interviews, conversations, and pieces of writing. This is a book to sit with for a long time. It’s celebratory and angry, reflective and challenging. It’s an invitation both to turn inward and to go loudly into the world.

I haven’t mentioned the art yet. Rose illustrates each piece, weaving the words into art, turning the pages of this book into a stunning visual journey. I often just looked at a page for several minutes before reading it. The intricate details, the different styles and colors, the interplay between words & art—all of it made me slow down and really look at (and listen to) what I was reading. Every now and then I pick up a book that changes how I think about graphic storytelling, and this is one of them.

As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes in her forward: “These stories are a queerly beautiful labor.” This piece of gorgeousness is out on April 6th, and you can pre-order it now.

The Bake

Look, I know everyone has their favorite chocolate chip cookie. I’m not trying to change any minds here. This one happens to be mine. Just like a good anthology, it’s got a little bit of everything. Also like a good anthology, everything in it fits together seamlessly.

This recipe is adapted (very slightly) from one of my all-time favorite baking cookbooks, Dorie’s Cookies. Anyone who knows me knows how I feel about cookies. I bake a few thousand every December. I have yet to find a cookie book better than this one. My copy is egg-stained and winkled, and even though I’ve been baking from it for years, I still haven’t tried every recipe. It’s an endless source of deliciousness and delight.

Multigrain Chocolate Chip Cookies

Makes 25 cookies

These cookies are crisp on the outside and soft in the middle. I honestly can’t tell you exactly what the combo of flours does, but it’s magic. Is it cliche to say that blending buckwheat and whole wheat flour adds a depth of flavor? Well, it does. Then there’s the crunch from the kasha and finely chopped pecans. I don’t like big chunks of anything but chocolate in my chocolate chip cookies, so I love the crunchy-but-not-chunky texture of of these.

I’ve made these cookies with many different flour combinations. Dorie’s original blend of AP, whole wheat, and buckwheat is still my favorite, but they’re also great with rye. This is definitely a cookie you can experiment with.

Fun aside: I didn’t know what kasha was until I made these cookies. It’s roasted buckwheat groats! I now have it in my pantry at all times, but I’ve never used it for anything other than these cookies.

Ingredients

68 grams (1/2 cup) all-purpose flour

68 grams (1/2 cup) whole wheat flour

60 grams (1/2 cup) buckwheat flour

1/2 tsp. baking powder

1/2 tsp. baking soda

7 Tbs. (99 grams) unsalted butter, at room temperature

134 grams (2/3 cup) brown sugar (I like dark brown, but either kind is fine! I also often reduce this to 120 grams)

100 gams (1/2 cup) sugar

1/4 tsp. salt

1 egg

1 egg yolk

60 grams (1/4 cup) kasha (Dorie recommends Wolff’s medium granulation and I concur, though I am by no means a kasha connoisseur)

60 grams (2/3 cup) pecans, toasted and finely chopped

7 ounces (196 grams) bittersweet chocolate, coarsely chopped

flaky salt for sprinkling

In a small bowl, whisk together the flours, baking powder, and baking soda.

In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, or using handheld beaters, beat together butter, both sugars, and salt on medium speed. Continue mixing for 3-5 minutes, scraping down the bowl as necessary. Add the egg, and then the egg yolk, beating between each addition.

Turn off the mixer and add the flour mixture all at once. Mix on low speed until most of the flour is combined (there should still be a few floury streaks). Add the kasha and pecans, and pulse a few times (you can also do this with a sturdy wooden spoon). Finally, add the chopped chocolate and pulse again, just until everything is blended.

Scrape the dough into a bowl and refrigerate for an hour. Longer is fine, too—the cookies just won't spread as much. You can also shape the dough into balls, freeze them, and bake them right from frozen.

Preheat the oven to 375. Using a tablespoon, scoop out mounds of dough. I like to roll them into balls between my palms. Place them on parchment-lined baking sheets about 2” apart. Sprinkle with flaky seat salt.

Bake for 9-12 minutes, rotating the sheets halfway through. The cookies will be just brown on the edges and still soft in the middle. Don’t worry if they seem underbaked—that’s how they should be! They’ll firm up a bit as they cool.

I have enjoyed these cookies for at least a week after baking, though they are absurdly good when still just a smidge warm.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: The Magic Salad

I am not a salad-for-dinner kind of person. I do love a good salad (you’ll be hearing from me during tomato season), but having one for dinner usually leaves me unsatisfied. So the fact that I’ve eaten this salad for lunch AND dinner at least once a week for the past month is really saying something. I don’t know why it’s so good. Honestly, it’s relatively ordinary. But there is something magical about this combination and I am hooked.

Dump some greens into a bowl. I like mixed greens, but use whatever you have. Grate a beet (I’m partial to golden, but any kind is fine) and a carrot. You can peel them if you want. Dump the grated roots into your bowl. Toast some pecans, break them up, and add those. Add some (golden) raisins. Crumble or cut up some blue cheese and add that. Make a dressing by combining olive oil (2ish Tbs), sherry or red wine vinegar (1ish Tbs), mustard (I dunno, maybe 2 teaspoons?), a pressed garlic clove, salt, and pepper. Pour it over your salad. Toss. Experience the magic.

You can obviously use this formula of greens + grated root + nut + dried fruit + cheese + dressing to make many other delicious salads.

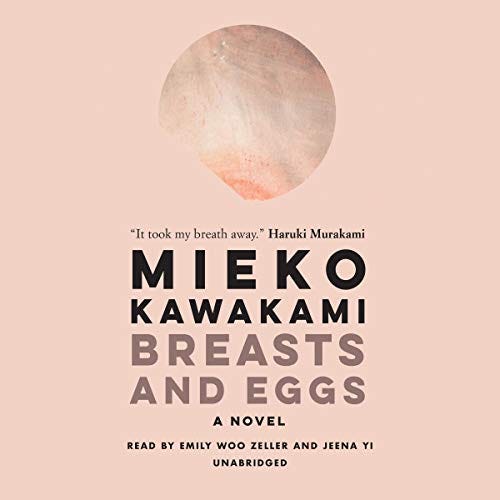

The Beat: Breasts & Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, translated by Sam Bett & David Boyd, narrated by Emily Woo Zeller and Jeena Yi

This is a relatively long audiobook (15 hours 21 minutes) and I’m about halfway through at the moment. I’m enjoying it. It’s split into two sections, both set in Tokyo. The first section takes place over the course of a weekend. The narrator, Natsuko, is hosting her older sister Makiko and her teenager daughter, Midoriko. Makiko is obsessed with getting breast implants. Midoriko won't speak to her mother or her aunt; she communicates by writing. The narrative is interspersed with her journal entires. The second section takes place ten years later. Natsuko, now in her late thirties, is not interested in sex, but she does want a child. She begins researching conceiving a child with a sperm donor.

So far my favorite parts of this novel have been Midoriko’s journal entries about her fears and insecurities surrounding her body, sex, and getting her period. This second half of the book that I’m in now meanders a lot. It’s a lot of Natsuko thinking and worrying and agonizing about having kids. I’m not saying this is bad! It’s just a particular kind of book: slow, full of ideas, and heavy on internal turmoil rather than external action. The audio is fantastic. Emily Woo Zeller is always good, and listening to it allows me to really sink into the Natsuko’s point of view.

I’m also finding Natsuko’s whole struggle (and exhaustion) with the expectations/assumptions around pregnancy and motherhood quite poignant. I’m a woman in my mid-thirties, and while I don’t have plans to have kids or get pregnant, it’s something I think about all the time. This book digs into the many, many opinions people have about women’s bodies—as well as parenting more generally—and the impacts those opinions have on people who have kids in nontraditional ways.

The Boost

First: It’s been a week since the murders in Georgia. I included a few resources for education and action in last week’s newsletter. Here are some more:

My fellow Book Rioter Patricia Elzie puts out a fantastic self-improvement newsletter, and last week she made a massive roundup of resources against anti-Asian violence. It includes education, action items, donations, book lists, additional resource lists, and mental health resources for the AAPI community. It’s very thoughtfully organized, and a great place to start if you’re feeling overwhelmed. Please check it out, and subscribe to her newsletter while you’re at it!

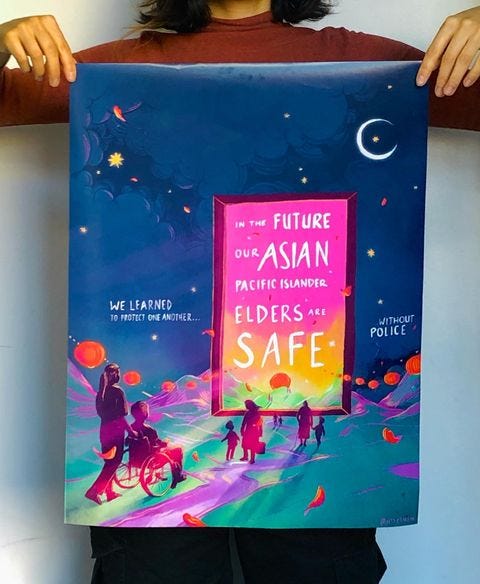

Artist Jess X. Snow made this beautiful print, which you can buy through Just Seeds as a set of four postcards or a poster. A portion of the proceeds will be split between Advancing Justice ATL, Red Canary Song, and Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence. I am an avid snail mail sender, so I was excited to buy a bunch of these postcards!

Image: An Instagram post by Jess X. Snow. A person’s hands and shoulders are visible, holding up an art print. It’s an image of several people, including kids, elders, and a wheelchair user, walking through a green expanse along a purple river toward a doorway-shaped portal. The portal has the words “In the future, our Asian Pacific Islander elders are safe” written across it. On a dark blue starry background are the words: “We learned to protect one another without police”. The colors are muted blues, greens, purples, pinks, and oranges.

Second: There are so many incredible activists, artists, performers, and healers featured in Our Work Is Everywhere. One of the things I love most about the book is how it acts an invitation. You will never hear me say that books aren’t powerful and important. But books do not create change. Change happens when you use your voice, your body, and your actions to make it happen. Author Lia Ko put it succently:

Image: An Instagram post by Ijeoma Oluo. A tweet from Lisa Ko appears against an orange background. It reads: “As a writer and reader of books, I am sorry to say that white supremacy is not going to be dismantled through diverse reading lists”

Our Work Is Everywhere is an example of how a book can be both a beautiful reading experience and a catalyst for change. So I wanted to highlight some of the people and organizations whose stories appear in its pages. Check out their work before you read the book (but definitely read the book!)

GLITS (Gays and Lesbians Living In a Transgender Society): Founded by Ceyenne Doroshow, an activist and organizer in the trans and sex worker communities, GLITS is a grassroots nonprofit that provides services and support for trans sex workers in NYC and beyond. You can learn more about their many projects and initiatives, donate, and find them on Instagram.

Thirdroot is a community healing collective in Brooklyn that offers yoga, acupuncture, massage, and other healing practices. I loved reading Rose’s conversation with Geleni Fontaine, one of the collective’s members, about ancestral healing, people’s medicine, and the deep connections between racial justice and health justice.

Phlegm is a Black artist from New Orleans whose work I am now obsessed with.

Trans Lifeline has a microgrant program that gives money directly to trans people. They offer 48 name change grants each month and also give microgants to trans people who are incarcerated. I loved reading about how this project got started and it’s exciting to see that it’s thriving.

Finally, a bit of beauty to send you on your way: This week my pup Nessa and I discovered a new conservation area near our house. It has several miles of trails, including one around this pond. I love all bodies of water, so this discovery has brought me a lot of joy in the past few days.

That’s it until next week. Happy eating, reading, and baking, everyone!

Just found this review of my book “Our Work is Everywhere”, thank you SO SO much for this. Your review really captured a lot of what I was intending with this anthology. This means a lot to me <3 Syan Rose