Good morning, book and treat people. Thanksgiving is tomorrow and I will not be celebrating it. It’s a trash holiday, and it’s a holiday I have many fond memories of, especially from when I was in my 20s, farming. I’d cook and cook and cook and my family would cook and cook and cook, and that was a lot of incredible food.

There’s a lot I could say about all of it. The holiday itself isn’t complex—it’s a marker of a genocide, a celebration of genocide, and why are we still doing this? Why? Oh, right. I live in the United States of America, purveyor of violent myths. I don’t think it’s really possible to turn Thanksgiving into something else. I think we just have to stop. But I know how hard it is to just stop. It’s wound deep into the national mythos, and it's wound deep in many families, too. There are a million reasons why just stopping isn’t possible for everyone. It’s a trash holiday, but I don’t think—please believe me, truly—that everyone who celebrates it is a trash human. Of course I don’t.

This year I told my family I wasn’t coming to Thanksgiving, and it was hard, and I will miss them, and as soon as I did it, I felt lighter than I had in a month. My refusal to celebrate Thanksgiving is a small personal choice in a big, connected, broken world. I’m not telling you about this because I want you to applaud my “bravery” or my convictions or any other nonsense. I’m telling you because you know what feels really fucking great? Acting with integrity. I’m telling you because maybe you, too, long for something different. Maybe you, too, long to make another choice. I’m telling you in solidarity and compassion, in the hope that maybe these words can be a bridge, a permission, a beginning. Take them if you need them. I needed these ones and I took them.

Tomorrow I’ll go on a long walk, watch the National Day of Mourning livestream, and spend the afternoon reading books by Indigenous North American and Palestinian authors. None of this is going to stop the bombing in Gaza or return stolen land. But it’s what I’m going to do.

I’m also going to read picture books! Which is what this newsletter (theoretically) is all about today.

The Books

Earlier this fall, I picked up an amazing picture book (Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine by Hannah Moushabeck & Reem Madooh) and realized it had been years since I’d read one. It’s been a hard year for me personally and a hard, grief-filled, rage-filled year in the world. I’m looking for ways to grab joy. I want to make daily joy a practice, as much as I can. Without joy, I can’t fight for justice. I can’t show up for myself or the people in my life.

So I decided that, in 2024, I’m going to read one picture book every day—for joy. The idea came to me suddenly and forcefully, and stuck. I’ve spent the last month compiling a TBR. It was originally supposed to be 365 books but it has already grown far, far longer—I think this is going to be a lifetime project. Working on my picture book TBR is one of the things that’s been keeping me going these last weeks. It’s been a way for me to slip—for a moment here, a moment there—into joy

The official project starts in 2024, but I’ve gotten so excited about picture books as I’ve been making my TBR—so why wait? Why wait for joy? I made myself a list for November and December, full of cozy books, wintery books, Solstice and Christmas books, old books, new books, poetry books, books about hibernation, books about cookies. I put in a million library holds and I started reading.

It has only been four days of this picture-book-a-day ritual, and it is joy, but it’s not just joy. It’s curiosity and growth and reflection and healing and fuel and delight and power and a million other things. I feel like I’ve walked through a door into a new universe. Why don’t all adults read picture books? In love doesn’t even begin to cover it. I am head-over-heels all-out wild for picture books.

Before I get into today’s reviews, a huge and heartfelt thanks to my friend Sarah, who writes one of my favorite newsletters, Can we read?, a joyful celebration of children’s literature. I started reading it long before I thought picture books were for me, a person who does not have and does not want kids. I doubt I would have come up with this project if Sarah hadn’t been in my inbox these past few years.

Finally: here are the first four picture books I’ve read in the order that I read them. I’m documenting my newfound and growing love for children’s literature over at @365daysofpicturebooks if you want to follow along!

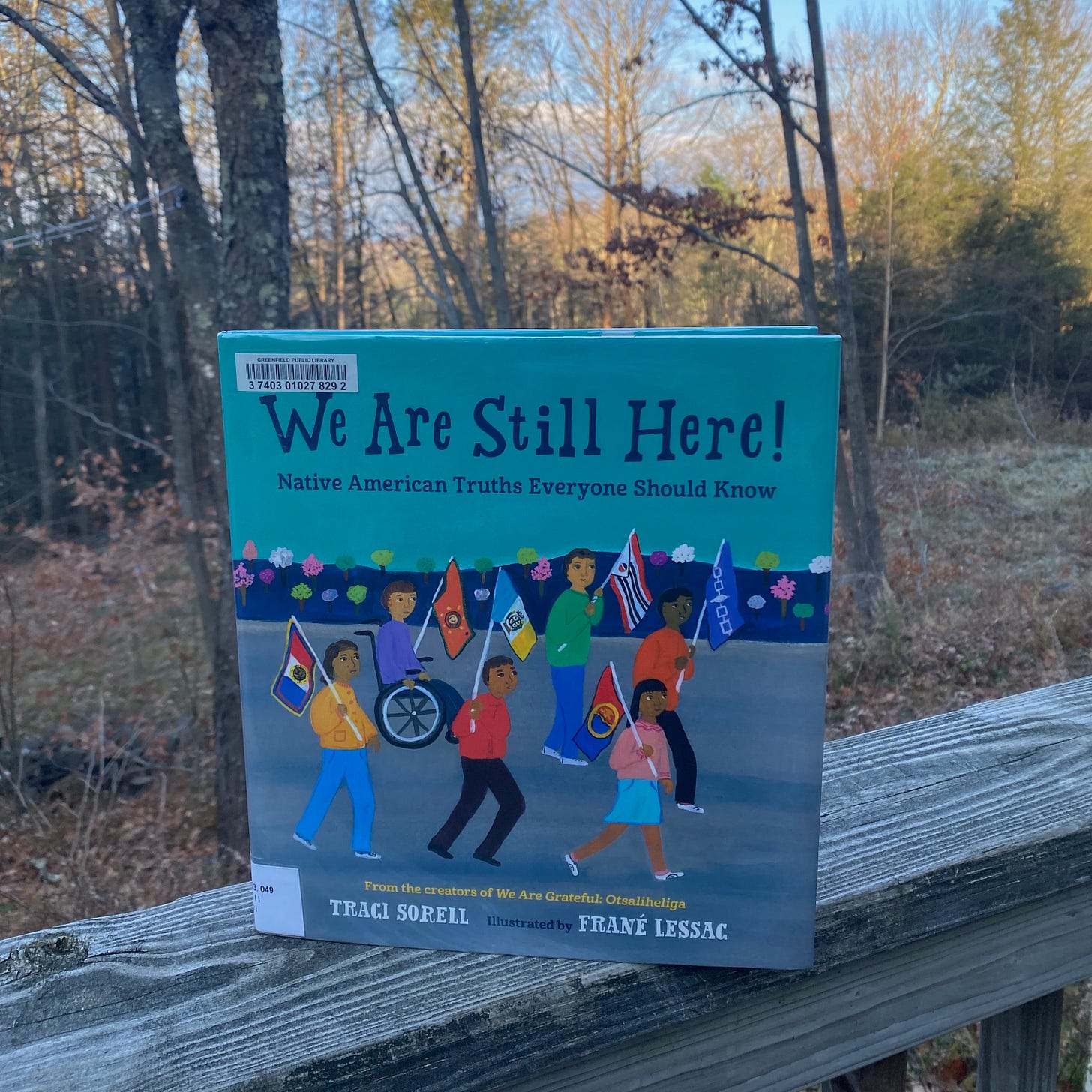

We Are Still Here! by Traci Sorell (words) and Frané Lessac (art) (2021)

This is a wonderful nonfiction book about Indigenous history and, most importantly, the Indigenous present. Children at a community school are preparing presentations for Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Each gets a two-page spread with straightforward text and bright, bold illustrations. Topics include the many violences inflicted by the US government on Native people, including allotment and termination. There’s information on some of the laws the US has passed in an attempt to undue damage (not even close to enough yet), like the Indian Child Welfare Act. There are pages that share how Native people have resisted through tribal activism, language revival, and more.

Each presentation ends with a resounding chorus: “Native Nations say, ‘We are still here!’” I got shivers reading this again and again. It reminds me of a theme that has emerged in my adult reading this year: history is not a linear line to progress. It’s cyclical and messy. With a simple refrain, Sorell captures this truth. No matter what, Native people are here. After disaster, they are here. In the midst of community joy, they are here. After winning court and legislative battles they’re here, and they’re here after losing those battles, too.

The illustrations are wonderful, and enhanced by additional context about them in the back matter. I learned that the picture of families enjoying a day at the beach isn’t just a generic beach, but the Mashpee Wakeby Pond (in my state!). A gorgeous drawing of an educational hike is not just pretty mountains and trees. It’s the Lookout Trail in the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico.

Native people are still, too often, lumped into a homogenous, stereotypical whole. The specificity of the drawings celebrates the beautiful array of distinct cultures, places, religions, and histories that make up Native Nations. I highly recommend this one and I’m excited to read more of Sorell’s work!

I’ll Go and Come Back by Rajani LaRocca (words) & Sara Palacios (art) (2022)

What a warm, tender, delightful book. Jyoti is visiting her family in India for the first time since she was a baby. She’s excited, but everything is unfamiliar, too—loud, overwhelming, new. She gets lonely and homesick while her cousins are at school—until she starts spending time with her grandmother, Sita.

It’s a joy to follow along with Sita and Jyoti as they connect despite a language barrier—Jyoti doesn’t speak much Tamil and Sita doesn’t speak much English. The bright, colorful illustrations show them going to market, playing games, cooking, dancing, and snuggling in bed. When Sita comes to visit Jyoti in the US the following summer, she too feels lonely and lost—until Jyoti remembers what Sita did for her in India. Then they once again spend the summer cooking, dancing, plying games, and snuggling in bed. It’s the same, but different.

I adored the pleasing but moving symmetry of this, and the reciprocity between Sita and Jyoti—it’s not just kids who get overwhelmed and lonely in new places! And I loved the celebration of Tamil, especially the way the story beautifully captures the titular phrase, “I’ll go and come back” in both words and pictures.

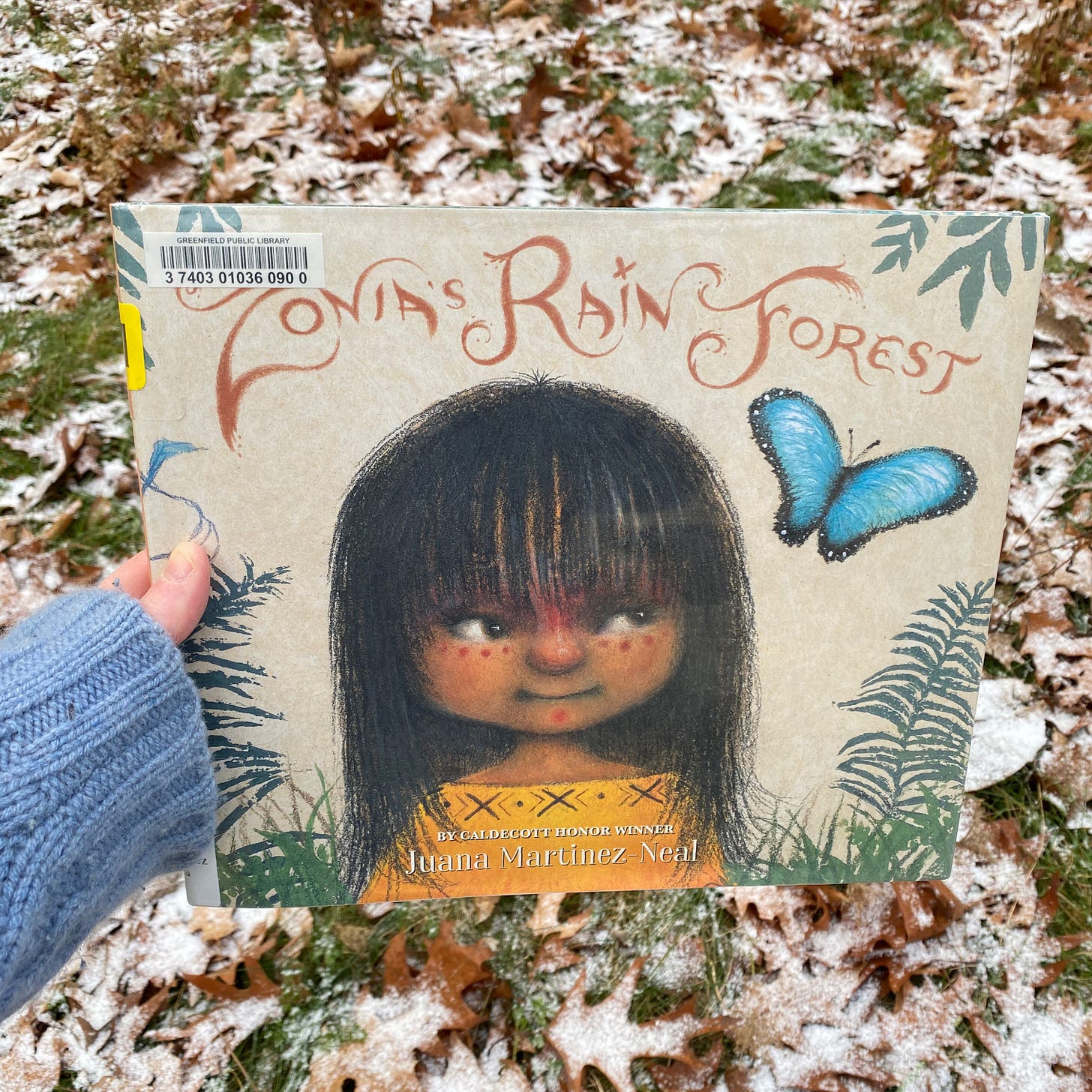

Zonia’s Rainforest by Juana Martinez-Neal (2021)

Zonia is an Asháninka girl who lives with her mother and baby brother in the Amazon Basin in Peru. Every day, her beloved rain forest calls to her, and she answers. She walks through her home, visiting her friends: giant anteaters, river dolphins, two-toes sloths. The illustrations are both muted and bright, full of lush vegetation. I love Zonia’s face, which changes on every page as she runs and plays, but is always full of love, laughter, and wonder.

It’s not until the very end of her walk that she stumbles across a section of logged and decimated forest. Terrified, the runs home to her mother. She tells her mother the forest needs help, and her mother responds that the forest is speaking to her. So Zonia says, “Then I will answer, as I always do.”

This is a simple, straightforward book, but for me it evokes a bedrock truth: all liberation work comes from an ethos of love.

Right now I am burning up with rage at my government’s complicity in Israel’s genocidal campaign against the people of Gaza and all of Palestine. I am incandescent with it. Every day I wake up with screams in my blood. So I channel it as best as I can—I call my reps, I go to protests, I read, I share. I am called to these actions, however small, because my rage is not hollow. It is built, flame by flame, of love.

I love my home wildly, and so I imagine the pain of Palestinian people being forced out of their homes, watching their olive trees burn. I love my niblings with every fiber of my being, and so I imagine the unbearable anguish of Palestinian parents losing their kiddos. My humanity is bound up in what I love, deeply and specifically—people, creatures, hills, trees, little towns. If I did not love—if I were a hollow husk, only concerned with my own well-being, if I did not know, in my body, that my love for others is one of the truest ways I love myself—than I would not be so concerned with the suffering others. I would be able to turn away. I would not wake up with screams in my blood. I loved this book, and you should read it. All liberation work comes from love. Free Palestine.

Other things I loved about this book:

🦥 The back matter contains a full translation of the book into Asháninka, the language of the Asháninka people, the largest Indigenous Nation in the Peruvian Amazon.

🦋 A blue morpho butterfly guides Zonia through the forest.

🐍 In one illustration, Zonia hangs upside-down on a branch next to her friend the red-tailed boa constrictor who helps her “see the world in new ways.” Swoon.

🌳 There’s information in the back matter about deforestation and Indigenous resistance, but the whole book is about the beauty and wonder of the forest. I appreciate what Martinez-Neal decided to give space to, the thing that is going to fuel Zonia’s activism: love.

When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson (words) and Julie Flett (art) (2016)

While helping her kókom in her garden, a young Cree girl notices her colorful clothes, and asks her why she always wears such bright, vibrant colors. Her kókom tells her that when she was a child (“at home in my community”), she always dressed in beautiful colors. But when she was forced into residential school (“the school I went to, far away from home”), she was not allowed to dress this way. She and the other children were required to wear drab, homogenous clothes. The granddaughter wants to know why, and her kókom replies that it was because “they wanted us to look like everybody else.”

She then explains that sometimes, when she and the other children, miraculously, found themselves alone in the autumn, they would gather the leaves into piles and roll around in them, turning their clothes colorful once again. She says, simply, that this made them happy, and that now, she always wears “the most beautiful colors.”

This beautiful pattern repeats throughout the book. The granddaughter asks question after question: Why do you wear your hair in such a long braid? Why do you speak Cree? Why do you spend so much time laughing with your brother? Each time, her kókom responds gently and simply: When she was a girl at residential school, she was forbidden from doing these things. She did them anyway, in secret, when she and the other children were alone. Now, she does them openly, and always.

I knew this book was about residential schools, and because I know how unspeakably horrific those schools were, when I saw the title—When We Were Alone—I associated it with all the atrocities an isolated child could have experienced there: alienation, dehumanization, violence, abuse. What a wonder to discover the true meaning of the title—a celebration of Indigenous resistance. The phrase ‘when we were alone’, which the girl’s kókom repeats in every answer, evokes how children survived what is unsurvivable—by creating their own worlds. The rhythmic repetition becomes a song, not just of survival, but of joy.

I can’t stop thinking about the way the story braids together intergenerational trauma and intergenerational wisdom, love, resilience, power. It’s so gentle, so simple and direct, and yet it cuts deep. The illustrations of the residential school are subdued and dark, while the illustrations of resistance and togetherness are bursting with color. I felt the shift as I turned each page. As far as I’m concerned, this is a perfect picture book, as layered and thoughtful and moving as many adult novels I have read.

The Beyond

November Treats

I made a delicious pumpkin crumb cake, but I did not take any pictures of it. I made a very simple squash soup, with onions, garlic, garam masala, and coconut milk, but I did not take any pictures of it. Yossy Arefi’s new cookbook is finally out and I can’t wait to get my hands on a copy.

Recent Audiobooks

I finished Thistlefoot, which was a bit of a slog—it went on and on and the characters didn’t have a lot of depth—but it has a gorgeous ending that made me cry. It’s a meditation on stories and memory and the power they hold, on what it takes to remake cycles of violence and trauma. If you’re more of a fantasy/folktale reader than I am, it might not drag so much for you.

Yesterday I started The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappe, read by Paul Boehmer. It’s very good, but I can only listen to it in small doses because it’s so devastating and enraging. I’m also listening to Second Chances in New Port Stephen by TJ Alexander, read by Aden Hakimi & Feodor Chin. It is a total delight, by far my favorite TJ Alexander so far. If you’re looking for a joyful but real trans romance, it’s out December 5th.

Further Reading

In addition to watching the livestream of the National Day of Mourning, I’ll be reading a whole bunch of Indigenous picture books on Thanksgiving. Here are six I’m really excited about.

My Powerful Hair by Carole Lindstrom & Steph Littlebird

Remember by Joy Harjo & Michaela Goade

We are Grateful by Traci Sorell & Frané Lessac

Winter’s Gifts by Caitlin Curtice & Gloria Félix

We are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom & Michaela Goade

Stand Like a Cedar by Nicola L. Campbell & Carrielynn Victor

The Bookshelf

Around the Internet

On AudioFile, I wrote about some recent funny books with substance.

A Taste of the Commonplace

This week I looked up ‘grief’ in my commonplace book, and this line from Grievers by adrienne maree brown—well. “Heartbreak for the living is still full of possibility.”

And Beauty

First, some words I’ve been sitting with this past week, and additional resources.

I know I’ve shared Fatimah Asghar’s newsletter before, and I’m doing it again. They wrote this article in late October for an international media website, which then decided not to publish it when they come under attack for their pro-Palestine stance.

Radical queerness rests on a foundation of valuing human life, of each other’s contributions, where we can honor that, where we can nourish, where that can grow. All systems of oppression are linked together, and so are the liberation movements that dream against them. Believing in a shared future that some call ‘naive’ is queer, in and of itself. So many others share this dream with us collectively. We dream it with strength, with courage, with the conviction of the sun.

“On Literary Empathy and the Performative Reading of Palestinian Authors” by Etaf Rum (Lit Hub)

“Witnessing Gaza Through My Instagram Feed” by Zaina Arafat (Intelligencer): “To watch is to consume; to witness is to acknowledge, to bestow some degree of legitimacy. But what does it do to see it? Is empathy ever enough?” Please read this one.

The We Here collective has put together a comprehensive document of resources for education and action around Palestine. You can access it here. I learned about it from the ever-wonder Enthusiastic Encouragement & Dubious Advice newsletter.

“Gazan Family Letters, 2092” by Mosab Abu Toha (The Nation): Toha is a Palestine poet from Gaza. He was kidnapped by the IDF while trying to cross into Egypt with his family and—thankfully, my god—released a day later. I don’t have words for any of this. Please read his work.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: The light, the light, the light. We are on the cusp of the Season of Light, and my cracked heart is full, bursting, overflowing with it.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! Next week I’ll share my November reading reflections (like I did in September and October). All issues of this newsletter will be free through the end of the year, but if you want to support my work financially, you can subscribe here.

Reading picture books again as an adult is so joyful! I love this idea. Solidarity for no thanksgiving celebrations from someone in the UK - the holiday has always really confused me as a non American. I hope you have a wonderful walk tomorrow ❤️ and that final picture of your dog is absolutely glorious!

Thank you, Laura, for calling out this sad "holiday." I'm celebrating by rereading David Silverman's book This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving and listening (again) to @Ben Tumin's fine interview with him: https://skippedhistory.substack.com/p/professor-david-j-silverman-on-the-897