Greetings, book-eaters and treat lovers!

I have a goal for May: to spend thirty minutes every day doing something creative, generative, and/or new. I love being home more than being just about anywhere else—but I need a change of scenery, a new project, a reset. I want to be making and creating, not just looking and reacting. So I’m focusing on creation this month.

On Monday I spent some time looking through these amazing plant lists put out by the Massachusetts Pollinator Network, and made a list of perennials I want to plant this year. On Tuesday I did some digging in my garden beds! And I’m planning to make these garlic chive dumplings later this week.

As far as books go, regular themed newsletters are finally back! I’ve been struggling all week to come up with a good name for today’s theme. It’s just not that these books tackle difficult subjects, although some of them do. It’s more that they’re willing to look at the world as it is, in all its contradiction and complexity. They dig into lots of messy knots and don’t try to untangle them. They’re the book equivalent of hard conversations: maybe we don’t want to have them, but if we don’t, we’ll never learn or change or grow.

The Books

Backlist: We Will Not Cancel Us by adrienne maree brown (Nonfiction, 2020)

I have to start by saying that while I loved this book, learned a lot from it, and deeply appreciate brown’s vulnerability and insight, it feels kind of terrible to be writing about it this week. I suspect it would feel this way if I wrote about it next week, or the week after, or next month. There is always something unbearable happening in this country (and the world), and while I believe this book has immense value, it is mostly a book about language and intra-movement dynamics. It’s about how we do activism. And right now, after the white supremacist murders in Buffalo last weekend, and with the far right mobilizing so effectively to ban abortion, health care for trans people, and books that discuss racism, a book like this doesn’t feel like enough. I don’t mean to imply that what brown writes about doesn’t affect real lives, or that her ideas have no practical application. That’s not true, either. It’s just: a lot of things feel small right now. Books like this. Abortion rallies. Voting. We need all of these things, certainly. But it’s never enough. It’s exhausting and terrifying.

So. I’m going to talk about the book now. It’s not a critique of cancel culture or call-outs in general. Call-outs are a powerful tool, especially when the people doing the calling out are not in positions of power, and those who have harmed and abused them are. This is not a book about powerful white people who have been “canceled”. If you know anything about brown’s work you probably already knew that. I just want to be as clear about it as brown is.

This book is about what happens to radical movements when call-outs become the default mode for addressing all forms of conflict and disagreement. It’s about what happens when call-outs are used indiscriminately, not only in cases of abuse and harm, but as a way to address critique, contradiction, misunderstanding, and mistakes. She teases apart these various concepts, arguing that while call-outs in cases of harm and abuse are often vital and necessary—as when survivors come forward—call-outs as a response to critique and conflict often set off new cycles of misunderstanding, and leave no room for true healing, accountability, and growth.

In my vision of healthy movements, we are able to easily communicate about whether we are in a conflict or misunderstanding, if we are uncomfortable with how others are navigating contradictions, if we have or are receiving a critique, whether harm has happened or is happening, and whether we are witnessing or experience abuse.

It’s not cancel culture that’s the problem; it’s the lack of nuance in how we respond to everything that’s bad—because everything isn’t the same kind of bad. brown is interested in real transformation, in building strong, complex movements that can enact lasting change. If we do not allow for growth within our own communities and movements; if we cannot create space for learning and deep listening; if we refuse to engage in conflict that is generative; if we hold every person we encounter, in the world and on the internet, to standards of absolute perfection—then we’re going to be here in the muck together forever, caught in the same cycles, never moving forward.

There’s a lot learn and ponder in this short book. A part of it was originally published as a blog post, and brown devotes considerable space to responding to the critiques of the original post, and explaining how those critiques lead to the book in its current form. She enacts the process she writes about it. This, for me, is the biggest takeaway: that we must model the kind of world we want to live in.

Movements need to become the practice ground for what we are healing towards, co-creating. Movements are responsible for embodying what we are inviting our people into. We need the people within our movements, all socialized into and by unjust systems, to be on liberation paths. Not already free, but practicing freedom every day. Not already beyond harm, but accountable for doing our individual and internal work to end harm and engage in generative conflict, which includes actively working to gain awareness of the way we can and have harmed each other, where we have significant political differences, and where we can end cycles of harm and unprincipled struggle in ourselves and our communities.

brown’s vision is compelling. I don’t know how we’ll get there, but I do know that we don’t have any hope of getting there if we don’t make space for the hard mess of trying to create a better world in the midst of one we’re living in.

I have a vision of movement as sanctuary. Not a tiny perfectionist utopia behind miles of barbed wire and walls and fences and tests and judgements and righteousness, but a vast sanctuary where our experiences, as humans who have experienced and caused harm, are met with centered, grounded invitations to grow.

Frontlist: Flung Out of Space by Grace Ellis and Hannah Templer (Graphic Fiction/Biography)

In the introduction to this fictionalized biography of Patrica Highsmith, author of The Price of Salt, Grace Ellis writes about what a terrible human she was. She was mean and argumentative and vindictive and deeply unhappy. None of these traits are necessarily character flaws, of course, especially in a queer woman in the 1940s and 1950s trying to make a name for herself as a writer. But Highsmith was also racist and antisemitic. She treated people terribly, including the women she slept with. Ellis does a great job contextualizing Highsmith and her legacy—she makes it clear that, in telling the story of Highsmith’s life, she is not condoning her beliefs or actions. She ends the introduction by explaining that if you feel conflicted and a little sick about Highsmith and her work after reading this book—good.

This story focuses primarily on how she came to write The Price of Salt. She’s living in New York, writing low-brow comics (which she hates, judges, and doesn’t want her name attached to). She’s trying to sell the book that will become her first big success, Strangers on a Train, but no one is biting. She’s depressed. She feels trapped and misunderstood and alone. She’s in and out of conversion therapy. She has a series of affairs that seem desperate and frenzied—she sleeps with women but doesn’t show herself to them. She doesn’t show herself to anyone. It’s one of these affairs, combined with a random encounter in a department store, that ignites the story that becomes The Price of Salt.

It’s interesting that she has become known for this classic of lesbian literature, the first such book with a happy ending, given that she herself was so unhappy. It’s heartbreaking to read the story behind the story, to see the flawed and striving artist who created it. It makes The Price of Salt feel like a fantasy—as if Highsmith wrote the kind of story she knew she’d never have, but longed for.

I loved learning the history behind a book that has been so impactful for so many queer women. I especially love that Ellis and Templer do not cast Highsmith as a romantic hero. They don’t make any attempt to turn her into a sympathetic character. They don’t make her out as a villain, either—she’s a human, entangled in human messes—but they make no excuses for her.

The book isn’t directly about her racism and antisemitism, but both come up, often in casual conversation or mundane interactions with strangers. Highsmith was charismatic when she wanted to be. So there’s a scene showing her in her apartment, writing, aware of her own talent and clearly exhausted and angered and broken by a world that treats women as less than, incapable, invisible. Then there’s a scene of her seducing a woman in a bar, all smooth charm. Then there’s a scene of her walking down the street, muttering antisemitic comments to herself. It’s jarring and upsetting and a little dizzying to read. It’s a whole picture of a terrible person whose writing, is, undeniably, a vital part of the queer canon.

This tension is at the heart of what I mean by talking about the bad stuff. There’s a big difference between talking about something and celebrating it. This book is not a celebration of Highsmith. It’s not possible to separate the artist from the art, but it is possible to speak truthfully about artists and their art. This, I think, is where we start. The Price of Salt is celebrated because it was so radical for its time, when publishers basically required a tragic ending in order to publish a lesbian novel. So is the fact of it worth celebrating? Should we even bother to talk about Highsmith? Should we cast out The Price of Salt altogether? I don’t know. I don’t think so. Ignoring something is usually more harmful than facing it. The one thing I’m sure of is that praising the book without reckoning with the woman who wrote it isn’t going to get us anywhere.

Upcoming: Rainbow Rainbow by Lydia Conklin (Short Fiction, Catapult, May 31)

These stories are messy and complicated and often dark. They are about generational differences between queer and trans people, growing up in the suburbs, friendship, the challenges of intimacy. They are full of queer and trans characters uncovering and excavating themselves, and sometimes hiding themselves, too. A queer couple is trying to conceive a baby and it shakes up their whole relationship. Two people navigate the wonder and pain and logistical challenges of a pandemic hookup. A trans kid comes to understand something about their identity during a reenactment of the Oregon Trail at their elementary school. A middle-aged trans person attends a conference with their internet-famous trans nephew and struggles to find the courage to come out to him. Teenagers fall in love and have disastrous crushes and get drunk and pine for their friends and are cruel to each other. They are lonely and impulsive and righteous and lost.

There’s a lot of sex in these stories and a lot of it is uncomfortable and sometimes upsetting. There is sexual violence and sexual abuse of teenagers. I did not find any of it gratuitous, though these things are always difficult to read about. This is a book to approach with care. I’ve been thinking, since I finished it, why it felt so dark, why I found myself often wanting to turn away from it even as I was completely invested in the characters. Sexual violence is sexual violence. Full stop. But there are also stories in this book about kids and teenagers exploring their bodies and their desires, trying to learn about the world and themselves without the support of adults who care about them. There are a lot of teenagers who are alone, isolated, unsafe. Queer and trans teenagers without any adult role models. Queer and trans teenagers unseen by their peers. Some of them make really bad choices. Some of them seek approval and attention from adults who turn out to be predatory.

Most of these stories are written from the POVs of the teenagers living through these things—characters who are in pain and confused and yearning for something they don’t know how to name. The narrators aren’t adults, looking back at their adolescence from a safe distance, with the ability to provide context, relief, understanding. It is all very immediate and very dangerous. I did not want these queer and trans babies to be in the situations they were in. But there are teenagers—far too many—who are in these situations.

There are also plenty of stories about adults, and adults also wrestle with how to live in the world: how to love, how not to lose themselves, how to forgive, how to own up to their mistakes. This book does not have “good” representation. It’s not a book about good characters who do the right thing. It’s not about people who are easy and likable. We are starting to get more and more books like this that portray queer people as flawed and fallible and all I have to say is: more please!

As an added bonus for me, many of these stories are set in my hometown (and I’m pretty sure Conklin went to my high school but it was a big high school and I was a hermit so who knows). Anyway, it’s always a treat to read books about places you know well. One of the stories is set at the elementary school my cousins went to. Several others mention neighborhoods where friends of mine lived. Everything about the way Conklin describes the Boston suburbs is exactly right. Taking the bus to the T to get into the city. The exhilaration of actually being in the city, especially as a queer teenager used to your boring little town. Getting and giving rides—so many rides! Rides were such a big part of my teenage years in the suburbs. There are rides all over these stories and it brought me right back. It all felt especially intimate to me because I recognized street names, school names, bus routes, highways. But you don’t have to be from my town to relate to the way Conklin writes about growing up queer in suburbia.

It’s out on May 31st and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

This bake…is not a bake. But you can easily turn it into one! I made a very simple lemon cake from, you guessed it, my new fav, Snacking Cakes, and sandwiched it with rhubarb and custard. You could make these delicious lemon cupcakes, and fill them with rhubarb and custard instead of lemon curd. Or make a simple, elegant rhubarb & custard tart (here’s a simple pie crust recipe). But if it’s too hot and you don’t want to bother with any of that, you can’t go wrong with a bowl of luscious vanilla custard and tart rhubarb compote—especially with sliced strawberries and whipped cream on top.

Rhubarb & Custard

This recipe makes about two cups of custard and 1 1/2 cups of compote. In other words: one night of dessert for your friends and fam, or a week of dessert for just you. The custard (i.e. creme patisserie) is from Dorie Greenspan’s newest book, Baking with Dorie.

Ingredients

For the custard:

2 cups (480 ml) milk

6 egg yolks

100 grams (1/2 cup) sugar

43 grams (1/3 cup) cornstarch

1 Tbs vanilla extract

50 grams (3 1/2 Tbs) unsalted butter, softened

For the rhubarb compote:

6 medium stalks rhubarb (about 520 grams) chopped

205 grams (2/3 cup) honey

For the custard: In a medium bowl, whisk together the eggs, sugar, and cornstarch until well blended.

Heat the milk over medium heat until warm but not boiling—remove it from the heat when you see small bubbles forming around the edges of the pan.

Whisking constantly, slowly pour a little bit of the warm milk into the egg mixture to gently warm the eggs. Continue pouring the rest of the milk into the egg mixture, whisking the whole time.

Return the mixture to the saucepan and bring to a boil, still whisking constantly. Once it’s boiling, the custard will thicken quickly—it only takes 1-2 minutes. Remove it from the heat as soon as it thickens. I promise you’ll be able to tell.

Pour the custard through a fine mesh strainer into a clean bowl. Add the vanilla. Let cool slightly, about 8 minutes, and then add butter in small pieces. Press a piece of plastic wrap directly on top of the custard and put it in the fridge for 1-2 hours to chill before using.

For the compote: Combine the rhubarb and honey in a medium saucepan over medium-low heat. Stir constantly to evenly distribute and dissolve the honey, then turn the heat up to medium and bring to a simmer. Let cook, stirring occasionally, until the rhubarb softens and falls apart and the mixture thickens and reduces, about 20 minutes. If you want you can give it a quick blend with an immersion blender.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Herby Rice Salad

It was too hot to cook over the weekend. Happily I had some leftover cooked rice, which I turned into this delightful and refreshing spring salad.

Chop up a bunch of fresh herbs, whatever you have. I used dill, basil, and garlic chives. Chop a few scallions. Thinly slice a fennel bulb and handful of dates. If you have one, chop up a cucumber. Toss it all in a big bowl with some toasted slivered almonds, golden raisins, and crumbled feta. Add some leftover cooked rice and mix well. If you have pickled shallots or onions lying around, they’re great in this. If not, make some: thinly slice an onion and toss it in a bowl with some red wine vinegar, a pinch of salt, and a pinch of sugar. Let sit for 10-15 minutes, then add the quick pickles and their juices to the bowl. Make a dressing with olive oil, sherry vinegar, a spoonful of mustard, a pressed garlic clove, salt, and pepper. Toss to coat.

The Beat: When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill, read by Kimberly Farr and Mark Bramhall

I was hesitant to pick this up, thanks to my ongoing can’t-handle-fantasy brain, but I’m so glad I did because I can’t put it down. It’s a historical novel with a little bit of magic, namely that one day in 1955, hundreds of thousands of women spontaneously transform into dragons. Alex is a kid in Wisconsin when it happens, and her aunt is one of the women who transforms. Her cousin Beatrice comes to live with her family, and it’s like her aunt never existed. Beatrice is her sister now; she never had a mother. Interspersed with Alex’s first person narration are bits and pieces of ephemera that illuminate not only the Mass Dragoning of 1955, but instances of dragoning throughout history. I’m not that far into it but I am inhaling it. It’s very queer and full of rage and so creative.

The Bookshelf

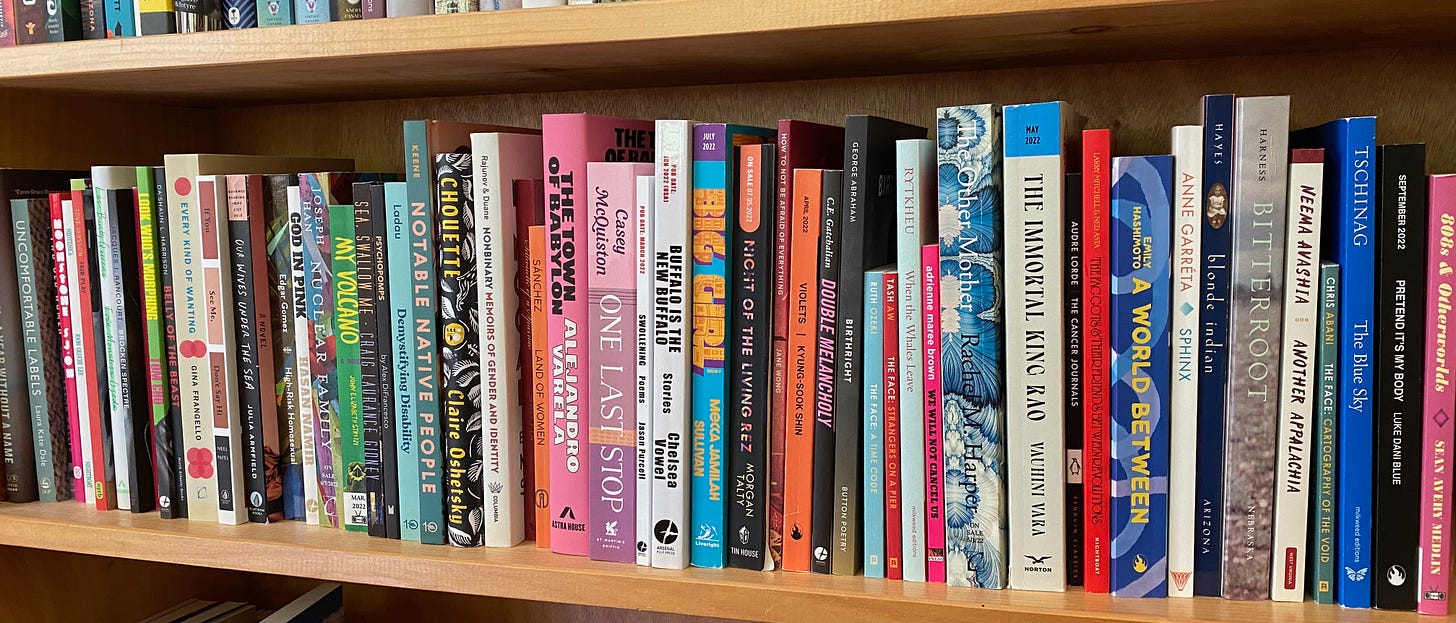

A Picture

This year, instead of putting the books I finish back on the shelves where they live, I’ve been putting them all on a single shelf in my bedroom. It is finally full! It’s extremely satisfying to look at all these excellent books snugged up next to each other.

Around the Internet

If you’re looking for some fantastic queer books to read (and pre-order!) for AAPI Heritage Month, I made a list. I also made a list of some of my favorite queer and Two-Spirit Indigenous fiction.

Bonus Recs: More Books that Talk about the Bad Stuff

Dear Scarlet by Teresa Wong is a beautiful graphic novel in which Wong writes openly and with so much clarity about her experiences with postpartum depression. Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender, one of my favorite YA novels ever, portrays teenagers as the complicated, messy, mistake-prone humans they are.

The Boost

A thread of organizations providing community support in the wake of the white supremacist murders in Buffalo.

Ijeoma Oluo shares some words on gun control and white supremacy.

I am always here for what Chris Newman of Sylvanaqua Farms has to say. His thinking challenges me in the best way.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Every day I watch the red-bellied woodpeckers feasting at my suet feeder. They are one of my favorite birds. I am not a good bird photographer, but my brother is, and he took this amazing photo.

And that’s it until next week. Catch you then!

Love that shot of your bookshelf, Laura -- I'll bet it's so satisfying to look at!