Volume 1, No. 19: Landscape as Character + Black Sesame & Lime Cake

Greetings, bookish humans! I’m back home after spending a week at the ocean with my family. It was the first time I’ve seen my nephews for more than a few hours in a year and a half. My oldest nephew made sugar-and-spice brioche buns and sticky buns! I also did a lot of this:

I already miss the ocean, but it is nice to be home (even with all the boxes), and I’ve got a regular newsletter for you this week. We’re talking landscapes in literature.

I am a place person. I often feel as strongly about the places I love as I do about the people I love. So I crave books with landscapes that are as central to the plot as any character. Reading books like this always feels like coming home. I relate so strongly to characters whose lives are intimately tied to the landscapes they inhabit.

These three books feature landscapes that act as essential characters. They’re all about the natural world (woods, the ocean, glaciers), but they’re also about human landscapes, and, most poignantly, the places where those landscapes blur and clash.

The Books

Backlist: Monkey Beach by Eden Robinson (Fiction, 2000)

This breathtaking novel is set in the 1980s in Kitamaat, a small village five hundred miles north of Vancouver, home to the Haisla people. Narrated in the first person by nineteen-year-old Lisa, the story begins when her brother goes missing while on a fishing trip. The present unfolds over only a few days; the bulk of the novel takes place in Lisa’s past, as she remembers her childhood and adolescence.

The northern landscape of Kitamaat is at the heart of the novel. So much of Lisa’s identity is caught up in the place she comes from. Robinson writes brilliantly about Lisa’s culture and the rhythms of life in a small village. But she also captures the shapes, textures, colors, and sounds of Kitamaat. There is so much ocean in this book; it’s inescapable. There are long descriptions of fishing for salmon and crabs, and of the process of making of oolichan grease, a concoction made from oolichans, a small fish from the smelt family. When Lisa goes blueberry picking with her grandmother, Ma-ma-oo explains to her the different kinds of blueberries and their different uses. Sometimes these passages take up many pages. Robinson’s descriptions of rural northern life are not romantic or cheerful. They’re real. Weather, wind, mountains, forest, ocean, and beach are always present, all the time.

The physical realties of living so close to the ocean are an integral part of Lisa’s Haisla identity. Her life swimming and fishing and foraging make her who she is. She loves her home, and she’s also trapped by it, bored by it, claustrophobic. So much of the landscape is reflected in Lisa herself. Like the landscape, which is both harsh and soft, dangerous and generous, she holds contradictions inside herself.

Lisa’s world is also full of unexplained happenings. There’s the little man who appears in her bedroom sometimes, often before a strange event. There’s b’gwus, the wild man of the woods, whom she glimpses every now and then, just for a moment. There are the ghosts of her beloved dead. None of this magical, however. It’s just a fact of Lisa’s life, one that I believed in absolutely.

I read this book back in January, and one thing (among many) that has stayed with me is the way Robinson chose to tell the story. It begins with Lisa and her family grieving over the presumed death of her brother. Lisa narrates a page or two in the present, and then slips into a memory, and the time shifts, and we’re in her childhood, often for dozens and dozens of pages. It’s so subtle that sometimes I didn’t even notice the shift until I’d resurface in the present. Lisa is exists in the present, but the past exists there, too.

This framework messes with my ideas about how a story with two timelines should unfold. I want a neat separation—different chapters, section breaks, empty space between the end of a scene in the present and the beginning of one in the past. But there is none of that here, and it makes the book both urgent and dreamlike, seamless and messy. Time may be linear, but memory isn’t. Neither is grief.

Sometimes when someone asks me what a book is about, I just want to shout “everything!” This book is like that. It’s about girlhood and grief. Family and ghosts. The way despair spirals. Fishing and cooking. Siblings and magic. Growing up and into something. There are a thousand threads running through it, which Robinson weaves into a complicated coming-of-age story about an Indigenous teenager living in a community that comforts her and traps her, knows her and refuses to see her, loves her and sometimes hurts her, holds her up and lets her go and calls her home.

Unfortunately, this book is hard to get in the US. I was able to get a copy from my library, but it’s not at Bookshop, and it’s a special order at my go-to indies. The link above takes you to Massy Books, a Canadian Indigenous-owned bookstore. I’ve had trouble getting Robinson’s other books in the US as well, which is frustrating, as I’m on a mission to read all of her work.

Frontlist: The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson (Historical/Contemporary Fiction)

In one of many beautiful scenes, Rosalie Iron Wing, the protagonist of this extraordinary debut novel, marvels at the power of a single seed:

Everywhere I looked, I saw how seeds were holding the world together. They planted forests, covered meadows with wildflowers, sprouted in the cracks of sidewalks, or lay dormant until the long-awaited moment came, signaled by fire or rain or warmth. They filled the produce aisle in grocery stories. Seeds breathed and spoke in a language all their own. Each one was a miniature time capsule, capturing years of stories in its tender flesh.

Like those seeds, cherished by generations of Dakhóta women, this novel holds years of stories within its pages. At once an intergenerational epic and a thoughtful character study, it unfolds through the distinct voices of four Dakhóta women, their lives braided together through history, family, shared grief, and generational wisdom. Their stories are deeply intertwined with the Minnesota landscape, which Wilson brings to life in all its complexity and nuance.

In the 1980s, after her father dies, Rosalie Iron Wing, like so many Native children, is placed in foster care. Cut off from her family, she marries a white farmer at eighteen, gives birth to a son, and spends the next twenty years tending her garden and struggling to teach her son the ways of her people in a mostly white and very racist town. When her husband dies in the early 2000s, she returns to her childhood home, determined to reconnect with the community she left behind. Slowly, with the help of the woods, the quiet of deep winter, and several Dakhóta elders, she begins to build her life anew.

Wilson skillfully weaves Rosalie’s personal journey with the parallel journeys of the women in her life: her great-great grandmother, her activist friend Gabby, and her great-aunt. Each of their lives fits differently into the sweeping histories at the heart of this novel: the forced removal of the Dakhóta people from their homeland in the 1860s, the rise of industrial farming and the polluting of the life-giving Minnesota River, and the unerring hope of ancestral corn.

It’s a book of contradictions, full of nuance. Wilson invokes so many different kinds of knowledge: the ancestral wisdom of plants, the gardening know-how of European immigrants, the science behind industrial agriculture, Indigenous foodways and seed-saving techniques. The interplay between these different ways of knowing and interacting with a landscape is the central conflict of Rosalie’s life. And it’s not a simple one.

Industrial agriculture is killing the land, but Wilson doesn’t demonize farmers. The book is about the legacy of colonization and the implications of white farmers owning and profiting off stolen land. Even though I sometimes wanted Rosalie to cut all ties to the farm where she lived for thirty years, she can’t force herself to do so. People don't live in a vacuum. The landscape exists as it is, with all its scars and history. It’s hurting, broken, life-giving and dying at the same time. So often, we think of natural and human landscapes in opposition to each other. It’s an unrealistic and simplistic way to see the world. Wilson, and Rosalie, refuse it. Rosalie’s life is tied to the land — emotionally, practically, financially, ancestrally. Seeds and stories and pollutants, the river and the farm, wild and cultivated plants — they’re all part of the complicated landscape that makes her who she is.

There are villains, including the Monsanto-like seed company. But there’s also a moving scene near the end of the book where Rosalie muses on how much she came to care for and respect her husband John. That’s what makes this book feels so real and alive. People are messy and layered and change their minds all the time. Rosalie and John don’t have a great marriage, but their marriage isn’t horrific, either. This same complexity exists in Rosalie’s relationship with her son Tommy. Rosalie hurts her son and is hurt by him. She hurts her father, and is hurt by him.

Near the end, when her aunt Darlene is telling Rosalie the story of their family, she says: “Your mother was not well. Whatever it was that had come home from the boarding school with your grandmother, it lived on in Agnes. She never found a way through it. It lives on until somebody finds a way to stop it.” This is such a heartbreaking moment, because it is so apparent that that violence, and the trauma it caused, lives on in Rosalie, and in Tommy. Wilson doesn’t tie everything up with a bow and a happy ending. The book ends with the possibility of healing. Rosalie begins to see how to stop that thing, even if she hasn’t done it yet.

Upcoming: Borealis by Aisha Sabatini Sloan (Nonfiction, Coffee House Press, 11/2)

If there’s one thing I love, it’s a book-length essay, and this is a new favorite. It’s also one of those books that I struggle to review, because Sloan’s prose is so sparse and exact. It’s hard to distill. I read it in one big gulp because once I got into it, I didn’t want to stop. It reads almost like poetry in some places — short paragraphs, beautiful language, quick and surprising movement between seemingly unrelated concepts.

Sloan is a biracial Black queer woman who has spent many summers living in Homer, Alaska. In this work, she explores herself and the Alaskan landscape. She writes about art and glaciers and the wildlife she encounters daily, about ex-lovers and encounters with strangers. She writes about being a Black woman in a place with so few Black people, and how that changes her experience of the landscape — and the landscape itself.

Something is swimming. I almost wrote, “I am the most interesting thing on this beach.” This is not how I talk, but when there is no Black figure, what am I supposed to like looking at? I think it’s a sea lion.

She’s constantly interrogating and redefining what it means to love the natural world and write about it. Her tone is sharp, sometimes absolute, always searching. She asks a question and answers it with another one. “I think my kind of pastoral must include gossip,” she writes at one point. Of the Black people in Homer, she says: “We are at about bald eagle to seagull proportion to the Whites here.” Later, this description: “The fog has lowered itself like haunches over a toilet across the tops of the mountains.” I can’t stop thinking about the brilliance of these lines. Nature is messy, often crass, and Sloan never lets you forget it.

Nature writing has historically been very white and male, and Sloan doesn’t let you forget that, either. She’s wary of the whole project: “Is nature writing just biding time until you’re hungry enough to eat?” she wonders.

I want to want a more intimate experience with nature but keep not turning down thinner trails, even ones that lead toward a potent memory, for fear of moose trampling or men.

There’s so much truth and so much reckoning in this passage. Sloan refuses to cater to white ideals of nature and what it means. She writes about the landscape as it is — awe-inspiring, wild, human-made, violent, bizarre. Notions of “purity” are so often tied up in wilderness, and purity is an idea that upholds whiteness. Sloan is writing against all of that. Nature isn’t pure. Wilderness does not exist apart from humans, immune to the forces of racism and patriarchy. She writes herself into the landscape — her Blackness, her queerness, her womanhood — but she does so matter-of-factly. She is the most interesting thing at the beach.

This is the nature writing at its best, playful and real, cutting and thoughtful, grounded in the physical and the emotional. Take this paragraph, full of so many layers of meaning and beauty:

After Anne Carson, I’ve written a “short talk on glaciers”: exhale colored mountain as the trajectory of an idea cracking. Natural hair is an idea of worth mined for resale. Hair as a way to visualize ideas, running rampant, old as time, unnoticed. Trampled, ivy, melting, bear-trodden, tree splintered, moaning, silent, aloud.

It’s out 11/2, and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

Last week I mentioned a few of my summer baking goals, including making this cake from Chetna Makan’s The Cardamom Trail. Well, I baked it! I’m happy to report that it is as delicious as I assumed it would be. Filling it with the most luscious lime curd I’ve ever had the pleasure to eat was not a bad idea, either.

Black Sesame & Lime Cake

Makes one 8” cake

The original recipe makes a loaf cake. I tweaked it a bit and turned it into this luxurious sandwich cake. If you don’t feel like making the curd, you can bake this in a round pan or a loaf pan. It’ll still be zesty and delicious and a tiny bit savory, thanks to the sesame. But it’s worth making the curd. It is truly amazing.

Ingredients:

For the cake:

3 Tbs sesame seeds (black, white, or a mix)

150 (1 1/4 cups) grams all-purpose flour

2 1/2 tsp baking powder

1/2 tsp salt

150 grams (10 1/2 Tbs) unsalted butter, at room temperature

150 grams (3/4 cup) white sugar

Zest of 2 oranges

1 Tbs orange juice

3 eggs

To finish:

One recipe lime curd: This is my absolute favorite curd recipe. I can’t overstate how smooth and delicious it is. Just use limes instead of lemons. Depending on how thick you want your curd layer to be, you might have extra. That’s okay! I assume you know what to do with a spoon.

Zest and juice of 1 lime

A few scoops powdered sugar (sorry, I know this is inexact)

Sesame seeds, to decorate

Butter an 8” round cake pan, line it with parchment paper, and set aside. Preheat the oven to 350.

In a small skillet, toast the sesame seeds until they’re fragrant and just starting to brown, about 3 minutes. Crush them lightly in a mortar and pestle, or with the the back of a wooden spoon.

In a small bowl, mix together the flour, baking powder, and salt.

In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, or with handheld beaters, cream the butter and sugar until light and fluffy, about 3 minutes. Add the orange zest, juice, and eggs. Beat on low speed to combine. Add the flour mixture and mix until just combined. Mix in the crushed sesame seeds on low speed.

Scrape the batter into the prepared pan. Bake for about 35 minutes, until a tester inserted in the middle comes out clean. Let cool completely, and then turn out the cake and split it in half.

While the cake is baking, make the curd. Let it rest in the fridge for an hour or so before spreading.

Once the curd is set, place the bottom half of the cake on a plate. Spread the curd in an even layer, and top with the other half of the cake. Make a quick glaze by sifting a few scoops of powered sugar into a bowl and slowly adding the lime juice until you reach a consistency you like. Drizzle over the cake. Sprinkle the lime zest and sesame seeds on top. The unfilled cake will keep for a few days on the counter; the filled cake keeps for a week or so in the fridge.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: 4 Ingredient Tomato Sauce

Tomatoes have started popping up at farms around the Valley. When I was a farmer I rarely ate tomatoes until we were swimming in them in August. These days, I can’t resist the early ones, and all the easy meals they bring. This is my absolute favorite tomato sauce: simple and comforting. If you count the olive oil, salt, and pepper, it has seven ingredients, but who’s counting?

Thinly slice two large onions. Sauté them in a generous pat of butter, olive oil, or a combination. Once they’re soft and starting to brown, add a head of garlic, pressed. Yes, I use a whole head. Continue cooking over low heat until the onions are close to caramelized, about twenty minutes. Add 3-4 pounds of diced sauce tomatoes, a pinch of salt, and some pepper. Continue cooking over medium heat, stirring frequently, until the sauce thickens. Remove from the heat and add a big handful of chopped basil. Serve over pasta with lots of Parmesan.

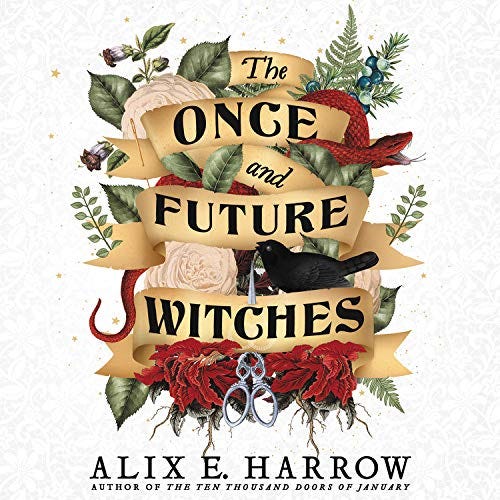

The Beat: The Once and Future Witches by Alix E. Harrow, read by Gabra Zackman

People have been telling me to read this book forever. Or at least since ARCs became available sometime last summer. So, a year. Anyway, I’m reading it now and I’m enjoying it. It’s set in New Salem in the late 1800s. The world used to be populated by powerful witches, but they were persecuted and driven into hiding. The story follows three sisters trying to bring witchcraft back, each with her own motivations and desires.

Like The Ten Thousand Doors of January, this feels like a book I can just luxuriate in. I’m not quite as attached to the characters as I thought I might be (that whole not being in the mood for fantasy in 2021 thing), but it honestly doesn’t even matter. I love the commentary on power and magic and women. I love the way spellcasting works. I love the world-building. I love the prose. Gabra Zackman’s narration is excellent, too.

The Bookshelf

The Visual

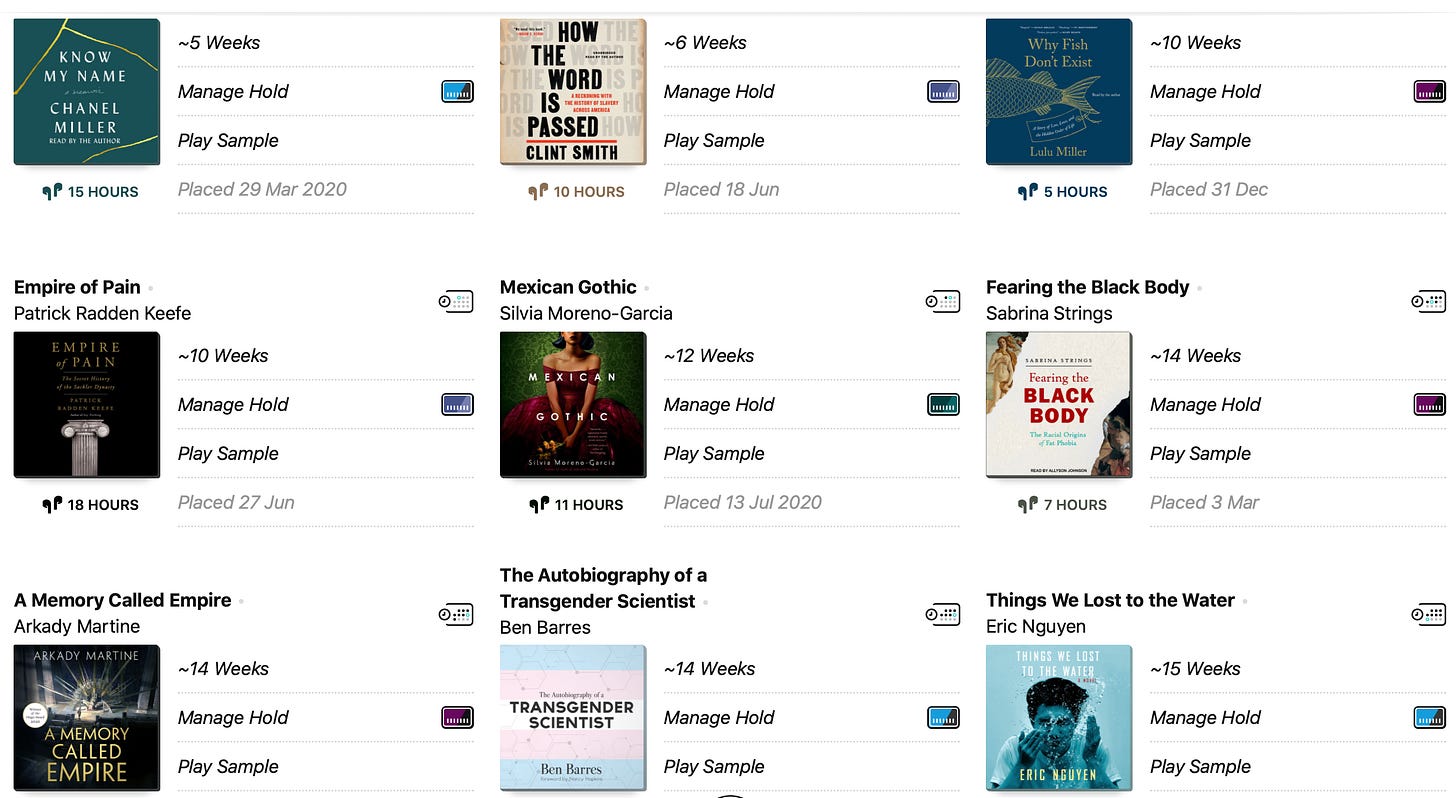

I currently have 30 audiobook holds on Libby. Is that a lot? I don’t know anymore, I can’t stop myself! My long holds list used to stress me out, but now I can just delay delivery of books I’m not ready to listen to. It’s my favorite feature on Libby. Anyway, here are nine of the thirty.

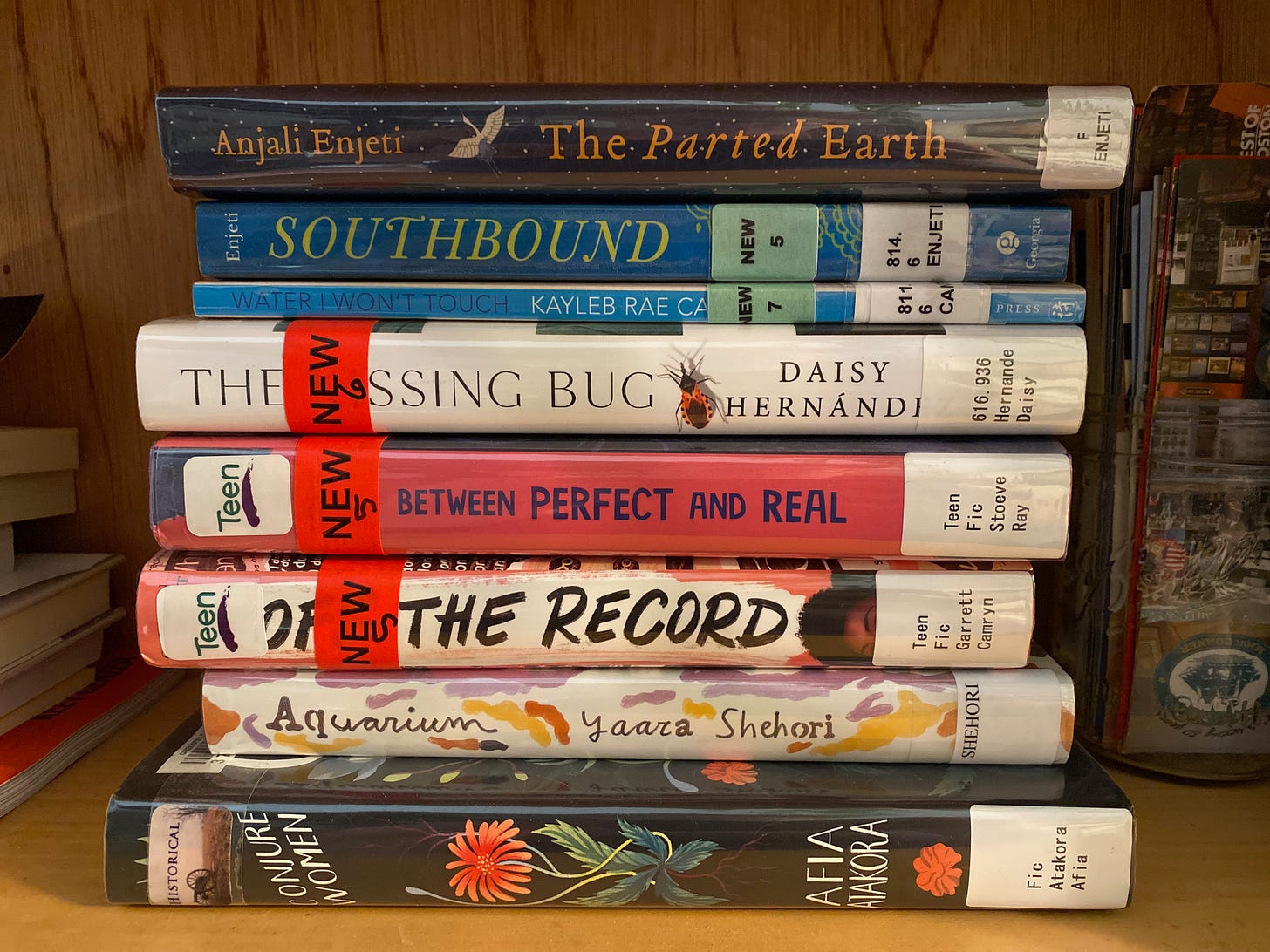

The Library Shelf

I’m in the process of (slowly) painting my house, which means unpacking is also happening slowly. Here’s my temporary shelf of library books. My reading has dipped a lot in July, so who knows how many of these I’ll get to. I did just start Water I Won’t Touch by Kayleb Rae Candrilli, which I’m loving.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I wrote a love letter Metonymy Press, and I rounded up some comics and graphic memoirs that embody queer joy. I also have a new monthly column at Audiofile, Triple Play. The first one features three audiobooks on being a woman artist.

Out Now

Hooray! Home of the Floating Lily by Silmy Abdullah is now out. Go forth and find yourself a copy.

The Boost

This week’s books are all about the importance of landscapes, and how we as humans relate to the land. Two of them are by Indigenous authors and deal directly with the legacies of land theft and colonization. So I wanted to share a few resources about land acknowledgement and voluntary land taxes that I’ve found useful.

Native Land has a useful guide about how and why to make land acknowledgments, including resources for further actions in solidarity with Indigenous peoples.

The Native Governance Center also has a comprehensive guide to land acknowledgment. It breaks down why land acknowledgements are important, and why an acknowledgement alone is not enough.

Voluntary land taxes are one way that non-Indigenous people can acknowledge that we’re living on and benefiting from stolen land. This article explains what voluntary land taxes are and includes some examples of existing land taxes, as well as steps for what to do if one doesn’t already exist in your area. It’s part of a “Beyond Land Acknowledgment” series of articles from the Native Governance Center.

Resource Generation also has a collection of resources on voluntary land taxes, reparations, and land acknowledgment.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I spent last week in my favorite place on earth. The ocean is my first and forever love.

And that’s it until next week! Catch you then.