In early March I had the joy of getting to hear K. Iver read from their stunning collection Short Film Starring My Beloved’s Red Bronco (a book I love so much I’ve read it twice since it came out). During the panel discussion, Joan Kwon Glass, who was in conversation with K. Iver, asked how they handled the solitude of writing—what did they do to balance the intense solitude that comes with writing poems?

As she spoke, I felt my whole body flame up in sudden rage—what felt like rage. What she was saying (what I heard her saying)—that writing requires solitude, that it is something we do alone—felt deeply, unequivocally wrong. It was like someone telling me the earth is flat. Incontrovertibly false.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the intensity of my reaction to this benign question. She was not making a statement about what all writing is, or what all writers do. Very reasonably, she simply said: I need solitude to write and sometimes it feels lonely. Does that happen to you? How do you deal with it?

I heard something else. I heard yet another iteration of a lie about writing that I have been telling myself for most of my life, that has been repeated to me, for as long as I can remember, in books, films, music, conversations, stories, and myths. The lie is that writing is something you do alone. The lie is that you can write alone. The lie is that writing happens in isolation.

Writing is social. It requires other people. It is of other people. Poetry, specifically, is after, among, and with. I have come to know (and what I know is always changing!) that poetry is the opposite of aloneness. It is the opposite of isolation. It is, by definition, a connective act.

None of this means that we do not need (or want) solitude—and silence—to write. Solitude and silence are not in opposition to sociality and connectedness. I’d argue that they are actually an essential part of sociality and connectedness. The question Glass asked was reasonable, generative. It was a question of methods and materials, of dailiness. She was not talking about the nature of poetry or of writing itself. I only heard it that way because I have become hypersensitive to this particular lie.

I believed in this lie—the lie of solitary writer, the artistic hermit—until sometime in December of 2023, when a desire to write poems emerged from a deep and growing place inside me. I followed that urge and my life changed.

In February 2024, after a month of writing a poem every day, I wrote one that felt different. It had a different weight. I read it out loud to myself. I thought: Is this something? And then I texted an internet friend, a fellow reader, writer, and lover of poetry, someone I admired, who I’d chatted with a bit but didn’t know well. “I just wrote this poem and I think it’s something,” I said. “Can I send it to you?”

As far as I’m concerned, that is the moment I became a poet (something I am still becoming, will always be becoming). In that moment, I acknowledged that I do not write alone, have never written alone, will never write alone. I had been trying to write alone for so long. None of what I wrote in all those years—age sixteen to thirty-eight—was what I needed to write. I had to let go of the lie to let the poems in.

That text flowered into a long-distance friendship that includes snail mail, a creative and regular exchange of poems, check-in texts, I’m-thinking-of-you texts, wowie-check-out-this-poem-I-just-read texts. Care, creativity, and curiosity. It is a friendship I cherish. It is one of the facts of my life that textures my poems.

I am of the world. I am in the world. For so long, I thought being a writer meant stepping outside the world. Finally, I understand: poems are conversation.

When my celebrity crush David Naimon, host of the incredible Between the Covers podcast, asks a question on the show, he often speaks for several minutes, and then, finally, says, “this is my very long way of asking…”

This is my very long way of saying that this month’s newsletter is a collection of snippets from conversations I’ve been having with friends, family, collaborators, trees, water, myself, poems, poets, grief, my dog, my house, ghosts, books, anger, silence, the sky, history. It is a messy mix of: “Look at this!” and “This makes me think of you!” and “I need you to listen to this!” and “That reminds me of!” and “This made me weep.” It is unordered and incomplete. It is how I am becoming a poet in the world.

Tree Parts

I spent most of March working on a wood project for my Visual Concepts class. We start all the projects we do with a materials exploration. The thing I kept thinking about, during that exploration, as I walked around the forest looking at trees, and counted all the things made from trees in my house, is that trees are the best at being themselves. They are so good at being trees. At the same time, they are endlessly transformable. Trees are stillness and change at the same time.

I’ve also been thinking constantly about syntax and tree syntax, about tree language and form. I collected a bunch of tree parts on walks—sticks, bark, twigs, branches—and started arranging them on a hemlock board. I had some hemlocks cut down on my land a few years ago and milled into lumber. This is one of the edge-boards, with the bark still attached.

I had a different idea for this piece, but as soon as I started playing with it I realized that I didn’t want to make it into anything. I just wanted to find a way to illuminate the beauty and the treeness of these tree parts. I was thinking about syntax and transformation and what it means to be separated from a whole. I was thinking about order and unorder and time and stanzas and death and rebirth and stitching.

Who knows if any of that comes through in this piece. It doesn’t matter to me, because I’m not making visual art with any particular agenda. I’m making it to play, to figure out what I think, to get messy with visual language, to learn new things about color and shape, to feel new strangenesses, to see what poems are born.

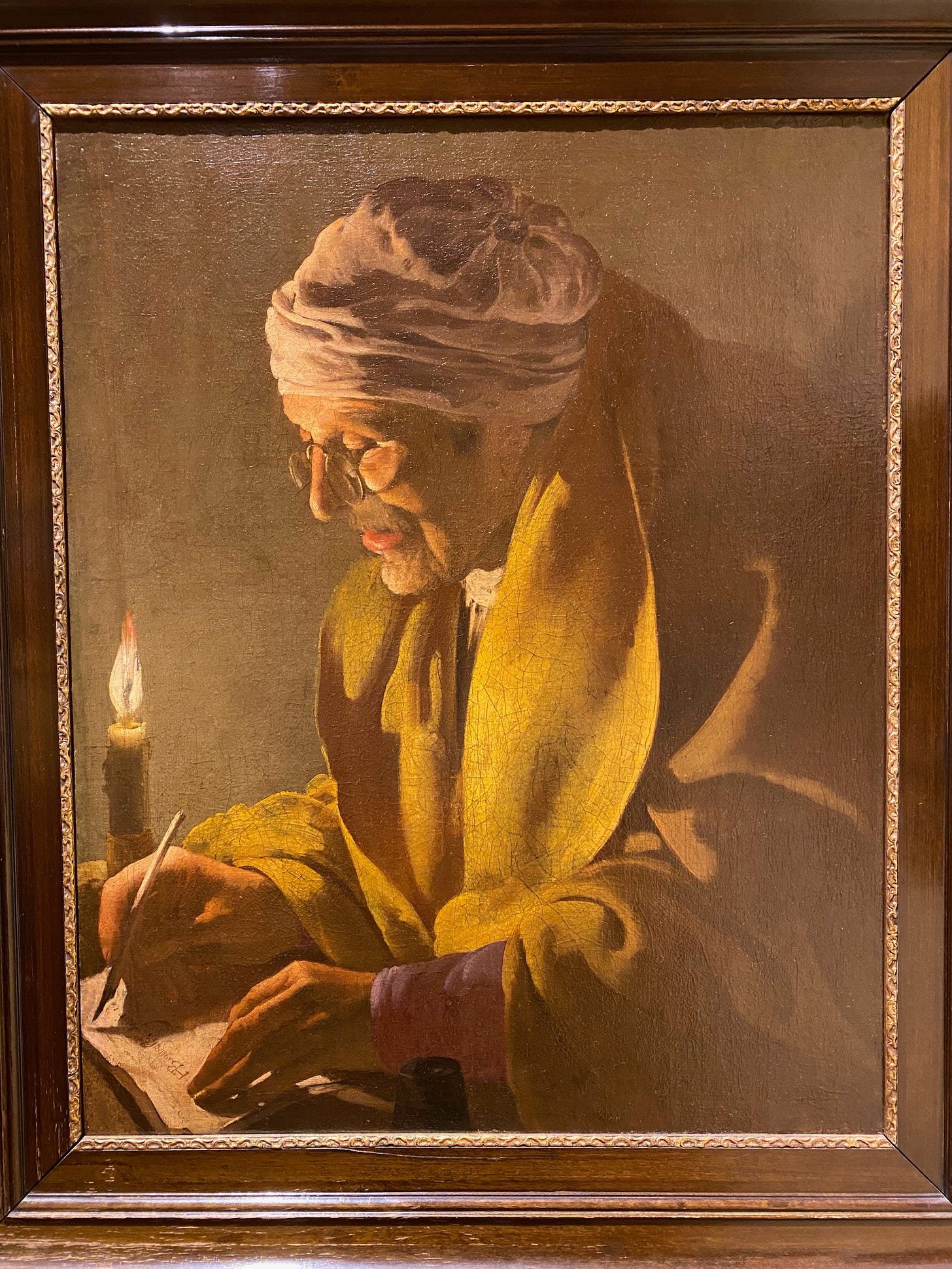

Man Writing by Candlelight

I have loved every assignment my art history professor has given us so far this year. One of them was to go to a museum (real or virtual) and write up a review of our experience. In addition, we had to find a piece of art from a time period/culture we studied in class and do a visual analysis of it. I went to the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA) and now I’m kind of obsessed with it. It’s free to everyone!

I was not expecting to fall in love with this Dutch painting from 1627 but here we are. It drew me to it from across the room. I spent a half hour looking at it and writing about it. It’s just such an intimate, familiar scene. I might not have a cap and robe just like this, and I usually have electric lights on when I write, but, in so many ways, I could be the man in this painting. His slightly parted lips. The way the light falls on his hands and face. His concentration. What can I say? I adore it.

This dude Hendrick ter Brugghen was an interesting painter. He painted a lot of musicians and scenes of secular life.

Morning in the Bowl of Night

I had no idea the SCMA had any Alma Thomas paintings, let alone that one would be on display. So when I saw this on the wall, I gasped. I love Alma Thomas. I knew I had read an ekphrastic poem about this very painting recently. I was pretty sure it was by Carl Phillips. I texted my friend Surabhi, with whom I’ve been reading Carl Phillips with this year, and she assured me that yes, that was right.

I went home and reread the poem, which is incredible. I had remembered loving it, and that I’d looked up the painting and loved the painting, but now both of these works of art feel like they are a part of me in a different way. These lines especially: “Lanterns in the trees, / there should be everywhere lanterns. Let the branches imitate / a crown. It should look like memorizing what a crown once was.” I can’t find it anywhere online but it’s in Then the War (a book of my life).

It turns out Carl Phillips wrote this poem for an anthology called The Map of Every Lilac Leaf, in which 40 poets respond to works of art in SCMA’s collection. Swoon. A hold has been placed.

Gender Feelings / Stag Dance / Tenderness

I have a lot of gender feelings. We all have a lot of gender feelings. Torrey Peters’s newest book, Stag Dance, is about gender feelings: messy, multidirectional, contradictory, uncomfortable, weird, scary, fun gender feelings. It’s a collection of four novellas in different genres. I loved it a lot. Peters uses genre to play with gender, to explore underbellies and interiors. The more I think about this book the more it astounds me. It’s funny and sharp and also overflowing with tenderness, especially the titular novella. Who knew the tenderest piece of fiction I’ve read so far in 2025 would be a novella set in an illegal logging camp in the early 20th century. I wept.

I listened to two interviews with Peters (who am I?!)—she was on The Stacks and Between the Covers. Both are absolutely fantastic. In The Stacks interview she talks about how she’s more interested in dismantling the trans/cis binary than than male/female binary. I am fixated on this idea because it comes through in her work, and it makes her work feel both exciting and honest. She’s not saying there are no differences between trans and cis people. She’s saying that everyone has a relationship with gender, and those relationships are often weird and messy. Trans people are forced to confront those relationships in ways that most cis people aren’t.

On Between the Covers she talked a bit about how she thinks some of her work is dangerous—that it could (will) be used as ammunition for anti-trans rhetoric and legislation. She’s referring to one specific story, The Masker, and she talks about how she feels like the risk is worth it because it will also be read by trans people who need it. I rarely hear authors talk about this kind of risk-taking in art, and I really appreciated it.

I was thinking about this when, a few days after I finished the book, I read this piece by trans writer and journalist Roz Milner, about reading The Masker 10 years ago when Peters self-published it, and reading it again now. Art is unpredictable and powerful.

Poetry as Field

One of my favorite BTC episodes I listened to in March was the one with Diné poet Jake Skeets, about his gorgeous book Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers. I cannot stop thinking (writing, walking, wrestling) about what he says about the field in poetry. I scribbled down so many notes:

“There isn’t really any free verse [in the United States], and the absence of a true free verse is related to the notion that we need to contend with the field.”

“The imperial mindset[ in relation to free verse] is this idea of conquering the page with your own structures…When we approach free verse there is this idea that the page is this open thing that we can then conquer.”

“When you’re looking at a field, you’re not just looking at wildlife, you’re not just looking at plant life, you’re not just looking at nature, you’re looking at time.”

He talks more about the field in this short and beautiful essay. The field is also woven through Ariana Benson’s stunning collection Black Pastoral. It contains several poems titled ‘Love Poem in the Black Field’, like this one. See also: Tyree Daye.

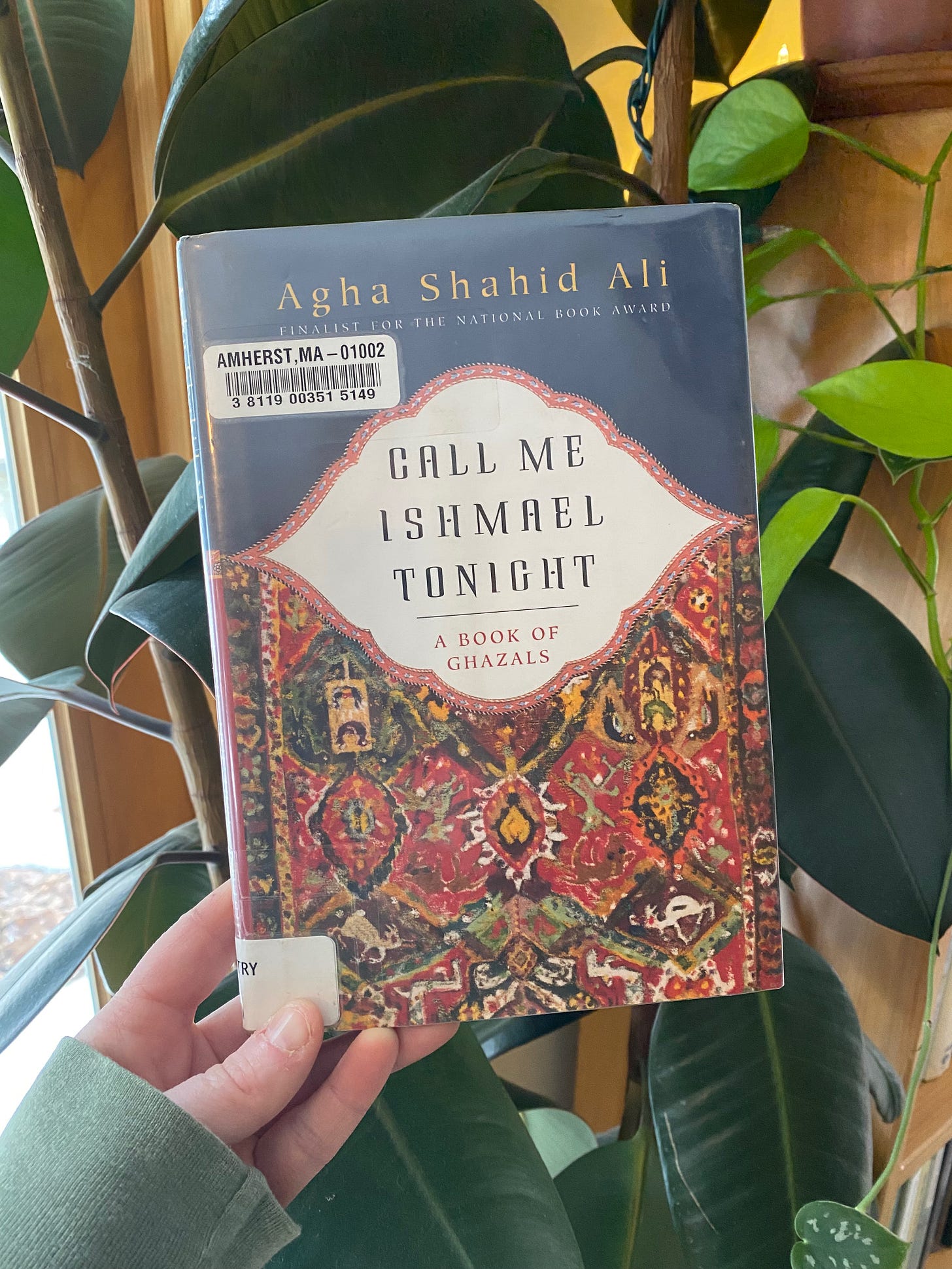

Constant Longing

One thing about me is that I love ghazals. The best poetry collection I read in March was Call Me Ishmael Tonight, a collection of ghazals by the master of ghazals in English, Agha Shahid Ali. This poem is—well, this poem is my heart now:

I Have Loved I must go back briefly to a place I have loved to tell you those you will efface I have loved.

I wrote about the book exuberantly here. I also posted to my stories about how profoundly it moved me, and how mysteriously and bodily I experience the ghazal. A few weeks later, Ravishing DisUnities, the anthology of ghazals that Ali edited, arrived on my doorstep. A sweet internet friend listened to me praise and weep and exclaim about ghazals and then sent me the book. I am profoundly moved, again.

I haven’t read it yet, but I did read Ali’s one page primer on what ghazals are (and aren’t), formally. “What defines the ghazal is a constant longing,” he says.

The Seasons

My aunts invited me to see an opera with them and I don't know how to write about it. The Seasons (libretto by Sarah Ruhl and co-conceived by Anthony Roth Costanzo) is a contemporary opera about a group of artists on a retreat on a farm. Two of them, The Poet and The Painter (both astonishing countertenors) fall in love, but really this opera is about climate disaster, about weather (external, internal, catastrophic, climatic), about making art and loving and caring for each other though the end of the world. I’m not sure I’ve ever been so moved by a piece of live theatre in my life. It was like being inside a poem except the poem was people on stage using their bodies to sing, and move, and dance.

The music is Vivaldi—some arias and ensembles, but mostly The Four Seasons. The concertos are out of order, though, as the seasons are disordered. I’m still thinking about the strangeness of encountering such familiar and beloved music in such a new way, the shock and buzz of it. I’m also still thinking about the poetry, the dancing, the stunning set design, and the singing. I don’t know anything about opera. This was basically my first one. That human bodies can do this, make this music—astonishing.

I felt pierced by the whole thing, especially the ending, which still haunts me.

Jenny George

The visiting poets series at the Smith College Boutelle-Day Poetry Center continues to be an absolute dream. Last week I saw Jenny George, a poet I haven’t yet read (oops!) but whose book After Image I immediately bought because she was incredible (and also it was published by my beloved Copper Canyon Press). In the conversation after the reading, she said that “the project of empire is to deaden the senses” and the project of poetry is to “awaken the senses.” I’m listening, Jenny George.

Afterwards I told her how much hearing her read and speak had meant to me (I think I am maaaaybe getting better at talking to authors?!) and she asked if I was a poet, and I said yes, and then she asked if I was a Smith student, and I said no, I’m just a poet in the world, but that I had returned to school recently after almost 20 years. She was so warm and excited and generous, and then as I was leaving I looked down at how she’d signed my book and burst into tears.

Poets are the real deal.

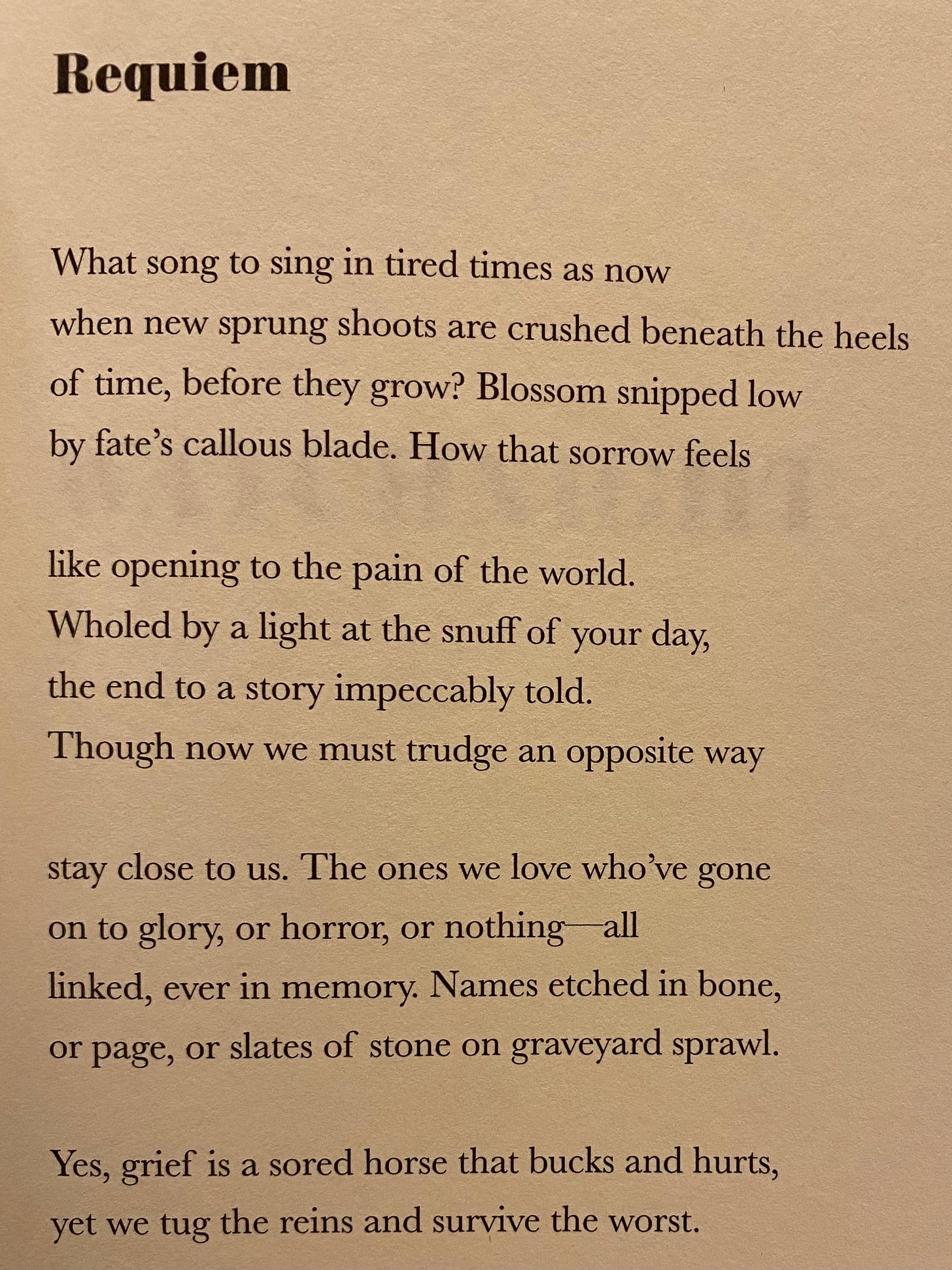

“Yes, grief is a sored horse that bucks and hurts, / yet we tug the reins and survive the worst.”

I can’t stop reading this poem from Cyrée Jarelle Johnson’s collection Watchnight, which I reviewed here. You can also read it here.

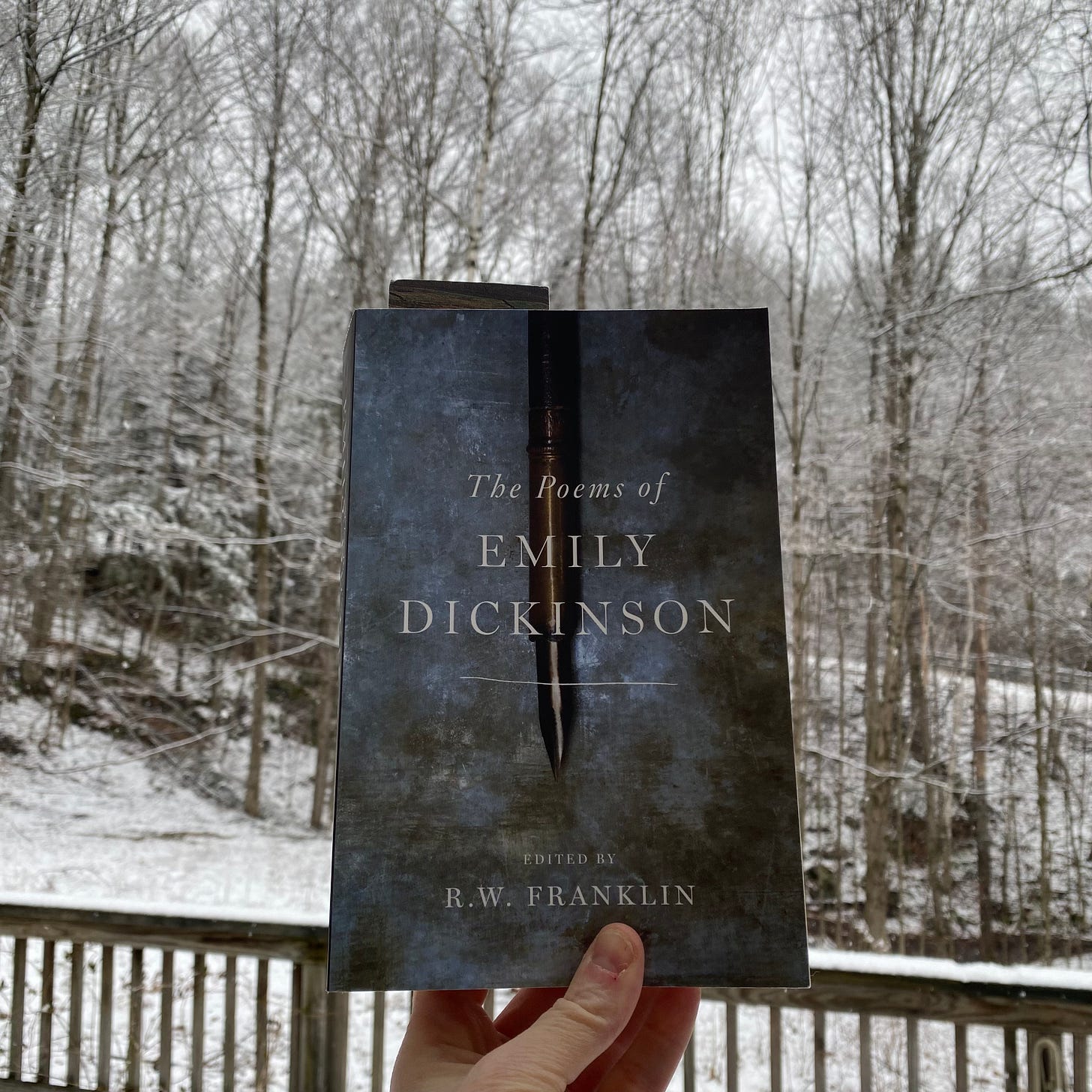

Emily Dickinson

My in-person book club is reading Emily Dickinson in April! I’ve never actually read her, beyond high school English and the few famous poems of hers that circulate around the internet. If you’re surprised, I am too.

We didn’t pick a specific book—we’re all just going to read what we want, and then discuss. I used this as an excuse to buy this 700-page chonker edited by R.W. Franklin. I started at the beginning and I’m reading a bit every day, and guess what? I’m super into it.

I’m not that far into her body of work yet, but there is a direct throughline from her to Mary Oliver. I feel it in my chest. The way she writes about death and flowers and bees feels intimately and immediately familiar to me. There’s a sweetness in her poems, an easy delight, that hides, I think, some of the murk—grief, loneliness, oh shit, we’re all going to die.

I told a friend I think I’m probably preordained to like Dickinson, and she said, “I agree.” Here we are. Happy to be here.

A body is something that needs support

During the Trans Rights Readathon I listened to How to Tell When We Will Die by Johana Hedva. It’s a fantastic essay collection about disability, illness, pain, writing, kink, queerness, gender, art, care, and the stories we do and do not tell ourselves about all of these things.

The most revelatory part of the whole book, for me, is this one sentence from the introduction, in which Hedva shares their definition of what a body is: something that needs support. Or, shortened, something that needs. I cannot stop thinking about this. I’m thinking about it in relation to the bodies of trees, work, the ocean, plants, creatures, my own self. What can have a body? What can’t have a body? What does a body of water need? A body of work? The body politic? This one sentence has completely changed the way I think about bodies, need, and support.

“It seems to me she’s mostly talking about death.”

I will never forget where I was (a Stop and Shop parking lot) when I heard Ross Gay talk about Mary Oliver on the audiobook Wild and Precious. I can still hear his voice as he explained that he thinks she’s often misconstrued as a sweet nature poet. “It seems to me she’s mostly talking about death,” he said. I think about this most days.

The last time I sent out a newsletter, I was listening to Ada Limón on Between the Covers. At one point David Naimon said: “This notion of death only leading to praise, and part of the reason why I wanted to bring up death in order to complicate the notion of joy and even the notion of praise, is that it feels like earnestness, wonder, and joy are easy to make fun of or look down on, perhaps because of the most facile versions of these things which we also see in the world.”

My April Year of Mary book was American Primitive, published in 1983. In maybe my favorite poem in the book, ‘Blossom’ she writes: “What / we know: that time / chops at us like an iron / hoe, that death / is a state of paralysis. What / we long for: joy / before death, nights / in the swale—everything else / can wait but not / this thrust / from the root / of the body.”

I’m just a poet in the world, walking through forests, thinking about death, listening to “this thrust / from the root / of the body.”

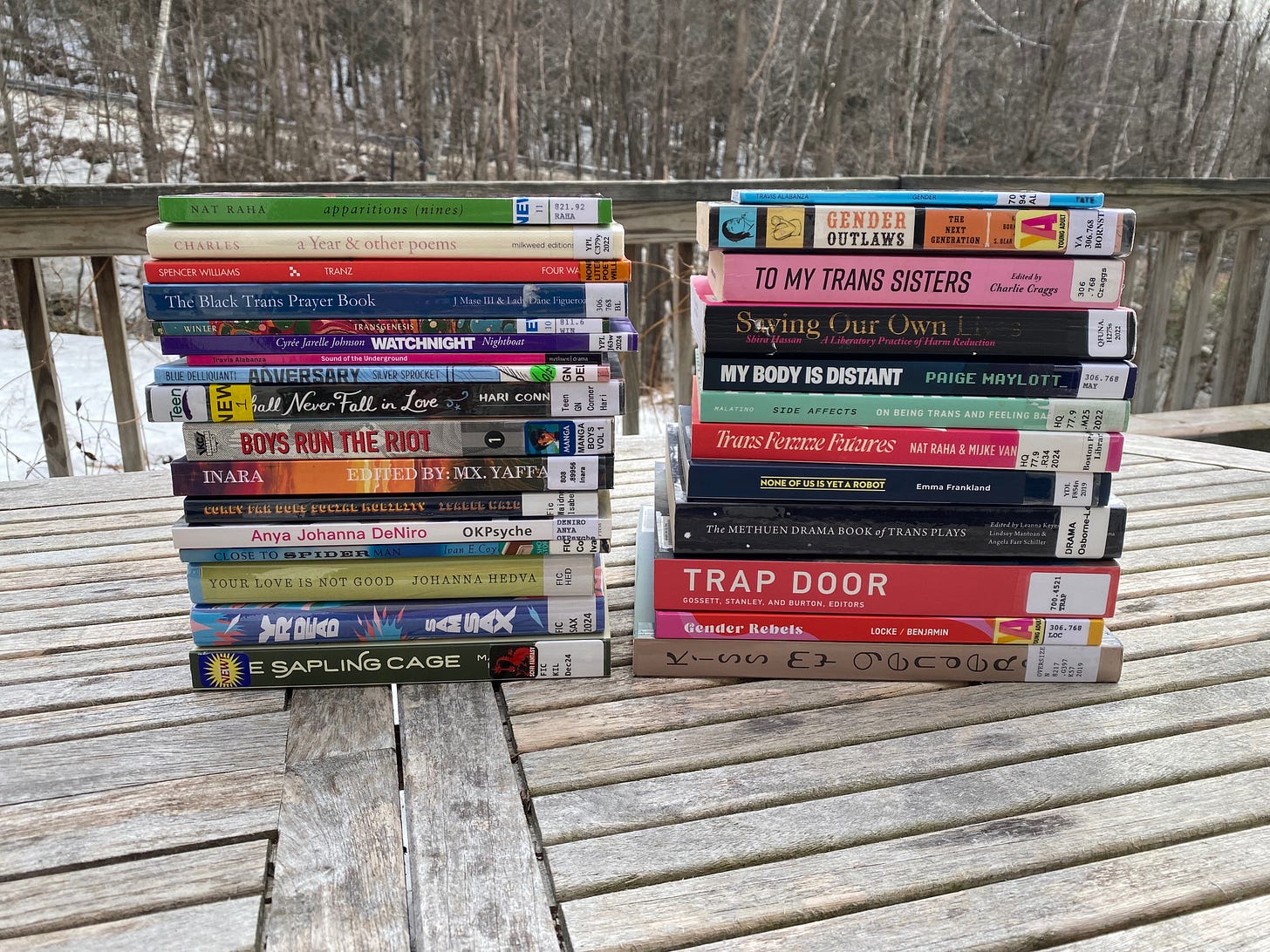

The Trans Rights Readathon

I participated in the third annual Trans Rights Readathon and it was wonderful, as it always is. I read 23 books (including 4 picture books), many of which I reviewed on IG.

I also created a series of curated lit spreadsheets with detailed information on some of my favorite poetry and queer and trans lit. I offered these spreadsheets in exchange for donations to trans justice orgs, mutual aid funds, or individual folks. Collectively, we raised $2,210!

This is not enough but it is something. People all over the country (and world) donated to their trans friends, mutual aid funds for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated trans folks, gender-affirming care fundraisers, local LGBTQ+ centers, and more. I donated to Project Rainbow Turtle.

I loved almost everything I read for the readathon, so here are three highlights:

apparitions (nines) by Nat Raha (2024): This collection set my language joy organ alight.

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor (2017): I really loved this tender, sad, searching book. And I love talking about it with my book club!

Sound of the Underground by Travis Alabanza, co-created with Debbie Hannan (2023): I loved the way this play made me think about process and impact a creative work has on its makers.

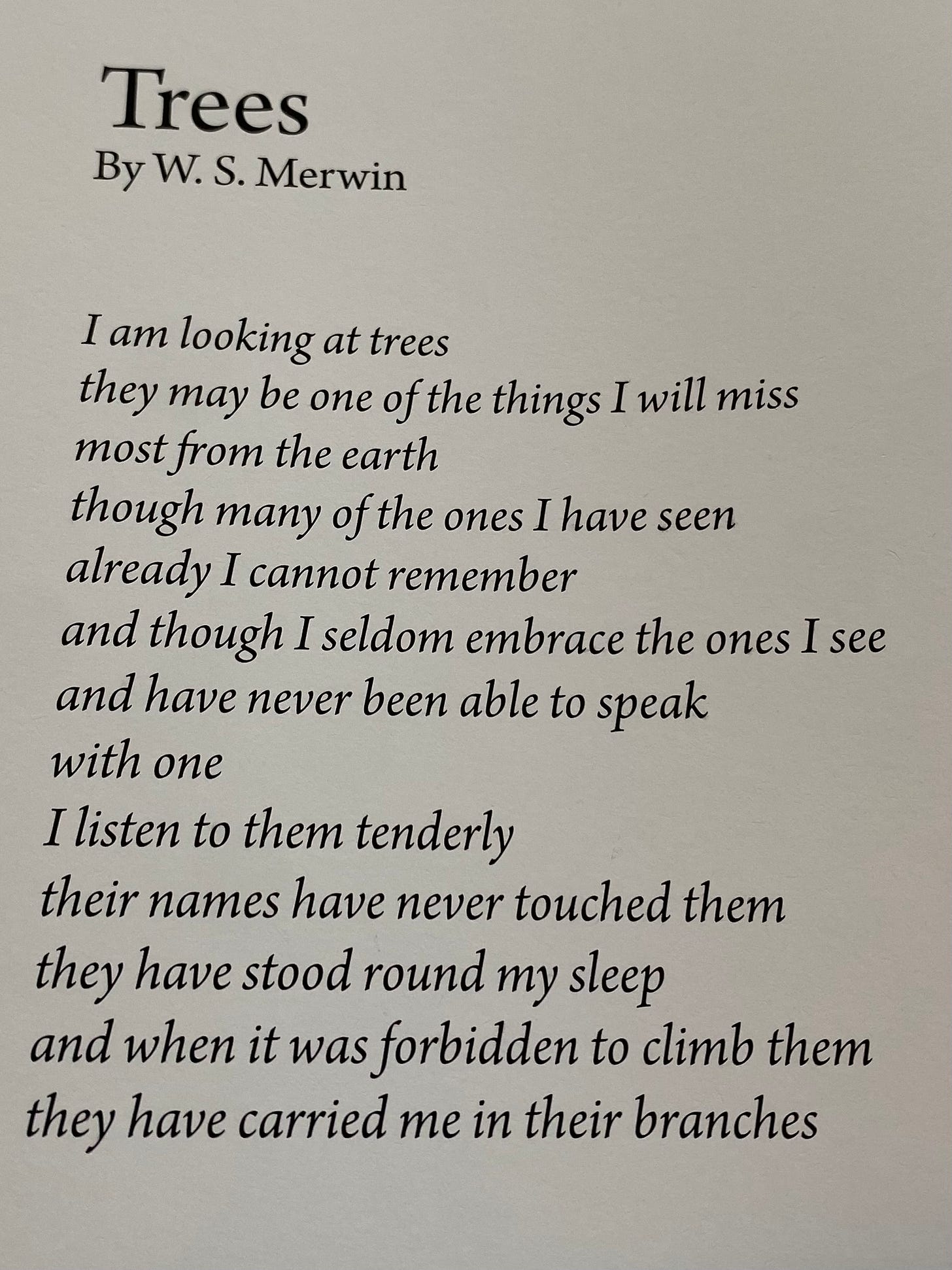

“their names have never touched them”

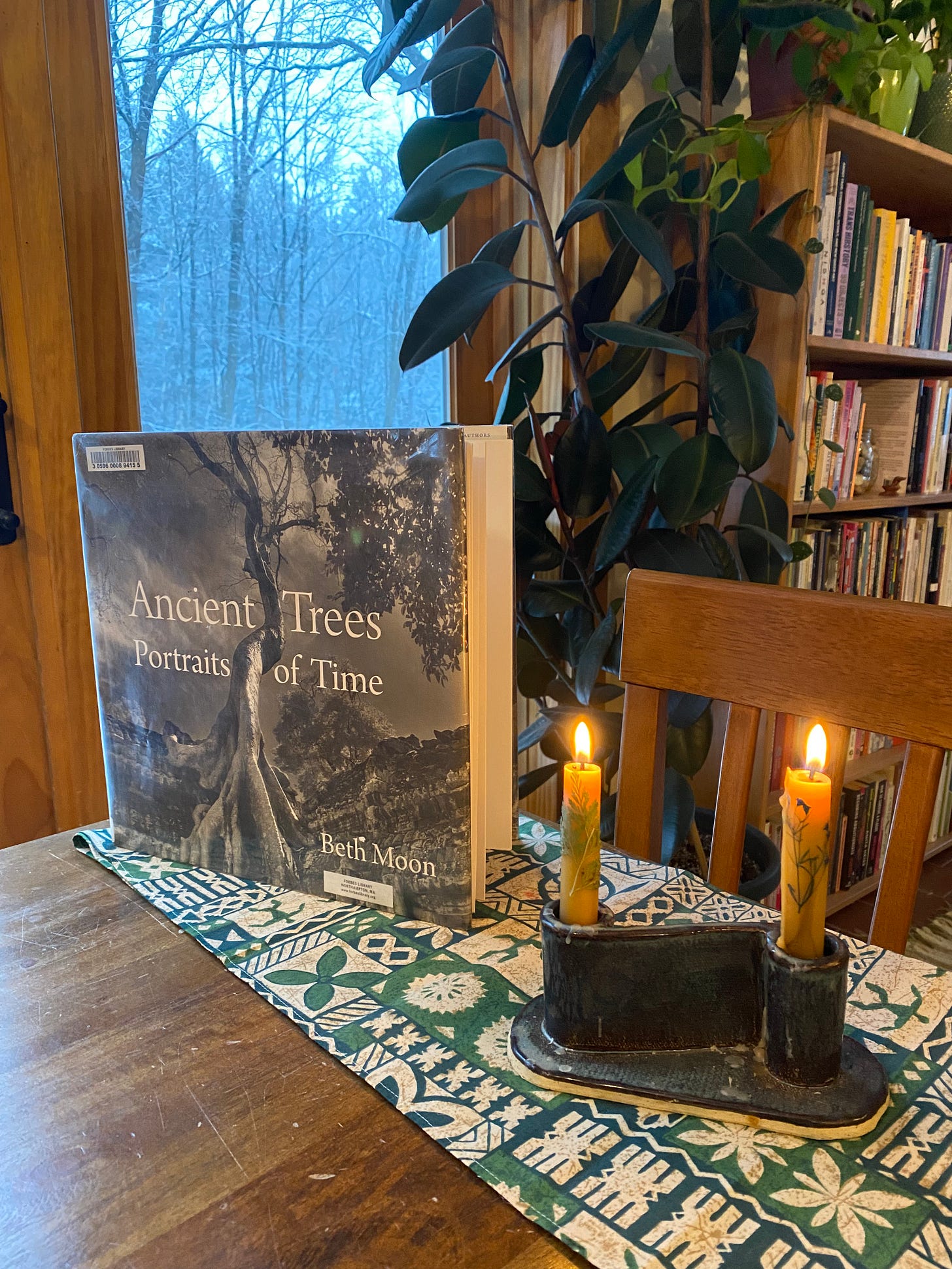

I encountered this poem in a book of photographic portraits of ancient trees (more on this below), and I am still encountering it.

Intellectual Overwhelm (Complementary)

If you follow me on IG you know I have fallen hard for art history. I can’t remember the last time I felt so intellectually excited and alive. It might be a first. The art history class I’m taking is endlessly frustrating (so much European art) and I’m deeply critical of the disipline as a whole. After practically every class I’m buzzing with ideas and connections and anger and awe. I see so many ways this history relates to poetry, to language (which is really my first and forever love), to literature, to how we read and understand the world. I feel like there might be some meaningful work for me somewhere in this realm.

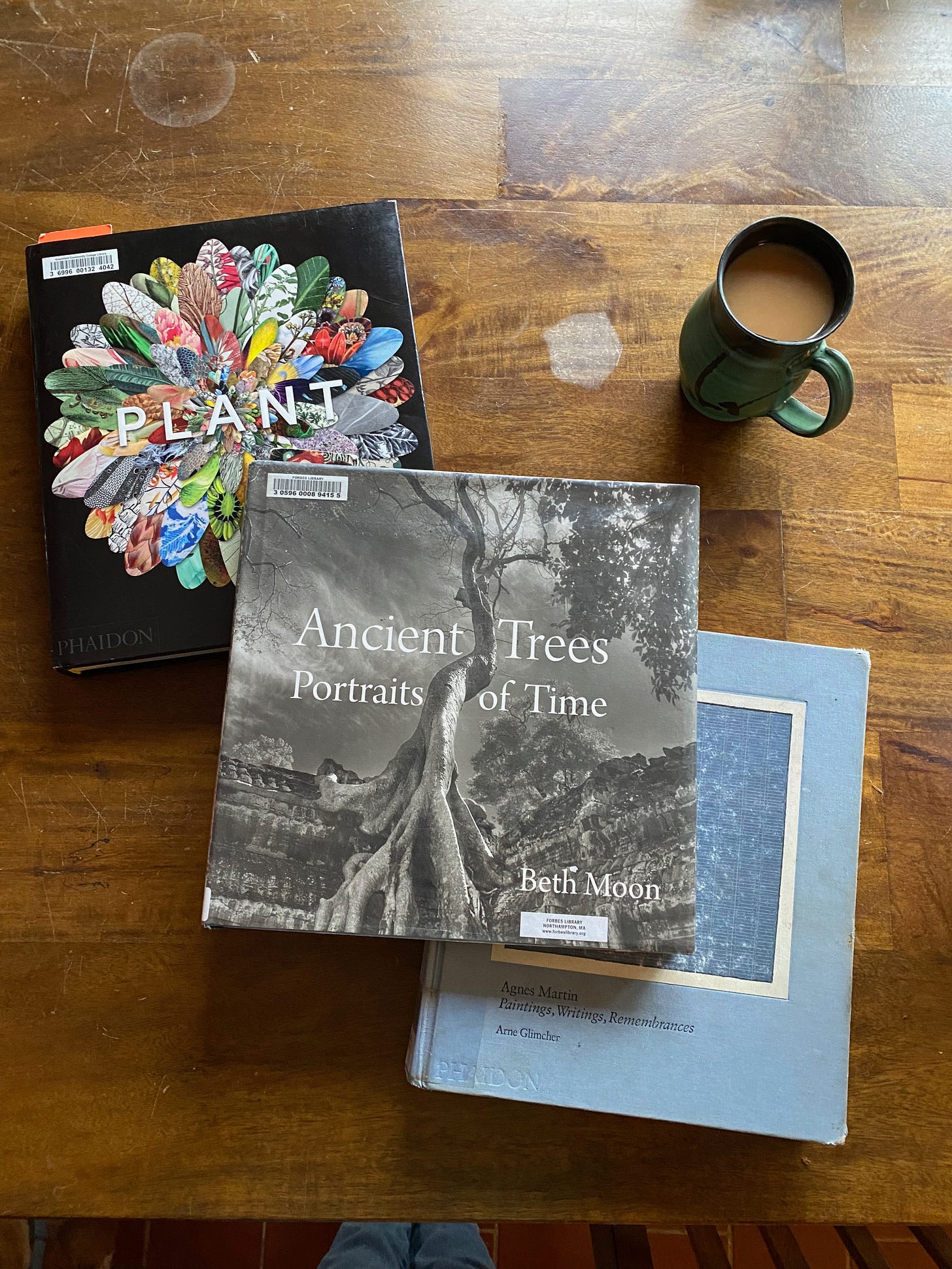

I picked up Plant, a huge book of botanical art at the GCC library. I’m reading a little bit each morning and thinking about beauty, colonial ecology, and what’s invisible (see below). I watched the fantastic documentary Black Art: In the Absence of Light, which, in part, focuses on the exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art, curated by David Driscoll in the 1970s at the Brooklyn Museum. The exhibition book is currently waiting for me at the library. I signed up for classes in the fall (more art history, a course on reading plays, a geology class about the history of the earth). I love being a student more than I ever dreamed possible (the last time I tried doing this I was so depressed I can barely remember anything about it).

I have a lot of feelings about higher education and also I believe that thinking is a pretty big deal. We need to create all kinds of spaces where all kinds of people get to think, especially right now (especially always) amidst so much censorship and repression. I am grateful to have found—to be creating—such a place.

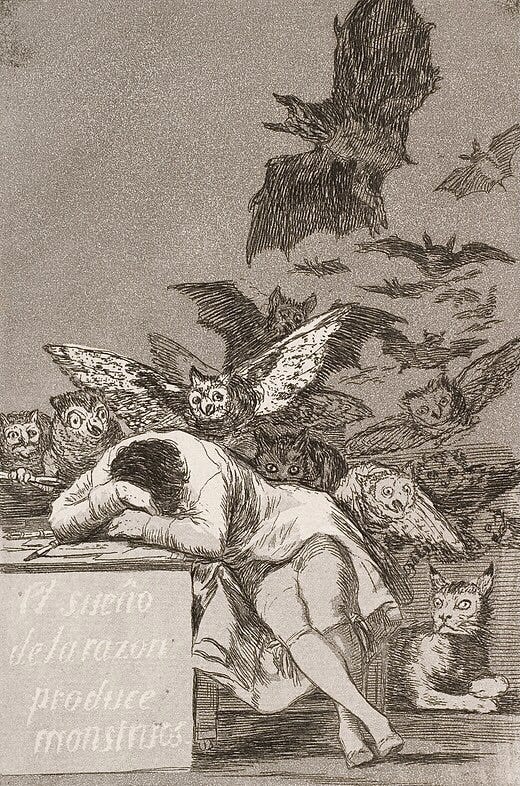

(Invisible) Art Histories

We had to create an imaginary museum exhibition for our midterm project using pieces of art we’d studied in class. Mine looks at what is invisible in art, the stories that aren’t told, and the way that, throughout history, empires have used art to pursue their own oppressive and colonial agendas.

I am fascinated, in a way that feels quite urgent, about what we don't see when we look at art. It has been easy for me to apply this "what's invisible" lens to art made by and for massive colonial empires. But I think it’s important to look at all art through this lens. I fell head-over-heels for these eerie, satirical Goya prints. I love how weird they are, and, of course, how political. What happens, though, is that the dissent becomes the surface So what’s beneath the surface? What did Goya not see clearly enough to be able to critique? This question of the invisible haunts me.

Earlier this year I read Coexistence by Billy-Ray Belcourt. There’s one story in which a Cree professor of poetry is talking to his white partner about how some of the poetry his students write is infused with "structures of whiteness" and his partner gets annoyed with him. I think about this almost every day. The professor isn't even saying that this poetry is bad. He's pointing out something in it that is invisible to "the expected reader" (Elaine Castillo's phrase). This is related to thinking about invisibility in art. Looking at what's not there makes art bigger, richer, truer. There is always something missing, something that haunts.

Forests are made of time

I’ve been walking and thinking (read: writing poems) about forests. I am thinking about how they are made of time. I walk through the woods and encounter death, decay, new life sprouting, old trees, dying trees, young trees. I am starting to think this is one of the most profound and beautiful truths about forests.

Have you ever seen a tree that was just a tree? Have you ever seen a tree without moss or lichen or some kind of fungi growing on it? Trees are communities.

The other day I was walking in some woods at a state park just over the Vermont border, and I encountered this tree that had fallen down into a pond. Nessa and I stood on the log and looked out at the gently rippling water, the ice across the pond that hadn’t melted yet. I know it was just a dead tree in a pond, but it felt sacred to me. These are the moments I’m holding close.

Hanif Abdurraqib

I often screenshot what Hanif Abdurraqib posts to his IG stories. He’s a generous and rigorous thinker and writer. His words often awaken and clarify some feeling or instinct I’ve been struggling to express. Here’s something he said after Mahmoud Khalil was abducted by ICE. I’m sharing it here, in part for myself, as a reminder, so that I have this wisdom to return to when I need it:

Outside of the fact that I am exhausted by people needing personal stakes to care about anything, I also think the "if you tolerate this, you will be next approach" is both flawed and also harmful when discussing Mahmoud Khalil. I do understand it, in the broadest sense, government overreach can absolutely eventually impact everyone living under said government. But this specific gesture of overreach actually will not impact everyone the same way and there won't be a point where it will because this approach has very specific targets and it being carried out for a very specific reason and is a very specific exercise in fascism with very specific goals.

And I think it's important to name and delineate these things for a couple of reasons, the first reason being that there are in fact some of us who are just not going to be in the scope of this specific weapon. Some of us in the same way, and some of us not at all. And I think to flatten this experience to "this could happen to you or someone you love next" doesn't feel accurate and also kind of flattens critical thought, when I think it's actually useful for people to understand what individual privileges they hold in relation to those people who this COULD reasonably happen to next, and then align their actions and the risks they are willing to take with those privileges.

I just want people to consider the limits of "this could happen to you next" - and trust me, I fall into that approach too, I'm trying to be very intentional about what brings me to action because I know that what usually does bring me to action is in opposition to the feeling that I could or could not be "next" - I don't fight for my neighbor because I don't want to see what's happening to them potentially happen to me, I fight for my neighbor because I don't want to see what's happening to them continue, or because I know it is a symptom of some other, larger happening and it doesn't matter if that larger happening descends on me specifically or not.

I am not so naïve as to think that the violence this government is carrying out with such horrific glee will not come for me too. But I’m also acutely aware that some of the privileges I hold (white, cis, generational wealth) are incredibly protective. I'm a queer woman, but my life as a queer woman is not in danger in the way many other people's lives are in danger. I care about what is happening to Mohamed Khalil and Rumeysa Ozturk and others because it is a horror that should not happen to any human. I care about the vicious and relentless attacks on trans people because I want those vicious attacks to stop. I am scared. When I act against the horrors, I don't want to act in anticipation of some future violence against me. I act because of the right-now violence being done to people I love, people in my community, people who I do not know. That's what I am holding on to. For me it is much much more clarifying than "this could happen to you."

The Five College Collections Database

I’ve been to SCMA twice in the past month and I am a little bit obsessed. I’ve also learned that you can request to see any object in their collection. This is, apparently, true for all of the college art museums in the Valley. You can just email them, tell them you want to look at this 15th century print, for instance, and make an appointment. I will be making use of this resource. I am not over this and never will be.

Thinking with Trees / The Soul of a Tree / Ancient Trees: Portraits of Time

Jason Allen-Paisant, Thinking With Trees (2021)

In sparse, woody, meandering, walking, spacious poems, Allen-Paisant thinks with trees. He thinks with trees about treeness and humanness and Blackness, about time and water, about walking and being still. He thinks with trees about what it means to move in the forest as a Black man, about what it means to love landscapes where he is not expected, about violence and refuge.

Many of the poems take place in the woods near where he lives in Leeds. They are populated by white people who are more concerned with their dogs than with his welfare and humanness. They are populated by threats (again, mostly white people), but also by squirrels, rivers, tree kin, ancestors. They also recall Allen-Paisant’s hometown in Jamaica, and the different textures, histories, languages, and legibilities of the being in the woods there. I wrote more about this book here.

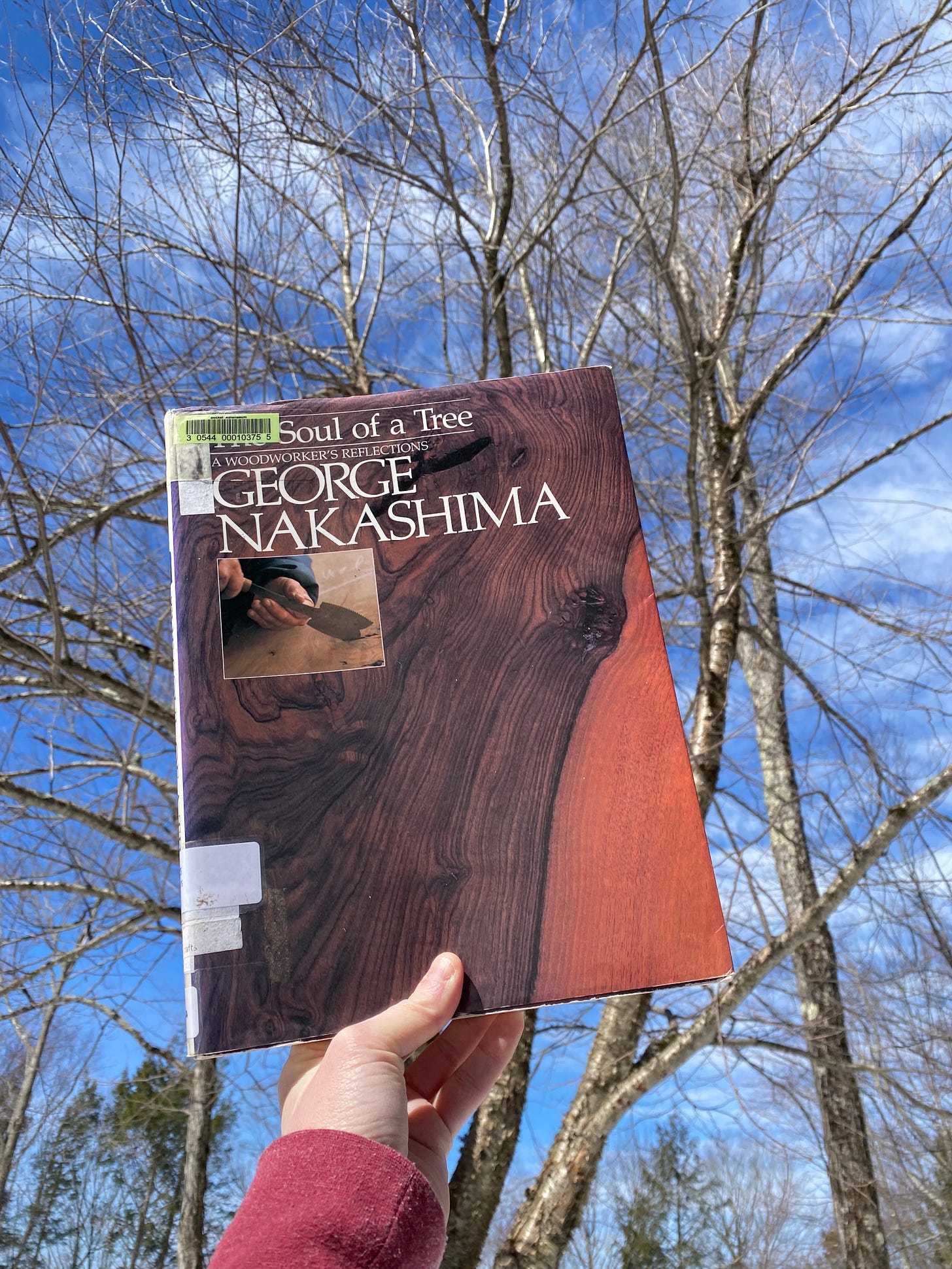

George Nakashima, The Soul of a Tree (1981)

Last month, I read a picture book biography of George Nakashima, which made me want to pick up his book, and I’m so glad I did! Nakashima was a Japanese American carpenter, craftsman, furniture builder, and designer. He founded George Nakashima Woodworkers in New Hope, Pennsylvania, which is still run by his family today.

This book is part memoir, part guide to carpentry, part photo tour of Nakashima’s New Hope shop and property. In the first part he writes about his childhood among the trees of the Pacific Northwest, his travels in Paris, Japan, and India as a young architect, and the opening of the New Hope studio after World War II. He then writes in detail about trees, lumber, and his relationship to wood. The final section, full of photos and sketches, details some of his design principals and philosophy, and the the techniques and tools he uses.

This book is a celebration of trees and wood. Nakashima talks about making furniture as giving trees a second life. And while I’m not sure I agree with this—it feels very human-centric—I found his ideas about care, materials, and the spirit and nature of wood so compelling. Sometimes, he says, a board will sit in the shop for years before he comes up with the right piece of furniture to make with it. He talks at length about matching the wood to the final piece, about listening to and looking at each tree, each board, and using that knowledge to guide what eventually gets produced. He values slowness, beauty, and craftsmanship above commercial production.

This book is full of his sketches of trees, lumber, and forests, as well as design sketches for chairs and tables, different kinds of joints, etc. It is such a loving work. It made me think so much about how we relate to the stuff of our world: not just trees as living, breathing, beings—but trees in their afterlives as wood. What does it mean to honor the non-human and also the non-living(?): wood, stone, water? Nakashima writes from a place of deep care and curiosity for the materials he transforms. What would it look like if this were the norm rather than an aberration? I loved thinking alongside Nakashima and his art.

Beth Moon, Ancient Trees: Portraits of Time (2014)

This is a stunning book of portraits of ancient trees. Moon traveled across many continents to photograph these incredible and ancient beings—ancient yews and oaks in the UK, sequoias in California, dragon’s blood trees in Yemen, baobabs in Madagascar, and more.

I cannot explain how gorgeous these black and white portraits are. Happily, you can see them here! They are, unquestionably, portraits. They are not scenic photos or landscape photos, but, rather, portraits that capture some small bit of the essence of these unnamable, uncontainable trees. Many of the trees are huge (hundreds of feet across or hundreds of feet tall), yet the portraits are intimate. They convey scale as well as specificity. Many of these trees are also almost unimaginably old—a 1,200 -ear-old yew, a 2,500-year-old giant sequoia, five-hundred-year old oaks.

I’ve been thinking a lot about time, and especially how forests are time, and I love how the title of this book points to that. The all-at-onceness of trees. How time and place are inextricably linked. Time, like the roots and trunks of trees, like the light filtering through their leaves, like weather in their branches, has presence, is specific, connected to land and what happens there.

This is all to say these photographs stunned me and moved me and made me so sad and filled me with wonder. I can’t believe we share the planet with beings like this. I want us to do a better job of loving them.

Women’s Things

“Our culture is in our tools, our shelters, our boats, our clothing, everything we make to live.” —Rosie Okpik

I saw this print last weekend and fell in love with it. It’s the piece that’s been haunting me all week. From the gallery tag: “The Pangnirtung print shop was founded in 1969 with support from the Canadian government, and it has published work by Pangnirtung artists since the early 1970s. Rosie Okpik's image of tools and clothing on a sealskin-drying rack emphasizes the importance of cultural knowledge and expertise: "We take great pride in these things we make by hand. They show how we can survive as a people."

Audre Lorde

I reread The Cancer Journals for the Queer Your Year book club. It’s only 69 pages, but it’s so rich. I needed it. I am grateful for Lorde’s words, her work, her thinking, her life.

“My work is to inhabit the silences with which I have lived and fill them with myself until they have the sounds of brightest day and loudest thunder.”

“For those of us who write, it is necessary to scrutinize not only the truth of what we speak, but the truth of that language by which we speak.”

“I have found that battling despair does not mean closing my eyes to the enormity of the tasks of effecting change, not ignoring the strength and the. barbarity of the forces aligned against us. It means teaching, surviving and fighting with the most important resource I have, myself, and taking joy in that battle.”

Artemisia Gentileschi & Feminist Art Lectures

My friend Mia turned me onto this series of feminist lectures. I rented one about Artemisia Gentileschi and it was so good! We spent about 20 minutes talking about her in art history, so listening to an entire two-hour lecture on her life and work was extremely satisfying, to say the least.

You can check out the whole archive here. They cost about $12 to rent so I can’t watch every single one, but I will definitely be checking out a few more. If you know of any free lectures like this about art history or related subjects, please let me about it!

What Will You Do?

In a recent essay for The Nation, Kaveh Akbar wrote:

I know it is absurd to write about my cat with the same machine I use to write about genocide. But I am yoked to my subjectivity. I do not have one brain for thinking about a rubbled Gaza and another for thinking about my gentle cat wheezing through the night. There is, in every moment, an at-once-ness that language cannot accommodate. You will, I hope, forgive me my instruments.

It’s a beautiful essay and it ends with a question: “What will you do?” It’s not a vague question. He’s asking you—me—specifically. What will you do? The truth is that I don’t know. I want to be able to tell you exactly what I am doing and will continue to do. But I don’t know. There are, of course, the small what-I’m-doings: Speaking and writing. Showing up to a protest for Palestine in the rain. Calling my elected officials. Supporting people doing work I care about, with money and/or time.

But the much bigger What will you do? is a question in process. It does not feel good to admit this, to not know. But this is the truth: I am doing what I can, which is not enough. I have not stopped asking myself the question and I never will.

“If you love someone, tell them—the planet / is dying.”

These lines are from Cyrée Jarelle Johnson’s poem ‘Earth, Earth’ and they have been ringing inside me for weeks.

My Tree

I’m reading House of Light by Mary Oliver and the other day I read the poem ‘The Oak at the Entrance to Blackwater Pond’ in which she describes an oak tree she loved that was struck down by lightning. “But, listen, I’m tired of that brazen promise: / death and resurrection,” she says.

“what I loved, I mean, was that tree— / tree of the moment—tree of my own sad, mortal heart—”

Wishing you all sweetness and strength, as ever.

Thanks for sharing the link to Project Rainbow Turtle. They are doing incredible things and the logo is really powerful.

I am currently caught up thinking about the through line between Emily Dickinson and Mary Oliver! I never thought of them as connected, even though I read both of them fairly close together one year, and now it feels so clear to me. The way they lived, their settings, the BEES my goodness. Thank you for telling us about it it and I’d love to read more about what you see between them if you ever feel like it. Also, I really enjoyed the show Dickinson—the first season is a little eh on race but I think improved on that front with a more diverse writers room in later seasons, so that’s my caveat in case you watch. But it’s a super imaginative show and I love that it presents a very different case for what Emily might have been like.