Greetings, bookish friends! I’m on vacation this week, which means I wrote this newsletter last week and proofread and scheduled it last night. This morning I woke up to news about the shooting at an elementary school in Texas. In bed, I scroll through words and words and words and words and I don’t have any more words. We are destroying ourselves. It is not bearable.

Here’s the newsletter.

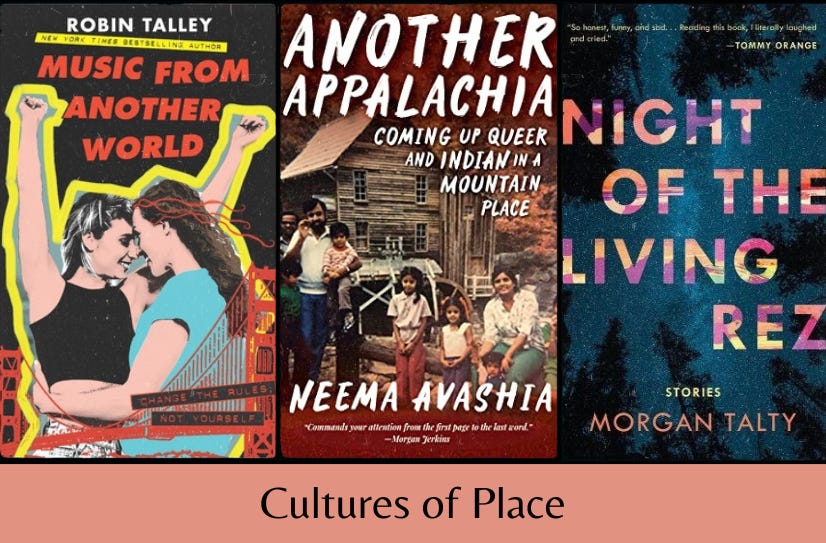

There is little I love more than books about place and home. I’ve written newsletters on these themes before: coming home, queer city life, and landscape as character. This week’s books are about cultures steeped in place. They explore how places shape culture, how culture shapes places, how landscape and culture and identity intersect. There’s a novel set in San Francisco, a memoir set in West Virginia, and a collection of short stories set in Maine. Each of these books is singular and specific: they could not take place anywhere other than where they’re set.

The Books

Backlist: Music from Another World by Robin Talley (YA Historical Fiction, 2020)

I gobbled up this YA novel about two queer teenagers coming of age in 1970s California. Tammy lives with her religious family in Orange County—she goes to a Christian high school and attends a conservative church. At home, her aunt is constantly spouting homophobic rhetoric and volunteering for various anti-gay political campaigns.

In San Francisco, Sharon lives with her mom and older brother. She goes to a Catholic high school, and she’s helping her brother keep the fact that he’s gay a secret from their mom. She is steeped in some of the same religious hate and homophobia that Tammy is, but she has access to San Francisco, and it’s here that she begins to find herself and her voice, through the punk music scene and the gay rights movement.

Tammy and Sharon are assigned to each other as penpals for a school project. The write dozens and dozens of letters over the course of the summer, slowly revealing more and more of who they are to each other. Finally, Tammy arrives in San Francisco, desperate to meet Sharon in person and get away from her stifling family. They become friends, and eventually fall in love, although the heart of the book is their friendship—it’s about the courage and sense of home they each find in the other.

This novel is all about place, and how the culture of a place intersects with identity, especially in young people trying to figure out who they are. Tammy knows she’s a lesbian, but she doesn’t have anywhere safe to talk about it, except in her journal, in which she writes letters to Harvey Milk. The religious culture of the community in which she lives influences how she sees herself and the world. The only way she knows how to truly be herself is to leave the place that helped shaped her.

Sharon’s understanding of herself is complicated by the fact that she does have access to queer culture, first through her brother, and then through the punk music scene. But she also goes to Catholic school, where she’s constantly bombarded with the message that homosexuality is wrong. Her journey to owning and celebrating her bisexual identity is an internal one, but it’s marked by moving out of one culture of place and into another, freer one.

I love everything about this book. I love how deeply steeped it is in queer community. It’s set against the backdrop of gay activism in the 1970s in San Francisco, and it’s such a poignant exploration of how life-changing movements can be for young people. I love how much Tammy and Sharon grow over the course of the book, and how that growth isn’t just because of their friendship, or their eventual romance, but because they both venture out into the world, to find their people, to find the places that will hold and challenge and inspire them.

Sharon finds community in the punk music scene. There’s a queer feminist bookshop in San Francisco that becomes important to both her and Tammy. Near the end of the book, Tammy returns to Orange County as part of a protest against Anita Bryant and Prop 6. All of these moments brought me back to my own (very different) teenage years—the guidance office where my GSA met that felt like home, the first time I took the T into Boston with friends for a protest, the used bookstore I used to browse for hours. The physical places we have access to impact our lives in lasting and sometimes unexpected ways.

This novel is told through letters and journal entires, and while the journal entires felt a bit unrealistic at times, I didn’t care, because I was so invested in Tammy and Sharon. It’s such a complicated portrayal of self-discovery, friendship, and finding your people.

Frontlist: Another Appalachia by Neema Avashia (Memoir)

I bought this one a whim—I think it was my fellow Rioter Kendra Winchester (who has a fantastic newsletter about disability, Appalachian life and lit, and her unbearably cute corgis, among other things) who put it on my radar. I ended up reading it in one day!

It’s a short book (165 pages), but Avashia packs a ton into it. It’s a memoir about being queer and Indian and Appalachian, but it’s also about teaching in public schools, Western standards of beauty and womanhood, her relationship to Hinduism, neighbors and neighborhoods, the history of the chemical industry in West Virginia, the intersection of Indian and Appalachian food, grief, partnership, the complexities of writing nonfiction about family, shame, immigration, Boston.

In the essay ‘Chemical Bonds’, she describes the small West Virginia town where she grew up. Her immigrant parents settled there in the 1970s after her father took a job as a doctor for the Union Carbide plant, one of the massive chemical corporations that provided jobs to thousands of West Virginians in the region known as the Chemical Valley. She writes about her father’s role in the community, and what she learned from him about what it means to be in community:

My father’s ethics were not typical, and certainly might have been frowned on by the medical establishment, but at the time, I understood them as the ethics of place: Being a good neighbor, and by extension a good person, meant giving 100 percent of what you had to the community where you lived. The “rules” mattered less than the impact of your actions.

At the end of the same essay, she comes back around to this idea of being a good neighbor and what it means: “I once viewed my father’s ethics as the ethics of community. Now I wondered if in fact they had been the ethics of assimilation, or the ethics of survival.”

The book is full of contradictions like this. In another essay, she contemplates her relationship with Mrs. and Mr. B, an older white couple from her hometown, her adopted grandparents. These are people she loves deeply, whom she still returns to visit even after her parents have moved from West Virginia to Texas. After Mrs. B dies, Mr. B begins posting racist, pro-Trump rants on Facebook. Avashia doesn’t defend him; she writes about how upset and uncomfortable and heartbroken it makes her, as if she’s never been seen by people she loves. But she also speaks to the fact that she can’t simply turn off her connection to him, as much as a part of her wants to.

There are so many layers to relationship, to culture, to the places we love and call home. So many layers in leaving a place, in returning, in returning changed and leaving again. Avashia delves into all these layers. She writes with such startling love for her West Virginia hometown, for the Indian aunties and neighborhood parents who defined the place for her. She writes about specific people from this place she has loved, the colors of her mother’s garden, the meals she ate with friends, the sense of deep belonging she felt among them. She also writes about the racism she faced in school, in town, everywhere. She writes about how, growing up Hindu in a white, Christian town, she was made to feel again and again like she didn’t belong in the place where she was born.

Am I from here, or am I not? It depends on who you talk to, and when you talk to them.

It depends on what has happened to me in the moments before you ask the question.

As an adult, Avashia has made her life in Boston, as a teacher in the Boston Public Schools. She writes about her life in Boston—her dedication to her work, the house she shares with her wife—with a love and intensity that is different from how she writes about Appalachia, but no less real. Her feelings about her adopted home are complicated, too. She has been deeply shaped by all the layers of place that live inside her—her parents’ home country, India; the West Virginia hills; Boston. All of these places come alive in the book. It’s a gorgeous meditation on wholeness and longing and what it means to live both grounded and in-between.

I do not know what it means to possess a love of place so strong you remain rootbound even when the soil sometimes rejects your very existence. My wandering parents, living in their fifth home, fourth state, and second country, certainly do not. I want it. I hunger for it. Sometimes, I even trick myself into thinking I have it. But a dinnertime conversation with a woman whose family has been buried in the same cemetery for five generations quickly reminds me that I do not. And in the moment of self-pity that follows, I consider the fact that while the hills of West Virginia shapes me into the person I am today, I have passed beyond them, my shallow roots trialing behind me as I go.

This book reminded me a lot of Brown White Black by Nishta J. Mehra. There are the obvious similarities—both are memoirs by queer Indian American women who grew up in the South—but on a deeper level, they both engage openly with contradiction. Both Avashia and Mehra write about the complications they hold inside themselves, the messy intersections of place, culture, and family. They circle back around to ideas and experiences from new vantage points. They do not offer any certainties, only questions. I read Brown White Black years ago but reading this book made me want to return to it.

Upcoming: Night of the Living Rez by Morgan Talty (Short Fiction, Tin House, July 5th)

This collection of linked stories is set on a Penobscot reservation in Maine. They are all narrated in the first person by the same character, David, but they move back and forth in time. In about half the stories, David is a child and then a teenager. In the other half, he’s in his twenties. The stories alternate between these two time periods, so that instead of watching David grow up chronologically, we witness a series of important moments in his life.

I’ve become much more excited about story collections in recent years, but it’s still rare that I love a book of stories as much as a novel. This book isn’t a novel, but it has the heft of one. The structure is breathtaking. It’s not because the stories are focused on one character and his intimate relationships. It’s because of the way Talty builds the book, each story changing what came before it. We see David in so many different situations—getting high with his best friend Fellis, attending a ceremony, in town at the methadone clinic, in his room listening to his mother and her boyfriend argue. We see him as a kid playing in the woods, and as an adult walking through the same woods. We see him visiting his grandmother at her nursing home, listening to her stories, and on the phone with his distant dad. Driving around the dark reservation roads in winter. In so many kitchens.

Talty captures each of these ordinary moments in stories that stand on their own. But they also work together. Each new story illuminates something new about David’s life, his family, his community, the reservation. Events come up again and again, and David’s memory of them shifts. As I got deeper into the book, I started to realize that Talty was taking me somewhere, that there was something lurking in the center of the story that I couldn’t see directly, a presence that became more and more persistent. I gasped when David finally comes around to look at it directly in the final story.

Talty’s prose is easy, certain, direct. It’s the sort of writing that disappears into the story. It’s elegant in a way that draws your attention to everything happening underneath the story, the emotions fueling actions. The Maine landscape is ever-present. There is a lot of snow, trees, water, weather. It’s not a particularly descriptive book—not overly descriptive. It’s just that the place is present in every sentence. There is no book without the reservation where it’s set. Its beauty and history, brutality, closeness. The wind and the bridge to town, the roads, the woods, the houses, the icy river. These are not colorful details but the beating heart of David’s life. The place—and the role it plays in the lives of the people who live there—is what the book is about.

David often muses on this interconnectedness, the sense that he’s one strand in an interconnected web of land and people, despair and pride, past and present:

When we were almost home, riding over the bridge to the Island, I sensed that even though their problems were their own, there was no escaping how those problems shaped us all, no escaping the end, like the way the ice melts in the river each spring, overflowing and creeping up the grassy banks and over lawns, reaching farther and farther toward the houses until finally the water touched stone, a gentleness before the river converged on the foundation, seeping inside and flooding basements, insulation swelling, drying only when the water has receded.

This is a book full of pain. It deals with sexual assault and opioid addiction, violence toward Indigenous people, grief, inherited trauma. But it’s not a book about pain. It’s a book the messy lives of David and his family, neighbors, community. It’s about betrayal and mistakes, loneliness, the feeling of being stuck. It’s about friendship and laughter and unconditional love and the weight of stories passed down through generations. It’s about what it means to love the place that made you, that holds you and hurts you, that kicks you out and calls you back.

It’s out on July 5th, and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

I am usually in bed by 8:30, but the other day around 9pm, after another week of grief and rage at the world, I knew I wouldn’t be able to sleep unless I calmed myself down. So I pulled out the stand mixer, the jars of flour and brown sugar, the chocolate. Cookies are the ultimate comfort bake for me. They are so familiar.

This recipe is very lightly adapted from Flavors of the Sun by Christine Sahadi Whelan. I’m always eager to try new variations of chocolate/halvah/tahini/sesame cookies because it’s my favorite favorite combination.

Comfort Cookies

Makes 24-30 cookies

There is a lot of halvah in these—more than I’d usually put in a cookie. It’s the dominant flavor, and it makes the cookies very chewy and sesame-full. They are also quite sweet. I’d usually say just leave it out if you don’t like it or don’t have it, but the volume is so high, I’m not sure what removing it would do to the overall mix. If you experiment with reducing the amount or leaving it out, let me know how it goes!

Ingredients

1 1/2 sticks (165 grams) unsalted butter

280 grams (2 cups) all-purpose flour

1/2 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp salt

200 grams (1 cup) brown sugar (I used dark brown sugar, which makes the cookies very caramely, but any kind will do)

100 grams (1/2 cup) white sugar

2 eggs

2 tsp vanilla

180 grams (about 1 cup) bittersweet chocolate, chopped

450 grams (2 cups!) halvah, crumbled or broken into small pieces

flaky salt and sesame seeds for sprinkling (optional)

Preheat the oven to 325. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper or silicone baking mats.

In a small saucepan, melt the butter over medium-low heat. Keep cooking, swirling the pan from time to time, until it turns golden brown, about 6-10 minutes. Remove it from the heat when it begins to smell nutty, and the bubbles in the pan have quieted. Pour it into a shallow bowl and stick it in the fridge (or freezer) to cool down to room temperature.

Combine the flour, baking soda, and salt in a small bowl and set aside. In the bowl of stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, or with electric beaters, combine the cooled butter, both sugars, the eggs, and the vanilla. Add the flour and beat on low speed until just combined.

Add the chopped chocolate and all but 1/4 cup of the halvah. Mix for a few seconds on low speed, and finish mixing by hand to ensure the chocolate and halvah are evenly distributed.

Roll small balls of dough between your palms (it will be very soft), about 1 1/2 tablespoons each. Place on the prepared trays about 1 1/2 inches apart (they do spread a bit). Press a bit of the reserved halvah into the top of each cookie, and sprinkle with flaky salt and sesame seeds. Bake for 12-14 minutes, until just set. Repeat with remaining dough (if you have any).

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Easiest Egg Salad

When I ran a farm, I used to make egg salad for farm lunch in the spring all the time. These days I rarely think to make it, and I don’t know why because it is delicious and easy and such a great way to use lots of spring greens and early veggies!

Hard boil some eggs. I usually do 10-12, so I can make a big batch and keep it in the fridge for lunches throughout the week. Next, chop a bunch of stuff: lots of dill, scallions and/or chives, a cucumber if you have one. Red peppers are nice, as is celery. I also love radishes in egg salad, or chopped pickles. I added capers to this batch. Sometimes I use basil in addition to the dill. Mash up the eggs in a bowl, add the veg and herbs, and mix well. I hate mayo so I make a dressing with a few tablespoons of yogurt, a tablespoon of mustard, a glug of olive oil, and a splash of sherry vinegar. Add salt and lots of pepper, pour over the egg salad, and toss to coat.

The Beat: The Impossible City written and read by Karen Cheung

One of my favorite kinds of books right now are books set far away from where I live. I like the reminder that the world is vast and my life is small. There’s something comforting about it. I just started this one and I love it so far. The beginning is a meandering introduction to Hong Kong and Cheung’s life there, but I’m already impressed with the way she writes about the city—as a living thing, both concrete and amorphous. She writes about all the parallel cities that exist within Hong Kong—there was a particular passage that struck me about being able to live your whole life in a city without seeing or experiencing some versions of it.

The Bookshelf

A Picture

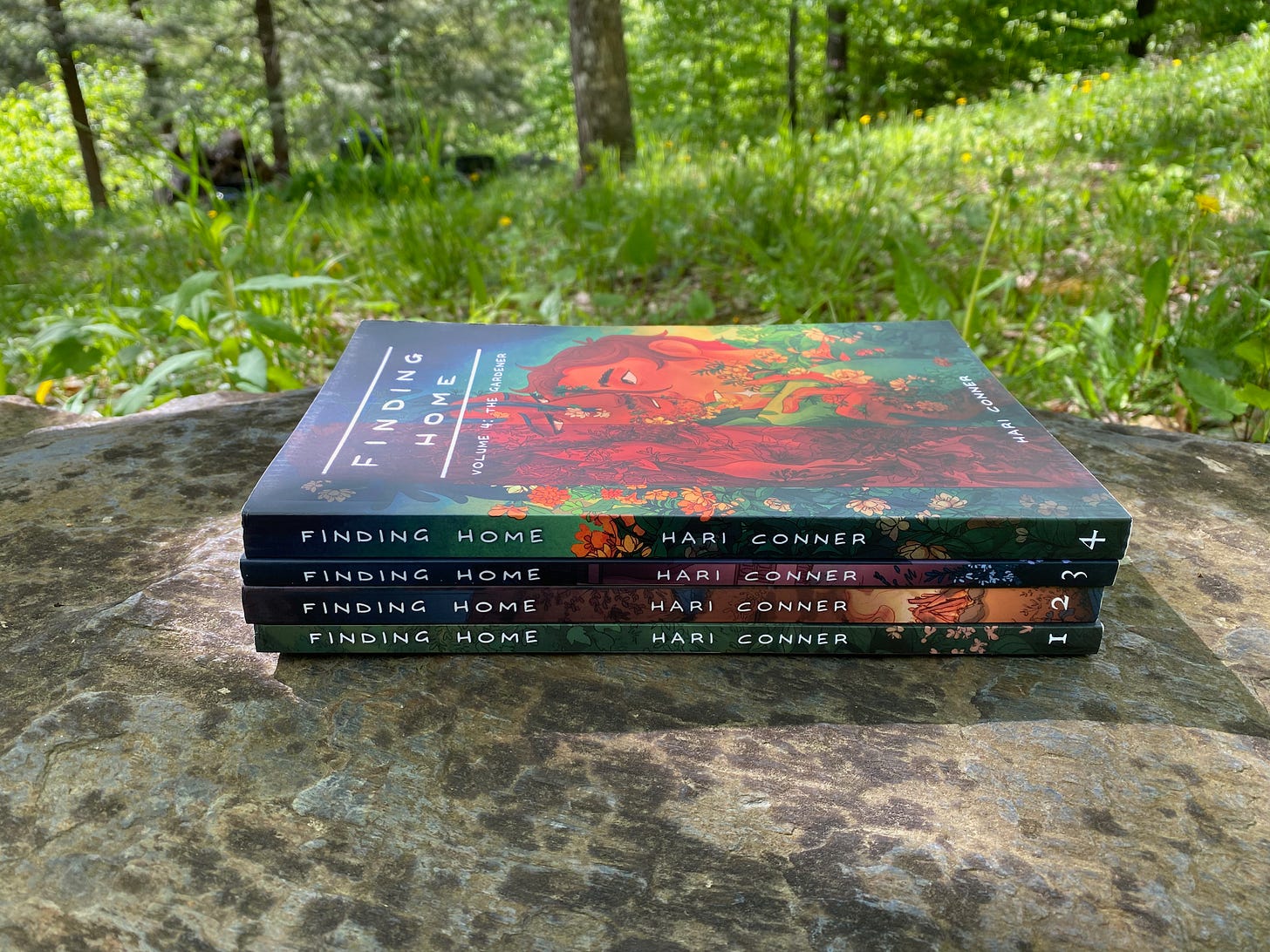

I know I’ve mentioned how much I love Finding Home by Hari Conner in previous newsletters. The fourth and final volume of this incredible comic arrived in the mail last week, and I spent the first day of my vacation rereading the whole series. It is one of my favorite comics of all time. If you love queer romance and beauty and magic and wildness, if you're longing for a story that will remind you that we can be gentle with each other, we can slow down, we can let ourselves become momentarily overwhelmed by wonderment, we can show all of our soft, messy insides to others and be seen, celebrated, known—this is your book. You can read it free on tapas, but if you want to get the whole story now, you can become a patron of Hari Draws on Patreon.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I wrote about my love for translator’s notes, and how they change the way I read books in translation. I also wrote about the joys of being a queer reader in the Golden Age of Queer Lit, and how, every now and then, I choose to read books about straight people.

Now Out

Hurray! You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi is now out! I reviewed this romance at the end of last year, and surprise, I absolutely loved it.

Bonus Recs Featuring Cultures of Place

It is likely that I was subconsciously thinking about the subtitle of Belonging: A Culture of Place by bell hooks when I came up with the name for this week’s theme. It’s my favorite of her books (that I’ve read). How Much of These Hills is Gold by C. Pam Zhang is a beautiful historical novel set in the post-Gold Rush West. It’s about the beauty and violence of place, and the intersections of race, geography, gender, and queerness.

The Boost

One of the organizations that receives a monthly donation from me: Black and Pink Massachusetts, a prison abolition organization that supports incarcerated and formerly incarcerated LGBTQ+ people.

A useful thread about writing alt text/image descriptions.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I am in love with this birch tree in my yard.

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

Loved your piece on Book Riot about the absolutely mind-boggling wealth of queer literature we get to enjoy now and how much it would have rocked to have access to similar as a younger person. Also, though it may not be notably queer in content, the Vanishing Fleece's author Clara Parkes is indeed gay. :)

Do glad you enjoyed Neema Avashia’s book! Her writing is fantastic. 🤩