Volume 2, No. 32: University Presses + Chocolate Zucchini Cake

Greetings, book and treat people! It cooled down over the weekend, and while I’m sure it’ll get hot again soon, the reprieve gave me life. I baked, I took a long walk, I put on a long sleeved shirt. It was heaven.

It’s been a while since I’ve done a bird update! Earlier this summer a subscriber reminded me that the Merlin Bird ID app has an incredible sound ID function. I’ve been using it daily ever since, and I’ve learned so many new bird calls—tufted titmice, red-eyed vireos, gray catbirds, ovenbrids, eastern wood-pewees, ravens. Many of these are birds I hear almost every day. It is miraculous, sitting on my porch, listening to the music of these creatures with whom I share this land, knowing their names. Birdsong, bird chatter, bird calls, the loudness of the forest all around me—it’s been a highlight of the summer.

The best bird moment of the summer so far happened a few weeks ago while I was on Nantucket. I was walking on a favorite loop when a small raptor I didn’t recognize flew directly over my head, calling loudly. I whipped out Merlin and it immediately identified the bird: a merlin! It turns out there was a nest nearby, which my dad found the next day. I went back several more times and got a good look at the two adults and the juveniles. They are gorgeous, majestic birds.

I also love university presses! I didn’t even realize how many amazing books these presses publish until I started tracking publishers on my reading spreadsheet. Like other independent presses, university presses are out here publishing so much innovative, unusual, challenging queer work. These are just three of the many amazing university press books I’ve read this year.

The Books

Backlist: Dark Tourist by Hasanthika Sirisena (Essays, Ohio State University Press, 2021)

This is a wonderful, rigorous collection of essays about place, illness, disability, change, art. Sirisena writes about her Sri Lankan heritage, her childhood in North Carolina, and her complicated relationships to these places, her family, her culture. She weaves stories of her own life and her family’s life with broader stories about American imperialism, disaster tourism, the legacies of war, queer culture, how we talk about sickness, making art. I love the deftness of this, the way she zooms in and out. Her writing is vulnerable and intimate one moment, analytical and philosophical the next.

In ‘In the Presence of God I Make this Vow’ she writes about her father and her stepmother’s marriage. She’s trying to help her father’s wife become a citizen, but no one believes they’re truly married because for three years they didn’t tell anyone, not her or her sisters. She interweaves this story from her family with the story of a couple in 1590s England who married suddenly and then kept their marriage secret. These two families, cultures, and situations are so different. In weaving them together Sirisena tells a much bigger story about secretary, privacy, patriarchy, silence, state intervention, the sorrow of not being able to speak truth because of what it will cost you, the purpose of marriage.

I love reading essays about art, especially when artists write about the art that matters to them. It’s a window into their process, their way of thinking. It makes the world feel bigger. I’m never going to study all the art in the world closely, so there is something intimate and wonderful in reading about other artists who are grappling with art, and how they’ve been influenced by other people’s work.

‘Six Drawing Lessons’ is a beautiful reflection on a series of lectures given by the South African artist William Kentridge, his influence on her life and work, and the trajectory of her creative life. I can’t say I care deeply about this artist now, but I loved the agility of this essay. It’s about why we make art, why Sirisena has made art, why talking about art matters.

‘The Answer Key’ is a series of terms, numbered—famous queer people, works of queer art, sex acts, moments in queer history. It’s one big block of text. The first line reads: “Bonus Puzzle: CIRCLE BOLDED LETTERS TO REVEAL A SECRET MESSAGE.” At the end of the essay, the secret message is revealed, and it gutted me. It’s astounding that a collection of terms, not random, but extremely dense, becomes this intricate essay about identity simply because of how it ends. It reminds me just how expansive form can be.

In ‘Confessions of a Dark Tourist’, she writes about going on a tour of former war zones in Jaffna, in the north of Sri Lanka. It’s an example of what I love most about her writing, because she works through so much in the essay. She doesn’t flatter herself. She feels uneasy about the tour and the implications of war tourism, but she goes anyway, and the essay becomes a piece about guilt and shame and the difference between looking at something and witnessing it, being a part of something and being outside of it.

‘Amblyopia: A Medical History’ is a structurally fascinating look at illness, injury, disability, and language. Sirisena was in car accident as a teenager in which she suffered serious brain trauma that led to a lasting eye injury. The essay unfolds in many short sections with incredible titles, like ‘I try to Use My Lazy Eye for Personal Advancement' and ‘John Milton Receives No Answers, Part 1’. It’s a collection of moments reflecting on what it means to have an impairment, to be healthy or ill, what beauty is, how our relationships to our bodies change over time. It’s such a complete and complex a portrait of her shifting understanding of her own identity.

The other thing that’s lovey about this book is how quietly queer it is. She’s bisexual. She never writes about coming out. She doesn’t write about relationships in depth, either. Dates and partners of different genders come up. She touches on the ways her queer identity has mattered to her, has changed over the years. She writes about longing for language she didn’t have for her kind of queerness as a teenager and young person. But this is mostly a book about making art, about sickness, about family webs and culture. It’s always so refreshing to read books like this where queerness is just another piece of the puzzle, flitting in and out of the narrative like everything else.

Frontlist: Lote by Shola von Reinhold (Fiction, Duke University Press)

I don’t know what to say about this book. I want to say everything about this book. I want to say nothing about this book because what can I say? I’ll say this: I love it absolutely. I’ll say this: it’s weird. I’ll say this: it’s singular.

Mathilda is a Black queer artist/archivist/aesthete fascinated (though fascinated is far too tame a word) by various artists and writers who were active in Europe in the 20s and 30s, namely the Bright Young Things and the Bloomsbury Group. She calls these obsessions her Transfixions—not only is she enamored of their work, their lives, their stories, but thinking about them elicits certain sensations in her body, i.e. “Internal fumes / pale blue ethanol vapours.”

While volunteering in an archive, she discovers a photograph of Hermia Druitt, a forgotten Black modernist who no one seems to know anything about. Hermia becomes Mathilda’s most enduring and powerful Transfixion. Her research into Hermia’s life leads her to a mysterious (and extremely strange) artists’ residency in Dun, a small European town (in what country? unclear) where Hermia once lived.

The books I love most are always the ones that move me deeply, that leave me weepy or bereft, the ones I can’t stop reading because I am so utterly invested in the characters. I often admire books I don’t feel this way about—books that do interesting things with form, that feel new or surprising, that are challenging and complicated and make me think about language in new ways.

But every so often—exceedingly rarely—I come across a book that does both these things. The last book that did this for me was Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders, which I read in 2018. Lote is a book like that. It is an astonishing work of imagination and heart, a book that seems to reinvent itself—and form—on every page. It is so smart, smart enough that I know I’ll have to read it again and again in order to untangle all of it. I was in a perpetual state of awe while reading it. My brain buzzing. My fingers itching. Every cell in my skin alive. My throat dry. As a writer and a human who loves words, this is what I crave above all else while reading: this feeling that I’m in the presence of greatness, that I’m experiencing something inimitable.

And. And I was so caught up in Mathilda’s story. I didn’t want to stop turning pages. I was all in for her, Team Mathilda, I needed her to be okay. I laughed and cried and had to put the book aside and pace around the house because of all the feelings, because despite the strangeness (there is so much) and the philosophy (a lot) and the art talk (about art history and art movements I don’t know much about) I felt every page of this novel in my bones.

Competence is sexy, right? This debut is so assured. It is exactly what it wants to be, exactly itself. The writing is flawless, and by flawless I mean that I knew, from page one, that von Reinhold put down on the page exactly what they intended, that they placed every word exactly where it was supposed to be placed. This book does not waver.

Lote is concerned with the past, especially the past as it relates to Black art and queer and trans art. It’s about the historical record, who makes it and who gets left out of it. It’s about luxury and excess and who gets to embrace them. It’s about erasure and reclamation and transformation. It’s about the importance of having a Black, queer, trans archive, and what it means—for the present, for the past, for the future—that such archives have been systemically destroyed.

It contains excerpts from a (fictional) nonfiction book about Hermia’s life, and another work, less clearly defined—a novel-within-a-novel, maybe. It is extremely intertextual. It’s full of references. It engages with the work of made-up people, as well as real writers and artists (Richard Bruce Nugent, Stephen Tennant, Virginia Woolf). It is dense with memory and lineage and history. It blurs so many lines and then it becomes its own archive.

And yet, for all of that, there’s this element of (and I don’t know how else to say this): Fuck you, I do what I want. That’s what I imagine Shola von Reinhold saying to the world. It’s not a criticism. It’s what makes this novel so extraordinary. There’s no pretense. It’s like there wasn’t an existing literary vessel for what they wanted to say, so they made a new one. Phoenix-like.

Upcoming: Making Love with the Land by Joshua Whitehead (Nonfiction, University of Minnesota Press, November 15th)

I’ve been reading a lot of wonderful books recently that I am hesitant to review, partly because they grapple with the purpose of storytelling and literature, especially queer and Indigenous literatures, and how they are read in the context of settler colonialism and white supremacy. It isn’t that I don’t want to engage with these works—in fact, I hold it as my responsibility to engage with them—it’s that to engage with them in a meaningful way requires slowness and rigor, perhaps a reworking of the very way I read. I want to tell you about this book because I love it, but I’m not ready to really get into it, because I’m still untangling it, because I’m still trying to figure out how to untangle it. I could say the same thing about Lote, honestly.

This is a beautiful book of essays—though as Whitehead explores in one piece, “essays” isn’t the word, and perhaps there isn’t a word in English for the kind of work he’s doing here. It’s about kinship and grief and covid and language, about the theory and practice of Indigenous literatures, about Whitehead’s previous work, about the violences/confines of genre, about disordered eating and sexual violence and healing. (In the first iteration of this paragraph, I wrote, accidentally, “disordered healing”, and maybe this book is about that, too—nonlinear healing, ongoing healing, the messy intersections of old beginnings and new endings.)

I underlined about a thousand passages, and instead of adding my own interpretations, I’ll just share a few of the many I’m still thinking about. Whitehead writes about writing—storytelling, word-making—with so much detail, grace, and thoughtfulness. It’s these sections that make up the heart of the book. Both of these passages are from the brilliant piece ‘Writing as Rupture’:

Here too, our concepts of auto and biography are braided together through the act of writing and of marking: a pictograph or a petroglyph are story, historical, and communally so, because the body of the storyteller is never removed from the bodies of their landbase, riverbase, oceanbase. Knowing this, I have never sought to call myself novelist, poet, essayist, or academic. Rather, I have pinned myself to the concept of an otâcimow, a storyteller, something that may sound simple in English but in nêhiyâwewin denotes in its root, otâci, that we are not only storiers but also legend-speakers. Which is to say we are historians and cultural theorists, informers; which is also to say we are academics and researchers and confessors; which is also to say that we are journalists and poets. If autobiography within Western linguistic systems is an obituary, then in nêhiyâwewin it is a wildly engendered genre of return- ing and of revival; of transplanting the past into the future and glimmering in the hope of “now.”

I would argue that words, orality, sound itself are kin to us since we not only breathe animation into language, but we also enliven stories through the deployment of our voices, senses, bodies. The act of speaking summons words into being through an entanglement of experience, memory, and recognition. And stories become communal through a schematic of ethics that holds us accountable to our relations; words themselves become these animate kin. In this way, stories play a key role in the development, empowerment, and futurity of Indigenous peoplehoods. wahkohtowin is enacted again precisely because storying is directly aimed at community development and health—something, I would argue, that differentiates Indigenous stories from European literatures, which are so often consumed in a solitary fashion.

I thought a lot about Billy-Ray Belcourt’s upcoming (and brilliant) novel A Minor Chorus while reading this. These two books feel like they belong together; I’m excited to revisit them both. I’m also thinking about Elaine Castillo’s How to Read Now, a book I haven’t read yet, but it’s very high on my list. I’m curious to see how my understanding of some of the books I’ve read recently (and of myself as a reader) changes after reading that one.

The Bake

I made that chocolate zucchini bread I was planning to make last week! Well, it’s not a bread. It’s a dark, decadent, moist chocolate cake that takes about twelve minutes to mix up. It’s not very zucchini-y, but don’t we all need some not very zucchini-y recipes this time of year?

Simplest Chocolate Zucchini Cake

Adapted from Jesse Szewczyk via NYT Cooking

I am currently out of all-purpose flour, and instead of buying more, I just keep using other kinds of flour instead. That’s what I did here, and it’s tasty, but you can obviously use all-purpose instead.

Ingredients:

2 eggs

330 grams (1 1/2 cups) light brown sugar

3/4 cup neutral oil (safflower, sunflower, vegetable)

2 tsp vanilla

1 tsp salt

280 grams (2 cups) coarsely grated zucchini (1-2 medium zucchinis)

120 grams (1 cup) spelt flour

90 grams (3/4 cup) rye flour

63 grams (2/3 cup) cocoa powder

1 tsp baking powder

1 tsp baking soda

175 grams (about 1 cup) bittersweet chocolate, finely chopped

1 Tbs turbinado or Demerara sugar

Preheat the oven to 325. Butter a 9x5-inch loaf pan and line it with parchment paper, so that the long sides hang over the edges to create a sling.

In a large bowl, whisk together the eggs, sugar, oil, vanilla, and salt, until smooth and thick, about 1 minute. Add the grated zucchini and mix with a rubber spatula until just incorporated. Don’t squeeze the liquid out of the zucchini! It helps keep the cake moist.

Sift the flours, cocoa powder, baking powder, and baking soda directly into the bowl, using a fine mesh strainer. (It’s really worth doing the sifting, or you’ll end up with annoying, unpleasant bits of unmixed flour.) Mix with a rubber spatula until no streaks of flour remain, and then gently stir in all but a handful of the chopped chocolate.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan. Sprinkle the remaining chopped chocolate and coarse sugar on top. Bake for 75-90 minutes, until the cake is puffed and a skewer inserted in the center comes out clean. Mine took about 85 minutes, but start checking it at 75. If it doesn’t seem quite done but the top is getting dark, you can cover it with foil for the last 10 minutes of baking. Let cool before lifting it out of the pan to slice.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Yet Another Tasty Grain & Summer Veg Bowl

This is another one of those non-recipes that consists of putting a bunch of vegetables in a bowl with some cheese and mixing. I’ve been eating a lot of meals like this recently, because that’s what August is for.

Cook some bulgar, or use another grain you like. Use 2-3 cups if you’re feeding a few people, or want enough for a few days. Toss the grain of your choosing in a big bowl with two chopped tomatoes, a sliced cumber, a few big handfuls of arugula (or spinach, etc.), a few chopped hard boiled eggs, a few tablespoons each of chopped fresh dill, parsley, and basil (or mint, or cilantro), and some goat cheese. Add a few spoonfuls of pickled onions along with some of their dressing. You have some of those in your fridge, right? If not: slice an onion, toss it with a few glugs of sherry vinegar, a spoonful of honey, and a hefty pinch of salt. Stir and let sit for 20 minutes. Add some olive oil, salt and pepper to taste, a splash of vinegar, and mix well.

The Beat: The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee, read by Lisa Flanagan

This is a novel to luxuriate in. It’s set in Second Empire France, and it’s a sweeping, epic, beautifully plotted tale about Lilliet Berne, a young woman who flees America, becomes a famous opera star, and carries a lot of secrets. It’s not the sort of thing I usually go for, but I’m determined to read everything Chee writes. So far, unsurprisingly, the writing is masterful. I don’t really care what it’s about or what happens. The prose is so sure, the details so careful. I love finding books like this, stories so adeptly told that all I have to do is sit back and let someone who is very good at their job sweep me away.

The Bookshelf

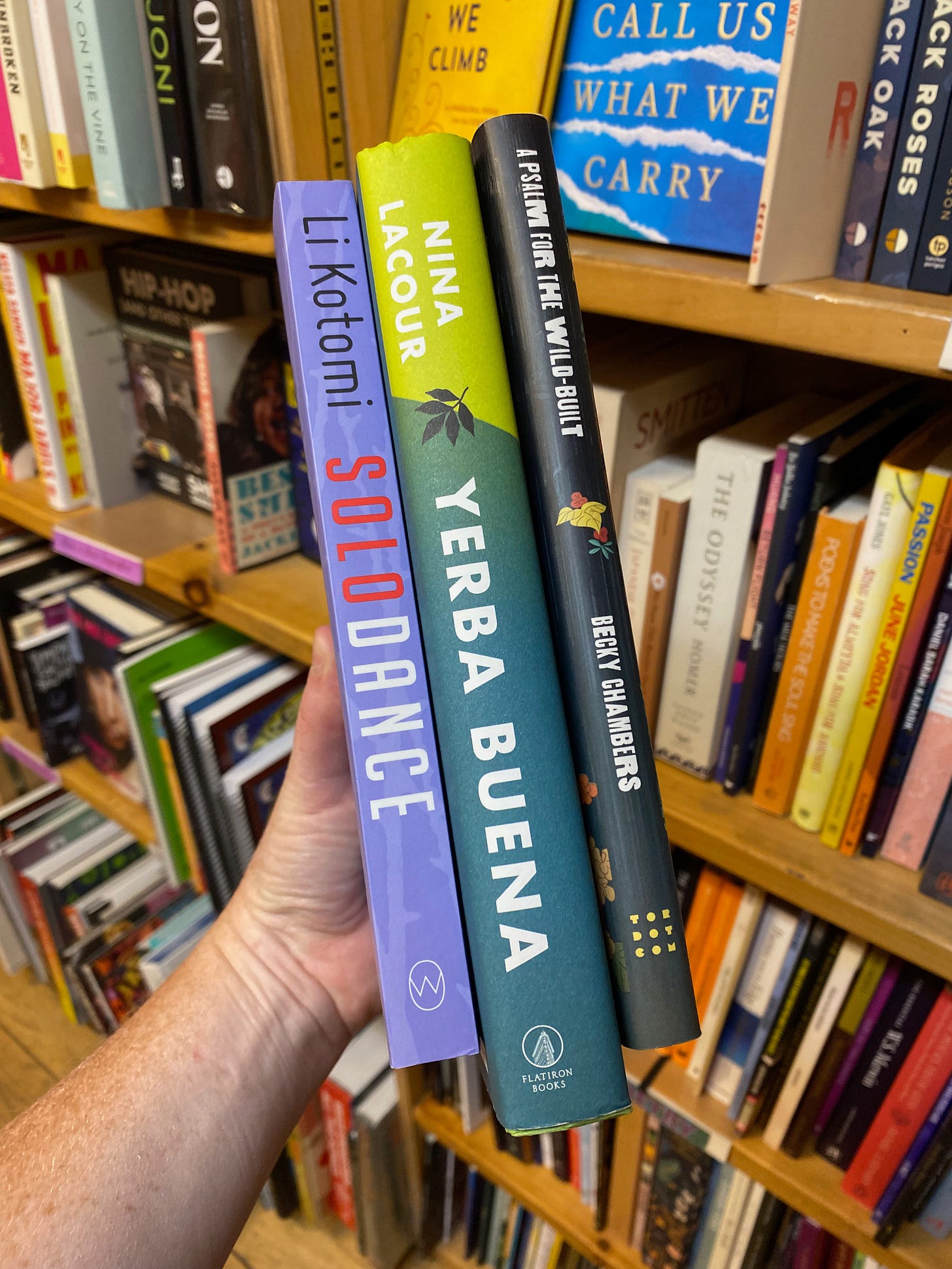

A Picture

I stopped at one of my favorite local indies over the weekend, Everyone’s Books in Brattleboro. I picked up Yerba Buena (one of my favorite books of the year—I needed a physical copy), A Psalm for the Wild-Built (another book I love and have been wanting a copy of), and Solo Dance (queer fiction translated from the Japanese that I’ve been excited about reading for a while).

Bonus Recs: More University Press Books I Love

The Spectral Wilderness by Oliver Bendorf (Kent State University Press) is a gorgeous collection of poems about farming, the natural world, transness. Limbo Beirut by Hilal Chouman, tr. Anna Ziajka Stanton (University of Texas Press) is an interesting novel about the intersecting lives of five different people, set in Beirut in 2008. Blonde Indian by Ernestine Hayes (University of Arizona Press) is a beautiful nonlinear memoir.

The Boost

The latest newsletter from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology included a highlight reel from their 2022 barred owl cam, which is a truly wonderful four minutes of video footage. I’ve also been enjoying their migration dashboard, which collects data about migrating birds across the contiguous United States. You can look up your county to get all sorts of fascinating information about migration patterns, including an estimated total of how many birds were in flight during the night, and a list of likely migrants arriving or departing. An estimated 41,100 birds flew over Franklin County on Tuesday evening!

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I spent most of last Saturday at one of my favorite places, Kilburn Pond. Swimming through all that glorious blue on such a beautiful day—cool and breezy—reminded me why I live here.

Catch you next week, bookish friends!