Greetings, book and treat people! I am deep into my book cataloging project and it just keeps getting more and more involved. We are also slowly creeping into fall which means I! am! waking! up! I’m repainting bookshelves and working in my garden and dreaming up day trips to visit friends and taking a class and I just joined a queer chorus and soon I’ll be deep in planning for Cookie Extravaganza. Which is all to say, I’m reading less, and that’s healthy for me. It gives me an excuse to talk up some of the brilliant books I read over the summer and haven’t reviewed yet.

Speaking of brilliant books, the 2022 National Book Award longlists were just announced and though I don’t care about book prizes, and don’t pay attention to them (beyond what I absorb from being on Bookstagram), the fiction longlist has me excited. Two of my favorite books of the year are on it (All This Could Be Different and The Town of Babylon). All This Could Be Different, especially, is a book I love more fiercely than I love most books. I know that doesn’t mean I’ll love the rest of the books on the longlist, but it does peak my interest. I have never in my life been tempted to read a longlist, but I’m going to read this one! I put them all on hold at the library. I’ll report back.

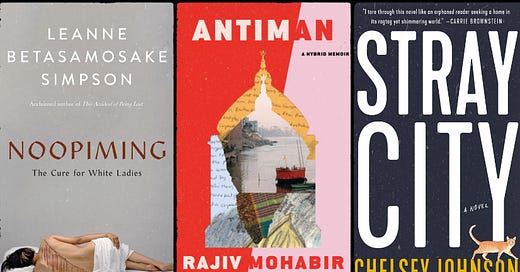

As far as this week’s books, they’re all made up of different kinds of building blocks. Noopiming uses white space in ways that have me rethinking what novels are made of. Antiman is about the building blocks of a life, and also the building blocks of language and translation. Stray City is about the building blocks of queer family.

The Books

Backlist #1: Antiman by Rajiv Mohabir (Memoir, 2021)

Mohabir describes this book as a “hybrid memoir” and I’ve been thinking about what that means for a while now, especially in the context of all the forms of in-betweenness Mohabir explores. It’s most apparent, at first, in the form the book takes, which is agile and beautifully scattered. There are long, lyric essays; journal entires; poetry and prose poetry; short recollections; vignettes and sketches of moments, people, and places; and transcribed songs taught to him by his grandmother, written on the page in her language, Guyanese Bhojpuri, and sometimes translated into English. There is a lot of language blending throughout the book, with sections moving back and forth between Hindi, English, Creole, and Guyanese Bhojpuri.

But the idea of hybridity is also reflected in the substance of the book. It’s a memoir about Mohabir’s journey to understand himself, his place in the world and in his family. He’s trying to tease apart the threads of how he came to be, the messy strands of history, migration and forced migration, colonization, religion, and language that live in his body, that are his living story. He wants to know what it means to be a queer Indo-Guyanese writer living in the U.S., what it means to live in diaspora or in exile, what it means to lose and relearn a language. These are questions with tangled answers, and that’s part of what makes the form of this book so enlivening. There’s no destination. Rather, Mohabir invites his readers to witness the journey.

There’s so much here—a beautifully written and heartrending essay about an abusive boyfriend; essays about his strained relationship with his extended family; a recollection of a trip to India he took in his early twenties; a piece about the deep sense of connection and possibility he felt working with other young South Asian activists in New York. These sections are grounded, with rich sensory detail and easy-to-follow arcs. But they’re surrounded by more fluid writing that’s surprising and non-linear, poems rooted in felt realities rather than physical ones. In these sections Mohabir explores queerness and spirituality, ritual and song, his longing to belong inside places and language, and more. This is the kind of inventive writing I mean:

// There are river dolphins in the Ganges // There are river dolphins in Guyanese rivers // Your echolocation vibes with both species // How queer for a dolphin to live in a river // Diaspora is a queer country // How can you be at once two species from two places //

The most powerful parts of this book are the sections about language—it’s all about language, really, but Mohabir is at his best when he’s addressing just how central language is to our understanding of self. All of his wandering, wondering, and seeking is is driven by his desire to preserve and translate his Aji’s songs. About his Aji, he writes:

She was born in 1921, was the grandchild of indentured laborers, and spoke as her first language a form of Bhojpuri blended with Awadhi called Guyanese Bhojpuri. This language, which falls under the larger category of what is called Caribbean Hindustani, is unique to her speech community and descends from North Indian languages with words borrowed from her colonizers. I was lucky enough to learn as much as I could before she passed.

Mohabir traces the history of his Aji’s language and its loss across continents and centuries, through the violences inflicted on its speakers and the joy hearing its music has brought to his life. And it’s through this history, a history of translation and colonization and movement, resilience and dance and death, that he find his way back to himself, and into a future.

Early in the book, he writes: “She left me no guitar, no sitar, no flute. Just these two hands and my tongue. If we forget our ancestors, they disappear. We disappear.” He goes on to say: “I want to believe that her language—our language—isn’t dead.” I am no linguist, but to me this book feels like reincarnation. Through the act of writing, Mohabir declares that his Aji’s language—and his—is alive and breathing.

Backlist #2: Stray City by Chelsey Johnson (Fiction, 2019)

If you’ve been around here for a little while you know how much I love a queer family novel, so I’m not sure why it took me so long to get around to reading this one! It’s now one of my favorites.

It’s set in Portland, Oregon in the late 1990s. Andrea is a lesbian who sleeps with a man after a bad breakup, and…keeps sleeping with him. She’s not attracted to him, she’s not even sure she likes him, exactly, but there’s something about him, and their not-relationship, that’s alluring. She falls into it, maybe because it’s easy or because it’s numbing or because it’s new, even though it makes her feel disconnected from herself and her (often judgmental and casually biphobic) chosen queer family. This goes on for a while and then she gets pregnant. And then she decides to keep the baby. And that’s not a thing that lesbians in her circle of artists and radicals in 1990s Portland do. So it all gets very complicated and painful and tangled.

Oh, there’s just so much I love in this novel, and so much about it that feels true in ways I don’t see that often, even in queer fiction. I love that Andrea is a lesbian who sleeps with a man and is still a lesbian, and that this hetero relationship doesn’t send her into an identity criss (she tells Ryan on multiple occasions that she’s a lesbian and always will be). It sends her, instead, into a community crisis. She knows who she is, but once she starts doing something that her people deem unacceptable, she loses a piece of herself, the piece that’s held and made whole by being a part of them. Things get weird at family dinner. When she decides to keep the baby, she doesn’t get much support, at first. The queer people in this book are not welcoming and inclusive and accepting. They’re often bitter and unforgiving. They gatekeep and ostracize and make cruel jokes and seem to be afraid of nuance and contradiction. Andrea observes this and names it, even though, at times, she agrees with them, and is disgusted by herself and her own actions.

It seemed in our urgency to redefine ourselves against the norm, we’d formed a church of our own, as doctrinaire as any, and we too abhorred a heretic.

Andrea, who was rejected by her family of origin, and then spent years building this queer family of choice, finds herself suddenly cast out by them when she needs them the most. This is the conflict that lies at the heart of the book. It’s not about Andrea figuring herself out (though there’s plenty of that), and it’s not really about her relationship with Ryan. It’s about this rupture between her and her queer family, and the work it takes to repair it.

Don’t worry; it’s not all so grim! Everyone is very young and, guess what, they grow up. They make mistakes and make amends and soften, and, eventually, put their family back together. The last third of the book unfolds after a ten-year time jump, which works brilliantly. It’s a structure that highlights the most emotionally intense and tumultuous periods in Andrea’s life, as well as the intense change that comes with having a baby.

Family-making of any kind is hard. I love the way Johnson complicates it in this novel. Nobody is a villain, not even Andrea’s estranged parents, who end up playing an important role in her life. And nobody is perfect, not even Andrea’s best friend. The family Andrea eventually settles into takes time and work and space. It’s not the one she imagined as a little girl in Nebraska, or when she arrived in Portland as a baby dyke, desperate for queer community, or when she found herself unexpectedly pregnant at 24. It’s a mix of all of those imagined families, and it’s something entirely its own, unexpected, surprising, and still changing, even as the novel ends.

Backlist #3: Noopiming by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Fiction, 2021)

It’s hard to know how to write about this book, which I loved and felt deeply and can’t wait to return to. I remember the feeling of gratitude and revelation I had upon finishing Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq, and I had a similar feeling reading this book: how incredible that I get to hold a story like this in my hands, that I get to experience a little piece of it. Simpson’s storytelling is Nishnaabeg storytelling, storytelling steeped in Anishinaabe culture and traditions, storytelling that joyfully, playfully, assuredly ignores all western conventions. It’s the kind of book that will get slapped with the label “experimental”, but I don’t think it’s experimental at all. It just exists outside of what so many of us have been trained to expect from novels.

The book meanders and spirals. Seven characters narrate events and describe the world around them. These characters represent different parts of Mashkawaji, a being who lies trapped under ice, and seems to be remembering (experiencing? imagining? time blurs and twists in this book) their life in the world above the ice. There’s Mindimooyenh, an old woman; Sabe, a giant; and two humans, Asin and Lucy, among others, human and non-human.

In the first chapter, Mashkawaji narrates directly, explaining where and who they are, and the relation each of the characters has to them. (“Sabe is my marrow.” and “Adik is my nervous system.”) For the rest of the book, these characters take over. The name of each speaker appears at the top of each page, followed by some text. Sometimes it’s a paragraph or two. Sometimes it’s only a sentence. They talk about geese and storytelling and loss and what is sacred, about ceremony and errands, about the parks scattered throughout the city, and grief and parenting and each other.

Many of these pages feel like small poems, little bits of truth and beauty, pain and delight:

“Mindimooyenh says: ‘Grief is saving yourself over and over again.’”

“Adik’s favorite sound is ten thousand hooves hitting the ice. Imagine. You can’t even.”

There’s a wonderful spark of humor and sharpness in so much of Simpson’s writing. The book feels dreamlike at times, but it’s also grounded, physical.

Ceremony strengthens the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for emotional regulation and empathy. Ceremony is not just one big dumping ground of sharing circle. It is not a performance. It is not even necessarily designed to make you feel better.

The white space is astounding. What does it mean to read a story that contains as much emptiness as it does text? What exists in the emptiness? The white space makes this 350-page book quick to read, but I took it as an invitation to slow down. After a while, all of those long blank pages began to feel a different way—not empty, but full of whispers, and the kind of silence that holds meaning. So much of the story takes place in those long pauses, the stretches of not-emptiness between the words. I found myself lingering over sentences, or simply staring at the page in front of me, waiting for some sign from within, permission to turn the page, to go on.

I’ve been thinking constantly this past week about the idea of disfluency, thanks to the incredible work of poet and musician JJJJJerome Ellis (there are links to his work in The Boost). I’ve been thinking about normative and non-normative speech and disabled and abled speech, and about the expectations we place on each other about how to tell stories, how to communicate, how to do language. Ellis writes about disfluency as possibility, rupture as possibility. His disfluent speech builds portals and opens worlds that are not otherwise possible.

Noopiming, to me, feels disfluent in this way. It invites us to reimagine how stories can be told, and, perhaps even more importantly, how stories can be listened to. I could not read this book the way I usually read novels. It required me to recalibrate, rewire.

Of course, I am not fluent in the traditions and culture Noopiming stems from, and so what feels full of potent, revelatory disfluency to me likely feels very different to Nishnaabeg readers. But this, too, seems part of the magic of disfluency, and of reading, speaking, listening, and experiencing, outside of our own ingrained fluencies. There are infinite pathways into and out of a novel like this, and mine was only one of them.

The Bake

The Great British Bake Off is back! I watched the first episode last week and thoroughly enjoyed it. Last year, I ran into trouble a few times when I started watching an episode without dessert on hand. This year, I’m more prepared. I made this cake before work Friday morning to ensure I’d have something to snack on while watching! It’s a lovely fall cake: buttery, nutty, toasty, chocolatey.

Toasty Pecan & Chocolate Cake

Adapted from—you guessed it—Snacking Cakes by Yossy Arefi

Ingredients

1 stick (113 grams) unsalted butter

150 grams (3/4 cup) brown sugar

2 eggs

165 grams (3/4 cup) sour cream (the original calls for yogurt, feel free to swap)

1 tsp vanilla

1/2 tsp salt

A few grates of nutmeg

160 grams (1 1/4 cups) all purpose flour

1 1/2 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp baking soda

75 grams (3/4) cup pecans, toasted and chopped

85 grams (1/2 cup) bittersweet chocolate, chopped

1 Tbs turbinado sugar

Preheat the oven to 350. Butter an 8-inch square pan and line it with parchment so that it hangs over the edges on two sides.

In a small saucepan, melt the butter over medium heat. Keep cooking, stirring frequently, until it turns golden brown and starts to smell nutty. It usually takes 3-5 minutes. Watch it carefully! Pour the browned butter into a large bowl and set aside to cool for a few minutes.

Add the brown sugar and eggs to the butter (it’ll probably still be warm, that’s fine) and whisk to combine. Mix in the sour cream, vanilla, salt, and nutmeg, and continue whisking until everything is smooth. Add the flour, baking powder, and baking soda, and whisk again. Fold in about 2/3 of the pecans and 1/2 of the chocolate. How much you fold in is up to you—the rest will get scattered over the top, so it depends on what you like.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan. Scatter the remaining chocolate and pecans over the top, followed by the turbinado sugar. Bake until the top is golden and a tester inserted in the middle comes out clean, about 35 minutes. Let cool on a wire rack before gently lifting the cake out of the pan. I think it keeps for a while, but I really wouldn’t know.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Dressed-Up Party Baba

I had dinner with some dear friends and their eight-month old last week, and wow, it’s been a long time since I cooked something to bring to a lowkey potluck. It was a joy. This is what I made. Is it a meal? Well, no. But it’s delicious.

I like to roast everything with the eggplant—it makes blending it all together a snap! Cut two eggplants in half and place them cut-side down on a baking tray. Quarter 2-3 onions and add those to the tray. Cut off the top of a head of garlic and toss it on. Drizzle everything with olive oil. Add some salt and pepper and a sprinkling of cumin seeds. Roast at 450 until everything is soft, about 40 minutes. Once the eggplant is cool, scoop out the flesh and put it in a food processor, along with the onions and oils from the pan. Squeeze out the garlic cloves and add those. Add a few tablespoons of olive oil, the juice of a lemon, and 2-3 tablespoons of tahini. Process until smooth, and adjust the seasonings to your liking.

To make the toasts, slice some thick crusty bread into bite-sized pieces. Drizzle with olive oil, and sprinkle with salt, Aleppo pepper, sesame seeds, and sumac. Broil until crisp and golden, about a minute. I like to top baba ganoush with olive oil, paprika, and pine nuts to dress it up. Chopped parsley is also nice!

The Beat: Prairie Fires by Caroline Fraser, read by Christina Moore

Remember how last week I said I was choosing between All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt, Man o’ War by Cory McCarthy, and Silence by Jane Brox for my next listen? Surprise! I picked up this 20+ hour biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder instead. It’s a fascinating, critical look at both Wilder’s life and the intense myth-making that went into the Little House series. Fraser places Wilder firmly in a historical context that is absent in Wilder’s own books. The book begins with the Dakota War of 1862 and the mass execution of 38 Dakota men—the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Fraser forefronts the history of the Indigenous people whose stolen land Wilder grew up on. She also highlights the poverty, uncertainty, and hardship that defined Wilder’s childhood—hardship that is romanticized and sanitized in Wilder’s novels. I’m only halfway through but it’s superb so far.

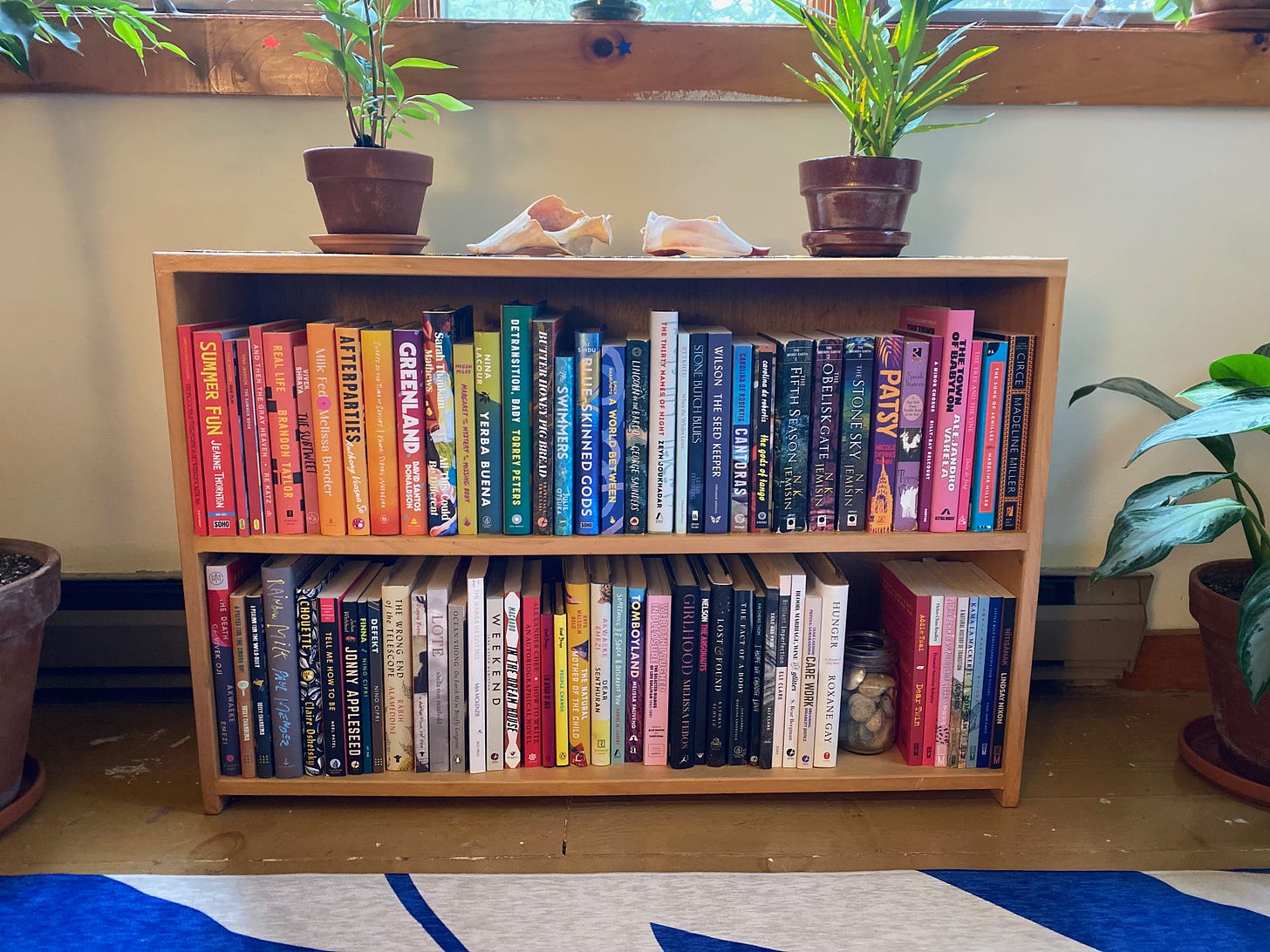

The Bookshelf

A Picture

Book cataloguing, reorganizing, and weeding has taken over my life. It’s such a satisfying project! Over the weekend I filled this shelf in my office with all of my most beloved books. I can’t stop looking at it.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I rounded up some of my favorite place-based memoirs.

Bonus Recs: Building Blocks

I’m slowly working my way through Rabih Alameddine’s entire backlist, in chronological order. Last week I read Koolaids, his first novel. It’s a weird, uneasy, fascinating book. I haven’t decided exactly how I feel about it, but one thing I know for sure is that I love the structure. It’s made up of all these disparate parts that come together in ways I’m still untangling. It’s really something. Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades is a recent book that does a similar thing, though in a slightly less dizzying way.

The Boost

I’m taking author Callum Angus’s *sigh*ence class this fall. It’s hard to describe the class, which is a mix of writing and science and magic, but it is magnificent. My brain is buzzing and my heart is awake. So much came up in the first session!

This album by JJJJJerome Ellis is breathtaking. Is it poetry? Spoken word poetry? Music? An essay collection? Yes and. It is incredible, one of the most amazing pieces of art I’ve experienced in a while.

Some books mentioned by people in class that I am excited to check out: Plans for Sentences by Renee Gladman, To See the Earth Before the End of the World by Ed Roberson, and Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry edited by Camille T. Dungy.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: As part of my book cataloging project, I repainted a bookshelf! It’s my first time using a stencil like this, and it’s not perfect, but I’m so happy with it.

Catch you next week, bookish friends!

Your bookshelves are so lovely! Your cataloging journey is a delight to watch.

*drools* omg that cake!!! i'm starting bake-off tonight and cannot wait!! Also I love updates on your cataloging project—mine is absolutely unhinged and I need to get a handle on it, and you're helping my brain work up to tackling it! I think it's going to be my indoor winter project :)