Greetings, word-lovers and treat people, and welcome to all of you who found your way here via my piece about how to read less last week. I’m thrilled to have you.

On Friday I went into a bookstore for the first time in fifteen months. It was also the first time I’d been to my new local indie, Broadside Books, since I moved a year ago.

It was lovely. I spent an hour browsing and bought myself some books. I also thought about how much we’ve lost over the past year, and how fragile it all still feels. I suspect reentry is going to be a strange process for many of us. I hope we can use it as an invasion to be gentle with ourselves and each other.

This week’s books are all about something that has slowly taken over my reading life (and my brain) this year: translation. I’m fascinated by what translation can teach us about the world. How do we translate truthfully, not just between languages, but between kinds of language? What does translation mean in relation to experience?

So much of the world screams at us that there is only one right way: one way to move (on two biological legs), one way to speak (with words, out loud), one way grow up (get married, become a productive worker), one way to be sick (get better). Of course these are all lies that exist to uphold patriarchy, ableism, white supremacy.

Translation is the opposite of that one-right-way mentality. The act of translating is essentially the act of creating a different way. I’ve recently started listening to graphic novels on audio. It’s one of my favorite things. A graphic novel translated into an audiobook creates space: where before there was only one kind of story, now there are two. One is not better than the other. They are simply different. This is what I love about translation. It encourages openness and creativity. It builds doorways. There are so many ways to experience a book, a song, a river. Translation celebrates all of them.

I want a world that’s radically inclusive, that honors infinite ways of being. Translation, I think, is one of the things that brings us closer to that world. It’s not a perfect tool (it can certainly be used as a form of violence), but it’s a powerful one.

The Books

Backlist: The Bees by Laline Paull (Fiction, 2014)

There are so many non-human entities in the world: creatures, trees, wind, ocean currents, rock. I’m not sure it’s possible to translate the experiences of any of these entities — whether they’re sentient or not — into human ways of being. I do think attempting that translation holds a lot of possibilities. What can we learn when we imagine what a translation from a rock’s perspective, or the language of ants, might look like? The Bees is an attempt at that kind of translation.

The story is about Flora 717, one of thousands of sanitation worker bees tasked with cleaning up all the waste her hive generates. But Flora isn’t a typical bee — she’s not quite content to “accept, obey, and serve” as the hive mind directs her. Her curiosity, stubbornness, and ingenuity get her into all sorts of scrapes and adventures.

Stories about talking animals are nothing new. This one feels different from some others I’ve read, because Paull doesn’t attempt to make her bees act like humans. Of course they still do, to a certain extent. She’s writing from a human perspective, one she can’t escape. But the novel feels so authentic that I have trouble placing it inside a genre. I wouldn’t classify it as fantasy or science fiction, although technically it is. There’s no magic. The future setting is irrlevant. It’s just a story about bees.

Paull clearly based her made-up bee social structure on what we actually know about bees. But science is only a jumping-off point for a fascinating imagined bee culture, with its own mythology, history, and government. There’s not a ton of plot in this book; the joy of it comes from each new revelation about the hive. As Flora goes about her work, we glimpse its strange and complicated machinery in action: the cult-like religion, the foragers in the dance hall, the useless drones who sit around all day whining for workers to groom them.

Paull’s writing is gorgeous, particularly the way she writes about scent. I read this book a few years ago, and the overwhelming presence of scent in the prose is what I rememberer most vividly. Paull not only describes a stunning array of smells, but also the many ways bees use scent to talk to each other. Reading it, I felt completely immersed in a different kind of communication, even though I was reading a novel in English. There are visual descriptions, but they’re almost always accompanied by descriptions of smell, and often touch. I love this de-centering of the kinds of communication that we’re trained to value the most.

Humans do factor into the plot, but only as a danger to be avoided. The ways humans have changed (and often broken) the world are important to the story, and Paull delves into many themes that have relevance to human lives. The Bees is about systems of government (both oppressive and democratic), religion, how and why we communicate, purpose, the meaning of kin. Perhaps that’s what I love most about it: it’s a non-human story and a human one. It’s full of so many layers of translation.

Frontlist: The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus (Poetry)

Raymond Antrobus is a deaf Jamaican British poet. I was just looking at his website, and underneath his name it says: poet / writer / educator / investigator of missing sounds. In so many ways, this collection feels like an ode to missing sounds. Or maybe more truthfully, an ode to sounds ignored, unheard, untranslated.

These poems are are about so much: d/Deaf identity, biracial identity, Blackness, ableism, fatherhood, friendship, London, loss (specifically losing a father), language, ghosts. Throughout, Antrobus interrogates the uses of translation, both painful and creative: translation between verbal and nonverbal languages, between ways of speaking, between cultures and countries, between the different identities a person holds throughout a life.

In ‘I Move Through London Like a Hotep”, a poem about lip reading, he writes:

She said either do you want a pancake? or you look melancholic. The less I hear the bigger the swamp, so I smile and nod and my head becomes a faint fog horn, a lost river. Why wasn’t I asking her to microphone? When you tell someone you read lips you become a mysterious captain.

There is so much playfulness in the way he expands the spaces between what he hears and what he doesn’t. He takes misunderstandings and turns them into openings. But there’s also so much pain in these words. It’s not a funny joke, a laugh-it-off encounter. These two threads, the joy and violence that are both present in translation, run side by side throughout the whole book.

In “Dear Hearing World” he addresses the harm done to him, and to so many Deaf children, by the hearing: “I was a broken speaker, you were never a broken interpreter”. But this poem is also a celebration of Deaf worlds, and language the hearing can’t access.

The poem “Conversation with the Art Teacher (A Translation Attempt)” recounts a conversation between two people who don’t speak the same language. Here’s how it ends:

Wait, you write down what I say, how? You know BSL has no English grammar structure? How you write me when I am visual? Me, into fashion, expression in colour. How will someone reading this see my feeling?

This poem gets at the central question these poems seem to be asking: is translation even possible? How do we see each other across different ways of hearing, speaking, seeing, being? Antrobus doesn’t offer any answers, but the question itself is a powerful starting point.

Some of the poems are autobiographical and others create a chorus of other d/Deaf voices. Deaf ghosts and ancestors come alive. It makes the poems feel both intimate and expansive. There’s one particularly powerful series of poems based on interviews with a Deaf Jamaican woman living in the UK. They are beautiful and haunting and left me pondering the idea that storytelling is another kind of translation.

Upcoming: There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness by M. Leona Godin (Nonfiction, Pantheon, 6/1)

I love a book that blends memoir with criticism, history, and social commentary, and this is one of the most satisfying books of that sort I’ve read in a long time. Godin lost her vision gradually, over many years, and her experiences as both visually impaired and blind are interwoven with a far-ranging exploration of blindness itself. “Blindness is not just a subject; it is a perspective,” she writes in the introduction. Likewise, this book is both. It’s a deep dive into the history of blindness in literature, science, art, technology, philosophy, religion, and culture. That history is informed by Godin’s singular experience of blindness, her particular perspective. She goes on to say:

Blindness seems to have nearly irresistible appeal as a literary trope, but as such, it has lost the particularity and multiplicity of lived experience. Generally speaking, “the blind” are either idealized in theory, as being exceptionally pure or superpowered, or pitied in practice, as being inept or unaware. I think this is because blind people are rarely allowed to be the authors of their own image.

In this book, Godin not only authors her own image, but reframes the conversation. Blindness and sight, both literal and metaphorical, have long been understood as a binary, in opposition to each other. It’s an idea so deeply rooted in Western culture that as soon as you start thinking about it, you see it everywhere. Literal sight is equated with metaphorical blindness, while literal blindness denotes wisdom. Godin analyzes this idea in Homer and Milton, King Lear and Star Wars, Oedipus Rex and the Bible. But she doesn’t stop there. She refutes the blind-sight dichotomy altogether. Instead, she posits that blindness and sight exist on a spectrum, that the lines between the sighted and the blind are permeable:

If we understand seeing and not-seeing for what they are — a vast interplay of physical, mental, metaphorical, and social situations — then our various ways of experiencing the world will be expanded and refined for all of us, the sighted and the blind alike.

I do want to note that Godin is entirely focused on Western history, which she clearly states up font, so I can’t fault her for it, though I would have loved to read more about blindness in non-Western cultures. As it is, there’s so much fascinating material here. She writes about the invention of telescopes and microscopes, and how they changed the way we understand sight. There’s a chapter on the history of canes and other assistive technology blind people use to navigate, and how these tools are portrayed in the media and/or perceived by the sighted. She digs into the pieces of Helen Keller’s life that are not widely known, and then interrogates the simplified, reductionist version of her life that is widely known. She gets into the neuroscience of how sight functions in the brain. There’s a whole section on Louis Braille. I was riveted.

Her writing is vivid; detailed, but never dense. She’s just as interested in the lives of blind people today, in blind culture and art, as she is in Paradise Lost. She’s constantly making connections between the present and the past, which makes this a book for everyone.

She also writes frequently about translation — as an idea, an act, a philosophy, a necessity. In a chapter about art and accessibility, she interviews Andy Slater, a blind sound artist whose album Unseen Reheard includes written descriptions of each piece. Musing on these translations, Godin writes:

As with all translations, there will always be something lost and something gained. Embracing the challenge of verbal description for audio beautifully illustrates how translation from one sense to another can push art into new realms.

This book pushed me into new realms. Godin states that, with this work, she wanted to “open up a space for social justice that accepts sensorial difference, to celebrate the vast, dappled regions between seeing and not-seeing, blindness and sight, darkness and light.” As far as I’m concerned, she’s done just that. It’s out June 1, and you can preorder it here.

Godin is also the founder of Aromatica Poetica, an online journal that celebrates taste and smell — senses that often get neglected. I throughly enjoyed reading through it.

The Bake

It was so hot over the weekend here in Western Mass, and I can’t express how much I hate it. In rebellion, I decided to make a wintery cake yesterday instead of a springy one. I was always planning on making something with rhubarb for this week’s newsletter, since a) it’s rhubarb season and b) rhubarb is a fruit that requires translation. (Yup, this is how my brain works.) I’m sure there’s someone out there who likes raw rhubarb, but its real magic comes with transformation. Anyway, this is a delicious cake. Tart rhubarb goes so well with warm spices like ginger and nutmeg.

Spiced Rhubarb Upside-Down Cake

Adapted from Smitten Kitchen

Makes one 10” cake

Ingredients:

For the topping:

1 pound (450 grams) trimmed rhubarb

150 grams (3/4 cup) white sugar (if you’re new here, may I kindly introduce you to my obsession, toasted sugar?)

Grated zest from half a lemon

4 Tbs (55 grams) unsalted butter

Pinch of salt

For the cake:

6 Tbs (85 grams) unsalted butter, softened

125 grams (2/3 cup) dark brown sugar (light brown is fine, too)

50 grams (1/4 cup) white sugar

2 eggs

1/2 tsp vanilla

2 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp salt

1 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp ground ginger

1/8 tsp ground cloves

1/4 tsp grated nutmeg (I always add more nutmeg than recipes call for; Deb says “a few gratings”)

1/3 cup (120 ml) buttermilk

195 grams (1 1/2 cups) all-purpose flour (I actually used 100 grams whole wheat pastry flour and 95 grams AP flour)

Preheat oven to 350.

Make the topping: Cut your rhubarb into lengths that will fit across the bottom of a 10” ovenproof skillet, all facing in the same direction. (I used my 9” cast iron, and it was fine.) Some will be shorter, some longer. You can use the actual pan as your guide. Cut the stalks lengthwise into thin strips, about 1/4” thick. If you’re working with thin stalks, you can simply cut them in half lengthwise.

Sprinkle the sugar into the bottom of the pan. Add the lemon zest and mix with your fingers. Add the butter and salt and cook over medium heat until the butter is melted, stirring frequently. Add rhubarb and cook for 3-5 minutes, turning frequently, until it has softened and released some liquid. Remove from heat and set aside.

Make the cake: In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a paddle attachment, or in a bowl with electric beaters, cream butter and both sugars until light and fluffy. Add eggs one at a time, beating after each addition, followed by vanilla. Add baking powder, salt, and spices, and beat to combine. Add buttermilk and mix briefly. Scrape down the bowl and add flour, mixing just until it disappears into the batter.

Dollop the batter over the rhubarb mixture and smooth the top as much as you can. Don’t worry about getting it totally smooth or making sure all the rhubarb is covered; it’ll work itself out in the oven.

Bake for 35 minutes, until a tester inserted into the cake (not the topping below!) comes out clean. Transfer to a rack and let cool for 5 minutes before running a knife around the edges. Put a large plate upside-down over the skillet and use potholders to flip the cake onto it. It’s delicious warm, and I imagine a dollop of ice cream or whipped cream would be lovely. It’ll keep for a few days at room temp or a week in the fridge.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Cumin Lamb with Bok Choy

I made this a few weeks ago and I’ve been dreaming about it ever since. It’s one of those dishes that I never considered making at home, and then I did, and it’s so good, and so simple. It will be featuring prominently in my cooking rotation from now on.

Toast cumin seeds (1 Tbs), Sichuan peppercorns (2-3 tsp), mustard seeds (1-2 tsp) and coriander seeds (1 tsp) in a dry skillet until fragrant. Crush them in whatever way you crush spices. I smashed mine against the side of a bowl with a glass jar for a while. Thinly slice the meat and toss it in a bowl with the spices, some salt, and whatever kind of heat you like (dried chiles, crushed red pepper, etc). Thinly slice an onion. Wash and thinly slice a few heads of baby boy choy (or one big one), keeping the white and green parts separate. Press three garlic cloves and set aside.

Heat a large skillet or wok over high heat until very hot, 3-5 minutes. Add 2 Tbs peanut oil. Toss in the onion and white parts of the bok choy. Cook until lightly browned but still crisp, about 2 minutes. Transfer to a bowl. Add the spiced lamb to the hot skillet, tossing as the meat browns. Add garlic, bok choy leaves, and 1.5 Tbs each soy sauce and Chinese cooking sherry (I used rice wine because that’s what I had.) Cook until most of the liquid has evaporated and the meat is tender. Toss in the onions. Serve over rice, garnished with cilantro and scallions.

The Beat: Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse, read by Cara Gee, Nicole Lewis, Kaipo Schwab, and Shaun Taylor-Corbett

I’ve been meaning to read this since it came out last fall. So many book people I know have been raving about it! And I can see why. Roanhorse has created a world that feels effortlessly real, full of history, culture, religion, mythology, and magic. It’s all so easy to imagine: the ocean, the cities, the food. That said, I’m not head-over-heels for it. I think this is mostly me — I haven’t been in a fantasy mood all year.

There’s also a blind character in this who has a particular spiritual destiny, marked by his blindness. I’ve been thinking more deeply and critically about the blind prophet trope since reading There Plant Eyes. Being neither blind nor Indigenous (this novel is inspired/influenced by Indigenous cultures of the Americas), I don’t think I’m qualified to completely untangle all the threads of how that trope plays out here. But I’m certainly tugging on them as I read.

In other audiobook news, I just finished The Groom Will Keep His Name by Matt Ortile, which I loved.

The Bookshelf

The Library Shelf

I always get super excited about reading in January and request about a hundred books from the library during the first few months of the year. This is the smallest number of library books I’ve had checked out in ages! I’m trying to refocus on books I own for the second half of 2021. We’ll see how it goes.

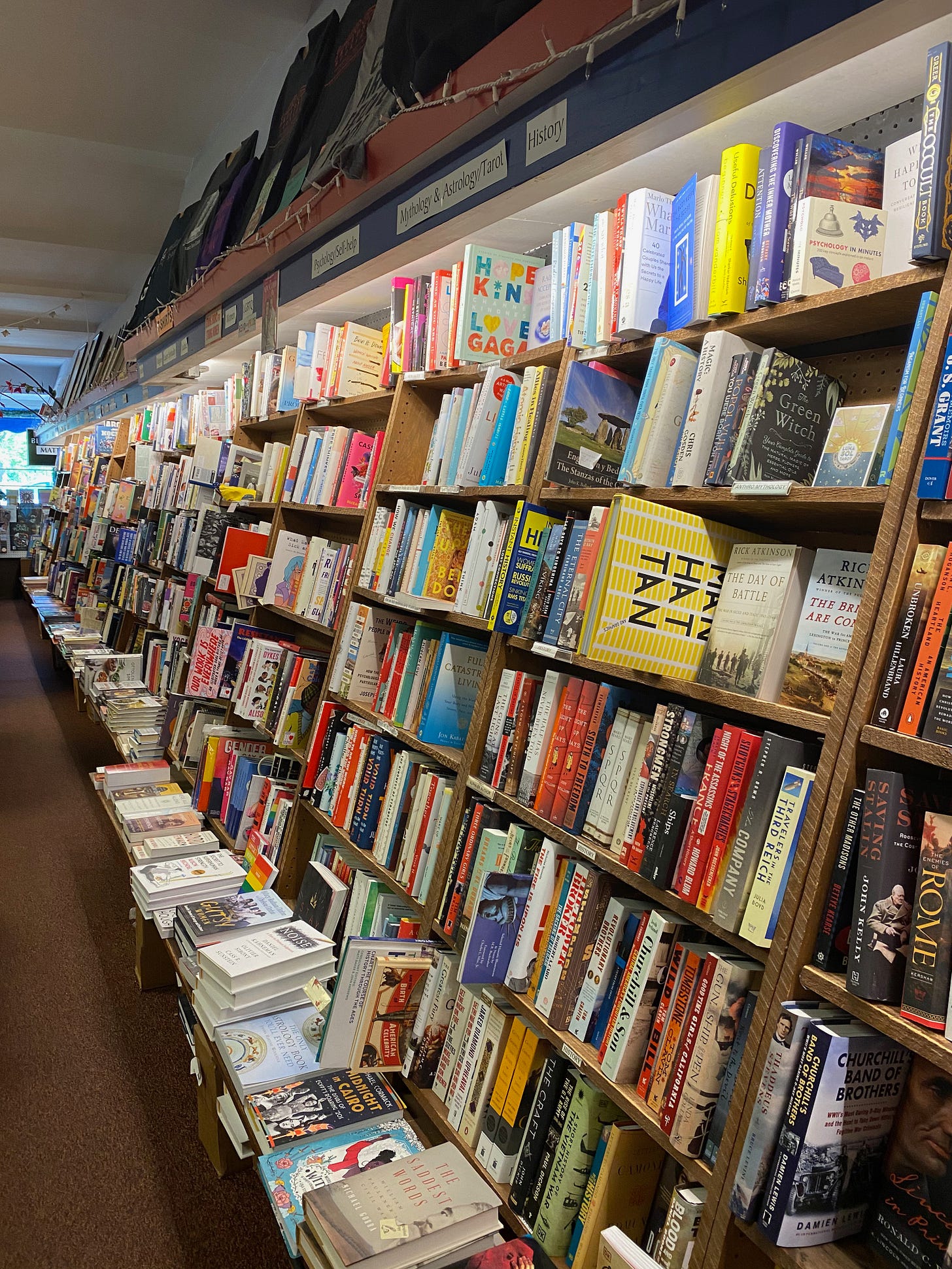

The Visual

Earlier I mentioned going to a bookstore for the first time in over a year. I bought books! Here they are:

Now Out

Hooray! Embodied: An Intersectional Feminist Comics Poetry Anthology edited by Wendy and Tyler Chin-Tanner, is now out. Go forth and find yourself a copy!

Around the Internet

I wasn’t kidding earlier when I said I wrote a piece about how to read less.

Two book reviews (not written by me): one about a book I loved, and one about a book I now want to read.

The Boost

Because we’re talking about the possibilities (and necessity) of translation, I wanted to share some resources about adding image descriptions to online content. Access is about creating a world in which all people, disabled and nondisabled, can thrive in all spaces: physical and digital, inside and outside, public and private. Image descriptions are one small part of that, and they’re easy to do.

Veronica Lewis wrote a fantastic article about how to write alt text and image descriptions on Instagram posts. It’s super helpful, and includes some useful definitions and context, like the difference between alt text and image descriptions, and what screen readers can and cannot read.

I learned a lot from this guide to writing image descriptions by Alex Chen. They offer some great tips for how to write good descriptions, with examples.

The above article lead me to Alex Chen’s Instagram account, Access Guide, which is full of resources for creating better digital accessibility.

Image: An Instagram post by access_guide. Black text on an orange background reads: If you post a photo with text in it, include all the text in the image description so that Blind people can access it.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: When I moved here, I arrived to find the kitchen counter full of plants my bestie had left for me. This is a spider plant I just potted up, a cutting from one of the plants she gave me and that I have kept alive for the past year. It’s a reminder to tend to the things that bring me joy.

Please also enjoy this beautiful call, the soundtrack to which I wrote this newsletter.

And that’s it until next week In the meantime, you can always find me on Instagram and Goodreads. Happy reading, everyone!

Looking forward to hearing about Solnit's New Orleans maps! I've been meaning to check out that trilogy but haven't had the chance yet.