Greetings, book-devourers and treat connoisseurs! Yesterday a turkey vulture landed in my yard. I see them flying all the time, but I’ve never seen one up close, just sitting around with its wings folded up. They are so big!

I know I’ve mentioned how much I’ve been struggling to read sci-fi and fantasy since the pandemic started. These are the genres I grew up on. They have always been constants in my reading life. Now my brain cannot compute. Drop me in outer space or a fantasy kingdom and I am lost and bored. I don't know if this is a permanent shift (I hope not) or if eventually it’ll go away (please). I do know I’ve tried to read hard SFF over and over again in the past six months and it’s not working. I crave it, but I as soon as I get it, I don't want it.

So I am immeasurably grateful for books like these three: a little bit magical, a little bit speculative, a lot weird, and somehow, for me, right now, just right. They’re all set in this world, and they’re all centered on the emotional lives of the characters. But there are also moon colonies! A volcano suddenly emerging in Central Park! Time travel! A whale who transforms into a man so he can be with the woman he loves! And a whole bunch of other wonderful, fantastical, magical, futuristic things. I used to be able to lose myself in mythical kingdoms and spaceships. Until I can do that again, I’m reveling in the books that, though grounded in the complicated realties of being alive on this planet, at (mostly) this time, remind me of the wondrous possibilities of the human imagination and inject a little bit of magic (maybe) into my reading life.

The Books

Backlist: When the Whales Leave by Yuri Rytkheu, translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse (Fiction, 1977, English translation 2020)

I bought this book on a whim last fall because I love Milkweed Editions. When I picked it up on last month I was not expecting it to be a new all-time favorite. I love this book as much as it is possible to love a book. It is a fable with teeth and claws and heart. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t think about it.

Yuri Rytkheu was a Chukchi writer who wrote in both Russian and his native Chukchi. The Chukchi are an Indigenous people from the Chukchi Peninsula in Eastern Siberia, on the Bering Sea. Rytkheu is considered the father of Chukchi literature; several of his many works have been translated into English, and I cannot wait to read them.

When the Whales Leave is set in the Arctic homeland of the Chukchi people. It begins in some distant time, when the world was still new. Nau, a young woman, lives among the grasses and the ocean and the creatures. The writing throughout this novel is stunning; I am in awe of the translation. Here’s a passage from early in the novel:

Nau was fast breeze, green grass, wet shingle, high cloud, and endless blue sky, herself and all these things at once.

She had never yet thought of herself as separate from those who dwelled in ground warrens, or nested on cliffs, or crawled in the grass, nor thought of herself as different from them. Even the sullen black rocks were alive and dear to her.

Nau falls in love with a whale, Reu, and he transforms into a human to be with her. They become the parents of two whales, who eventually become people, and humankind is born. The story moves among Nau and Reu’s descendants, as they adapt to the changing world. Each generation behaves differently. Reu eventually dies, but Nau lives on. At first she is revered among her people as their grandmother, a living storyteller and memory keeper. But as the generations pass, her descendants begin to see her as a grumpy old woman. They scoff at her stories of Reu, and of the people’s kinship with whales, and their deep connection with the world around them and the creatures of earth and sea. They travel to distant shores, seeking riches and treasures and new experiences. They are more interested in hunting, and showing off their strength, then in listening to an old woman tell impossible stories about the way the world once was.

You can sense the fable here. It’s a creation myth, a story about climate change and ecological destruction, an elegy for a lost world, an urgent warning about what humanity stands to lose if we continue, as Nau’s descents do, to ignore her stories and her ancestral knowing. But unlike some fables, this book is also a tumultuous, emotional story about a remarkable woman who falls in love, raises a family, makes mistakes, longs for belonging, and struggles to make a place for herself in a world that is trying to forget her. Nau is so fully realized. She experiences great love and great loss, and those experiences translate to her interactions with others, her fears, what makes her laugh. She’s prickly and powerful and sad. She’s resourceful. She doesn’t let anyone else tell her how to be, even when they try. I was invested in her journey from the first page.

The other characters, too, are so real. The book hones in on a few of Nau’s descendants, and each one has a specific arc, specific challenges. They are not archetypes; they are people trying to do right by their families and communities, and often failing spectacularly. I was invested in their stories, too, even when I could see the destruction they were causing.

The lessons in the novel are wide and important: that we belong with the earth, and to cut ourselves from from the earth heralds our destruction. It’s a sad book. But it is also filled with glorious, musical language, and wild, irresistible joy. The descriptions of the Arctic landscape are stunning. The words pulse with wind and sky and ocean and rock. It is so physical, so deeply connected to the stuff of the world. It’s like the words themselves grew out of the ocean, a translation of whale song and sunlight on ice and summer wildflowers on the tundra.

There’s a wonderful translator’s note, in which Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse recounts a conversation she had with Rytkheu about her first translation of his work. She was worried, and wanted to make sure she was getting it right. He told her to “write it like a song. Like you could sing it if you wanted to.” When they met again after the book was published, he told her: “In English, too, it sings.”

This book sings more loudly and joyfully and precisely and wildly than most books I’ve read. It is gift I will cherish forever.

Frontlist: My Volcano by John Elizabeth Stintzi (Fiction)

Is it the weirdest book I've ever read? Maybe. Is it also tender, funny, and deeply moving? Yes. Stintzi has worked some truly incredible magic.

The book unfolds in a series of small sections, some only a paragraph, some a few pages. A volcano suddenly appears in Central Park. A white trans writer in NYC works on a sci-fi novel. A herder in Mongolia gets stung by a green bee. An eight-year old boy in Mexico City is transported to Tenochtitlan before the arrival of Cortez. A woman in Russia is engulfed by a giant insect, but no one seems to notice. There are mysterious lemons and buildings with animal legs and a purple light across Antartica. People show up in each other’s dreams. Mt. Fugi in Japan seems to have some mysterious connection to the volcano in Central Park, which comes to be known as Fugi II. None of it makes any sense.

Somehow, in all of these absurd happenings, and in the human concerns of the characters experiencing them, Stintzi captures the essence of what it feels like to be a human on this planet in the year 2022: the fear and exhaustion, the dazzling joys, the mysteries, the never-ending grief. The experience of reading this novel felt, to me, like being alive feels: swinging wildly from devastation to joy to hopelessness to anger to confusion to hilarity and back, over and over.

At one point, while looking at the volcano in Central Park, the white trans writer reflects:

It soothed them, soothed the despair at knowing there was no end to their struggles, there was no shape the jagged truths of their life could find to create some usable meaning.

And later, another character, an astronomer in Chile, is reading report after report of strange happenings all across the earth, and watching the people around him go on with their lives like nothing is happening.

He had spent so much of his short life moving from chair to chair, thinking about—searching for—unreachable worlds, but as these events progressed, he grew more and more convinced that this Earth was the same Earth that had always existed. That the current nonsense was, on paper, no less ordinary than the nonsense found in the whole of human history.

Much of the book feels like a conversation centering on these two ideas: that there is no way to explain the things that happen to us, that what is happening right now has been happening, in one way or another, for centuries. Nothing I make will ever mean anything, the white trans writer seems to be saying. And João, the astronomer, seems to be saying, these wonders, these atrocities, these happenings we cannot understand, are just a part of the bigger, mysterious, undefinable whole. It’s comforting and upsetting at the same time. Everything about this book is contradictory.

The book never stops. It's disorienting. Time does strange things. I was never quite sure of where I was, even as I came to know the characters and care deeply about their struggles. But despite the green swarm of networked beings that sweeps over most of Asia, and the character who discovers he's living in two places at once, and the dozens of other creative absurdities—this novel, at heart, feels bone-deep familiar, feels known, feels astonishingly true.

The novel is complicated even further by breaks between the chapters that depict real-life horrors, mostly police killings of Black people and the murders of trans women of color. These reminders of the violence happening all around us all the time act like lighting strikes. Stintzi doesn’t let us rest for very long in the imaginative absurdity of the world they’ve made—where volcanos appear suddenly and old women build reality out of nested dioramas. They’re always dragging us back to this place where we are. To the volcanos in our midst. Near the end of the novel, when things have escalated, there is this piercing line:

So many bodies on so many streets with so many different signs that all said roughly the same thing: we need to talk about what’s happening.

The world is incomprehensible. Every day brings new atrocities. We are destroying the planet, we are killing each other. We are cruel; we are tender. It's all happening so fast, and we can't stop watching, and all the while we go about our little lives, walking the streets and and eating dinner and calling our parents, and it's all so beautiful and impossible and strange, so dizzying and endless. How do we survive it?

I don't know. This book isn't an answer, but it is a witness to the wonder and the devastation. An acknowledgment, an elegy, an invitation, a spell. Brace yourself.

Upcoming: Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel (Speculative Fiction, Knopf, April 5th)

I generally prefer to write about under-the-radar books, rather than buzzy new releases, but sometimes I read a buzzy new release and love it, so here we are. I was a fan of Station Eleven, and this book has similar themes—it’s also about pandemics—but it is very gentle. This is the word I keep coming back to when I think about it. It’s a soft book. How do you write a soft book about a devastating pandemic, climatic destruction, a word irrevocably altered by the presence of humans? I don’t know. But Mandel has done it here. Though the book itself is sweeping, a modern epic that unfolds across centuries, Mandel focuses on the small stuff of our lives. The tiny details. The daily concerns. The almost imperceptible pleasures. The minutiae of family and work, falling in love, making art. This insistence—that even in catastrophe, our little hearts and their little concerns matter—gives the book a familiar intimacy. It’s sad, but the sadness doesn’t overwhelm. There were hints of this in Station Eleven, but it’s much more pronounced in this one. Maybe it’s because Mandel has now lived through a pandemic.

The story moves around a lot in time. A young Englishman arrives in British Columba in the early twentieth century. A woman in early 2020 New York (pre COVID) grieves an old friend. In the 2200s, a famous author from the moon colonies goes on a book tour on earth at the beginning of a pandemic. A few centuries later, another resident of the moon colonies takes a job with a mysterious government agency in an attempt to make something of his life.

I was riveted by all of these stories, but the most poignant for me was the pandemic book tour, and later descriptions of writing during lockdown. It’s clear that the writer, Olive Llewellyn, is a stand-in for Mandel, and while I dislike autofiction as a term, I love how Mandel writes herself into the narrative. I often found myself holding my breath, or having to pause the audiobook. It all felt so close, so eeriely accurate. It’s impossible to know how much of Mandel’s pandemic life she wrote into Olive Llewellyn, but the messy, imprecise blurring of our 2020-2022 reality with an imagined future reality got me right in the heart. I did not want to keep reading; I couldn’t look away.

This novel is also full of puzzles: how do all of these timelines intersect, and what does it all mean, and what do these charcters have to do with each other? And this is something else I love about it: Mandel plays no tricks. It all makes sense in the end. She doesn’t leave you hanging. There are no frustrating, unexplained mysteries. Sometimes I love a book that doesn’t explain itself (see above), but more often, I’m annoyed by it. Mandel doesn’t cheapen a complex story by tying it up in a neat bow, but she does tie it up. It’s so simple and elegant. Everything falls into place, but there’s some emotional ambiguity. Characters do not arrive neatly at their destinations. This is the sort of mess I love at the end of a book: I know how the pieces fit together, but the pieces don’t fit together neatly. They have jagged edges; they can still cut.

In addition to some version of Mandel herself, characters from her other works appear in this one. I haven’t read The Glass Hotel, characters from which apparently feature prominently in this. I didn’t feel like I was missing anything, but I do want to go back and read that one now. It makes sense to me, though, because at heart this is a novel about what it means to make art in an impossible time. It’s about all the tiny moments that preoccupy artists. We write novels about pandemics and wars, about future disasters and past atrocities. But in the end, most books are just about how we relate to each other. To me, this novel reads like an attempt to articulate that: a small, shimmering stillness in an endlessly swirling universe.

It’s out next week and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

Are you wondering what a savory bready pork thing is? This delicious baked delight is inspired by a recipe for lamb pide in the wonderful Soframiz cookbook. Pide is a flatbread popular in turkey, a yeasted dough filled with meat or veg and folded into a slipper shape. I made the dough as Soframiz instructed, but filled it with a mixture of pork, mushrooms, and caramelized onions, seasoned with oregano and tomato. So I don’t know if this is pide or not, but it sure is tasty.

Savory Pork Flatbread Roll

Ingredients

For the dough:

1/2 cup warm water

1 tsp active dry yeast

1 Tbs honey

180 grams (1 1/2 cups) all-purpose flour

3/4 tsp salt

2 Tbs olive oil

For the filling:

3 onions

A handful of mushrooms (~5-6; I used cremini, but go wild!)

5 garlic cloves, pressed

1 pound ground pork

2 Tbs tomato paste

1/4 tsp red pepper flakes

1 tsp oregano (fresh or dried)

1/2 cup grated cheese (Parmesan, Gruyére, or a combination)

2 Tbs melted butter (for brushing)

Make the dough: Combine the water, yeast, and honey in a large mixing bowl. Whisk briefly, and then let sit until foamy, about five minutes. Add the flour, salt, and 1 Tbs olive oil. Mix with a wooden spoon until a shaggy dough forms. Tip the dough onto the counter and knead until it becomes smooth and elastic, 5-8 minutes. Place in a lightly oiled bowl and let rise until doubled in size, about an hour.

While the dough rises, making the filling: Thinly slice the onions. Heat some olive in a large skillet. Sauté the onions over medium heat until they begin to soften, about 5 minutes. Turn the heat down to low and continue cooking, stirring frequently, until the onions are mostly caramelized, 15-20 minutes. Chop the mushrooms into small pieces, and add them to the pan along with the pressed garlic. Cook another 5 minutes, until the mushrooms have released some of their liquid. Add the ground pork, tomato paste, red pepper flakes, oregano, and salt. When the pork is cooked through, remove the pan from the heat and mix in the cheese. Let the mixture cool to room temperature.

Assemble the flatbread: Preheat the oven to 400 and line a baking tray with parchment paper. Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface. Roll it into a roughly 7x15 inch rectangle and transfer it to the baking sheet. Spoon the pork mixture down the middle, leaving two inches on each side and one inch on the ends. With the back of a spatula, press down on the pork to make an even layer. Fold the sides of the dough over the filling—don’t worry, the ends aren’t supposed to meet—and then pinch the ends to close. Brush with the remaining tablespoon of olive oil and bake until golden grown, 25-30 minutes.

Brush melted butter all over the flatbread as soon as it comes out of the oven. Serve warm.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Lamb Orzo with Roasted Carrots, Dates, & Feta

Friends! I made a very tasty dinner this past week! Cooking has been really hard lately, but this didn’t feel too overwhelming. I’m giving myself a pat on the back, and I’m sending what little cooking inspiration I have right now from my kitchen to yours.

First, quick pickle some red onions: thinly slice an onion or two and put them in a bowl with a few generous pieces of salt, a few generous pinches of sugar (or a spoonful of honey), and some red wine or sherry vinegar. Mix well and set aside.

Slice 3-4 carrots (on the diagonal if you’re feeling fancy.) Toss them with olive oil, salt, pepper, and a few drizzles of honey. Roast at 400 for about 15 minutes, until soft and nicely browned. Thinly slice about a pound of lamb (I had stew meat, so that’s what I used, but some other cut might work better). Heat some olive oil in a pan and add the lamb, along with a few pinches of Aleppo pepper, salt, pressed or minced garlic, and cumin seeds. Sauté on high heat until the lamb is just cooked. Remove the pan from the heat.

In a large bowl, combine the lamb (and all the tasty drippings from the pan!), carrots, a handful of chopped parsley, a big handful of slivered dates, a hefty amount of crumbled feta, and some cooked orzo. Mix well. Top with pickled onions and serve.

The Beat: Summer Sons by Lee Mandelo, read by Will Damron

I’ve listened to a string of audiobooks recently that haven’t wowed me, and I’m hoping this will be the book to break the streak. It’s still too soon to tell, but I’m into it! It’s very eerie and dark. The main character, Andrew, has just arrived at Vanderbilt to try to figure out what happened to his best friend, who died suddenly, apparently by suicide. Right now all I want to read is character-driven, emotional queer lit, and so far this is exactly that. I also really like the narrator, Will Damron (he was fantastic in Let’s Get Back to the Party and also did a great job with Bad Blood).

The Bookshelf

The Visual

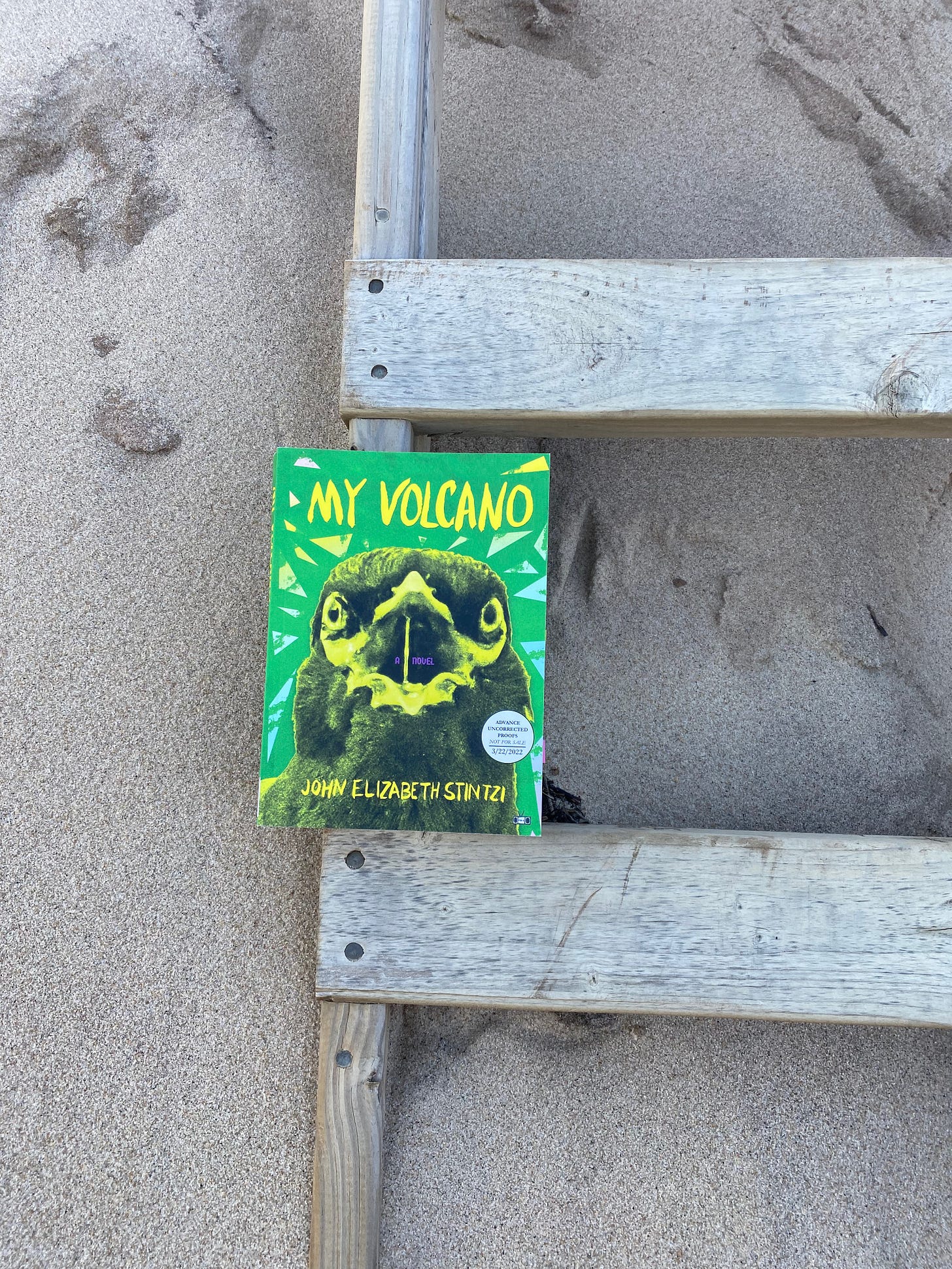

I took a bunch of books to the beach the other day to do a photoshoot, something I rarely do. It was fun! Here’s a picture I took of My Volcano on a ladder in the sand. I’m not sure why, but something about the setting seemed appropriate.

Bonus Recs with a Wisp of Magic

Look Who’s Morphing by Tom Cho and Sea, Swallow Me by Craig Laurance Gidney: two strange, wonderful, just-a-little-bit-magic (or maybe not) short story collections. Ruth Ozeki excels at this kind of writing, too. A Tale for the Time Being is my favorite, but I also loved her newest, The Book of Form and Emptiness. Watch Over Me by Nina LaCour is a beautifully quiet YA story with the kind of magic you hardly notice until you can’t look away.

The Boost

Roxane Gay: “Jada Pinkett Smith Shouldn’t Have to ‘Take a Joke.’ Neither Should You.” (Via NYT)

Ijeoma Oluo: “We Have the Right to Not Be Annoyed” (Via her fantastic newsletter)

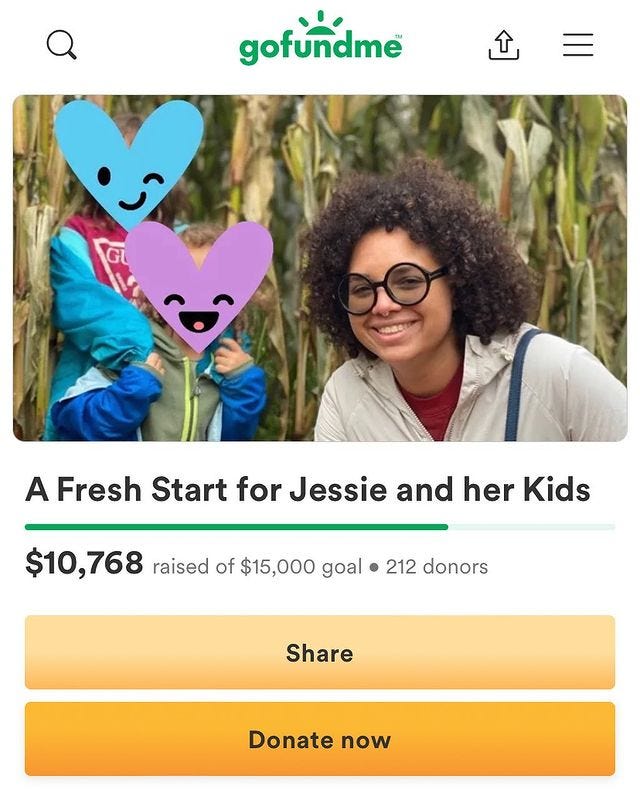

Jessie is a shining light in the Bookstagram community in which I dabble. I turn to her reviews again and again (I just reread her thoughts on The Cancer Journals after finishing it last weekend). Right now she’s in need of financial support for ongoing exepenses related to her divorce and upcoming trial. You can donate here.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: The ocean, once more, for the road.

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

I just picked up My Volcano and am excited to read it based on your review. I’ve never been disappointed in a book from Two Dollar Radio. Thanks!