Greetings, book-chompers and delighters-in-treats. For the past week or so I’ve been watching a pair of downy woodpeckers, an adult male and a juvenile. The juvenile sits in a tree at the edge of my yard. The adult flies down to the feeder, collects some suet, flies back to where the juvenile is perched, feeds it, and then returns for more suet. He made this trip six or seven times while I watched on Saturday, returning again and again to the juvenile’s perch with morsel after tasty morsel.

I spent a lot of time over the weekend watching birds. The woods around my house are loud with calls I can’t yet identify. There’s a pair of white-breasted nuthatches with at least one juvenile, all of whom have been extremely chatty. A hummingbird has been hovering around my porch, though I haven’t been able to get a close look at it yet. The red-winged blackbirds are here. All of this bird activity has brought me a lot of comfort, because it reminds me how wide and mysterious the world truly is. But I’ve also been thinking a lot about those downy woodpeckers. I suppose it’s just what birds do, and reading anything into it is me and my humanness, searching for meaning in the mundane (though still beautiful) routine of biological necessity.

But I am full of humanness, and so I’ve been thinking about all those flights back and forth from the feeder to the tree, the energy that little woodpecker exerts on those flights, his patience, his care, feeding his young directly from his own beak, over and over again, until that fluffy little bird learns how to do it on its own.

The overturn of Roe is not the beginning of the U.S.’s spiral into fascism, and it will not be the end. The only way we are going to survive what’s coming is by taking care of each other, by building strong, beautiful, flexible networks of care and knowledge, shared grief and shared responsibility. This is what Black, Indigenous, and people of color, queer and trans and disabled people, immigrants and working class folks and many others whom the state has deemed “other” have been doing for generations.

I didn’t plan it this way, but this week’s books are fitting, because they are about the things that fuel us. That strange alchemy of memory and lineage and desire and pain that moves us forward. Sometimes fuel is sustenance, the thing that makes life and good work possible. And sometimes fuel eats a person up from the inside. Some of the characters in these novels are fueled by rage that burns clean and bright. Some of them are fueled by too many years of grief, by the warped expectations the world lays on them, by ghosts.

I hope we can all find our good fuel, the long-burning kind, the kind that comes from our deepest wells, and replenishes itself as we use it up.

The Books

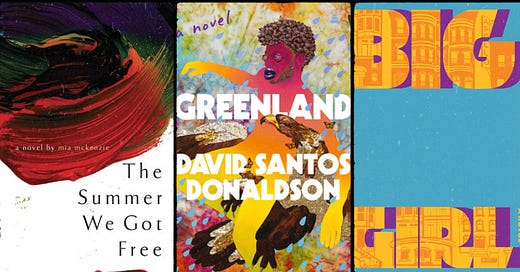

Backlist: The Summer We Got Free by Mia McKenzie (Fiction, 2012)

I loved Skye Falling, and while there are some similar themes here—Black Philadelphia, queerness, trauma—this book is nothing like it. It is rawer and stranger and more ravenous. I read it in two days and now it's on my list of all-time favorite novels. It is the kind of book that builds slowly, but oh, how it builds. Oh what it reveals. Oh how deep it goes, bone deep, ghost deep, city deep, heart deep. Oh how the characters break and sing and triumph and hurt. Oh how the writing slides along, smooth, whole, a gulp of unbearable loss and ferocious joy. Oh how many layers of queerness there are, down down down the queerness goes, intergenerational and silenced, hidden and shame-filled, loud and joyous. Oh how much of this brutal world is in these pages. How much wonder.

It's about the Delaneys, a Black family in Philadelphia, told in alternating timelines, in 1986 and the 1950s. This family has been living with deep grief for a long time. Ava, especially, has been holding this grief in a way that everyone can read in her gestures and her voice: she's not who she once was. The space between who she used to be and who she is now is at the heart of the book. But McKenzie spins the story out in a thousand directions. The POV moves around between Ava, her sister, her parents, her husband, Paul, and Helena, Paul’s sister. When Helena arrives at the family's house one summer, it awakens something in all of them: freedom, reckoning, release.

There are so many fragile webs of connection here. McKenzie’s characters are tied to each other and to places and to history and to the future in infinite complicated ways. Everything—every moment, every person, every memory, every ghost, all the conversations, the meals, the city streets, the church services, all the weeping and silences, every shade of paint Ava uses, each room in the Delaney’s house—is intimately, inexorably linked. This is part of why it’s so outrageously good. McKenzie writes with conviction and beauty, and she illuminates this truth in scene after scene: that nothing is separate, that all the whirling parts of who we are are connected to the whirling parts of those we love, those who have hurt us, those we long to be, those we have betrayed. It is impossible to untangle the threads.

One of the many things I can't stop thinking about is the way McKenzie writes about what fuels each character. They are fueled by shame, self-loathing, grief, wildness, anger, by the desire to be heard and whole, by the need for quiet, by memory, by love, by each other. And the things that fuel them shift and murmur, are opaque and then become clear. Sometimes this fuel is hidden to the characters themselves; sometimes they are acutely aware of it.

We so often think of fuel as life-giving—what makes things move, the sustenance we need to survive. But the fuels that burn under the surface of this book are much more complicated: they are generative and destructive, they hold characters back and propel them forward, they obfuscate and illuminate. It is so gorgeously built.

I can't adequately articulate how deeply this book hooked itself in me. I’m still thinking about the title. On the surface, it’s a succinct description of what happens in the book. But in the fertile underground, it’s so much more than that. There are endless stories in the title alone. I can’t wait to reread it, to unearth even more.

Frontlist: Greenland by David Santos Donaldson (Fiction)

This is a stunning work of fiction that is far too layered and endless to review. It is expansive and propulsive, a human story that I felt in my skin, that I will carry in my heart forever, that I will never come to the end of. It’s one of those rare and perfect books that reminds me of the pure and absolute joy of being a reader, even as it speaks to the complexity and impossibility and weight of being a human on this wild, broken planet.

Greenland is so many things: a novel within a novel; a biting, darkly funny contemporary about being Black and queer in America (and the UK); a ghost story; a surreal travelogue; a visceral exploration of writing and storytelling. It’s about the lingering violence of colonization in the US and UK and Caribbean. It’s also a brilliant and hilarious book about the all-consuming desire for recognition and how that warps (and fuels and guides and changes) a person. It is a moving drama about a dissolving marriage and a gorgeous, rageful heartbeat pounding the undeniable truth about the US: everything is always, has always, been about race.

Kip is a Black gay writer who has locked himself in his basement to finish his historical novel about Mohammed el Adl, the Black Egyptian lover of E.M. Forster. The story begins in this confined space but eventually vaults out of it—literally and metaphorically. Kip is such a mess, and he’s also an incredible observer, both of himself and the world. There are layers upon philosophical layers in this novel, and somehow, it’s also a page turner. I couldn’t listen to it fast enough and I didn’t want it to end. As Kip journeys, so does the novel. It begins as the account of a writer desperate for success, and becomes a powerful story about the places we create healing.

Throughout the whole novel, but especially in a scene near the end that will haunt me for the rest of my life, the queer present reaches out to touch the queer past. It is release and relief. Grief and recognition. Kip and Mohammed meet in some place beyond time, a portal built of work and possibility and yearning, a geography shaped by their co-creation of a world where they can be their queer Black selves, free and unfettered.

This moment, and the entire book, which is really a conversation between the queer past and the queer present, is not simple or linear. Kip and Mohammed, though separated by a hundred years, share so many of the same experiences. This is one of the things I love about the way time works in this book: Donaldson acknowledges the progress we’ve made and the progress we haven’t made. Time collapses because we are always in process, in progress, in flux. History doesn’t move forward in an easy line from bondage to liberation. There is no destination. There is always a queer now, held sacred by future possibilities, made possible by queer ancestors. The queer present makes the queer past possible. Kip and Mohammed make each other possible.The stories we tell make our lives possible.

The way that self and voice blend and blur in this book is so moving; I can hardly write about it without crying. Mohammed and Kip speak to each other and become each other; they create each other. Isn’t this what storytelling is? Isn’t it a way of teasing out what separates us and what doesn’t, a way of expanding and collapsing the space between reader and writer, self and other, after and before?

Kip is such an astonishingly complicated character; from my vantage point, outside of so much of his experience, I can only scratch the surface of the things that fuel him. He’s fueled by his need to be published. Beneath that: his need to be seen by a world that so often refuses to see him. Beneath that: a desire to be known, truly. To know himself. And beneath that, and beneath that, and beneath that. What are any of us living for?

Kip begins with what’s easy: he locks himself in a basement so he can write a book that might get him the success he longs for. But he keeps writing, and he keeps writing, and he writes his way into what’s underneath, and what’s underneath that. Where does his rage come from, where do his wants come from, where does his tenderness live, where’s the beginning of the engine that drives him, where does he start? He writes and he writes, and by the time he finally meets the past—himself?—in the most unexpected of places, he’s still striving and sad, he’s still lost, he’s still unfinished. But by then it doesn't matter so much what lies at the core of him. What matters is the space he’s made for himself to step into.

If there is healing in this world, if there is healing in this book, Kip finds it in the act of storytelling, in the act of world-building, in the endless conversation across time and space and sameness and difference that begins when he puts his fingers to his keyboard, and begins again when he opens his mouth and lets his whole messy self come roaring out.

Upcoming: Big Girl by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan (Fiction, Liveright, July 12)

This is a deeply interior, breathless, and often excruciating coming-of-age, coming-into-self novel about a fat Black girl in 1980s and 1990s Harlem. Malaya’s world, for most of her childhood and teen years, revolves around her weight, and how the world views her because of her weight. Her mother and grandmother see her fatness as an aberration and a problem. Her mother takes her to Weight Watchers meetings as a young girl, and she learns quickly to count calories, ignore her desires and treat her body as something to be tamed and conquered.

All of this intense pressure to be thin, to conform to normative white beauty standards, to punish herself instead of celebrating herself, is made even louder by the racism and alienation she faces as a Black girl at a predominately white prep school.

She finds pockets of joy and comfort in small moments—with her father, with her best friends, Shaniece, in the music of rap artists like Biggie Smalls. Sullivan renders these moments of tenderness with the same care and detail she uses to describe the rest of Malaya’s life. It’s the intensity of Malaya’s narration, the relentless presentness of it, that makes this book so powerful. Sullivan never strays into another POV, never wanders out of Malaya’s current understanding of herself. It’s not a wide-angle view. Malaya is not looking back at events from some future date; she relates them as they unfold. This means that for long stretches, we are as stuck as Malaya is, deep in the muck of aloneness and loss. It also means that we feel the earth-shattering power of her slow but certain transformation, her eventual embrace of her fat Black young womanhood.

There is so much that fuels Malaya. Her desire to be seen and loved. Hunger. Her mother’s expectations. She’s fueled by the way other people see her, by the way the world sees her, by the male gaze, the white gaze, the insistent chorus of voices telling her to be smaller, desire less. There is so much trash fuel in Malaya’s life. There’s so much fuel that doesn’t fill her up, that empties her out instead. The world is full of fuel like this—body shame and fatphobia and racism and homophobia and the hundred thousand little violences they inflict on bodies like Malaya’s every day.

It’s not Malaya’s only fuel, though. She’s also fueled by a deep sense of herself, by an innate belief, often buried, that she isn’t wrong, that her body isn’t broken. It’s not until she experiences her first devastating loss that she begins to listen to this part of herself. In her grief, she slowly starts to let the good fuel guide her days. She lets her hunger out. She lets her body out. Finally, she takes up space.

I do want to mention that Malaya ends up losing weigh, though she doesn’t do it on purpose. There’s no dieting (at least not at the end—it is addressed earlier in the novel), and her weight loss isn’t portrayed as the thing that heals her. She finds joy in her fatness and loses weight afterwards, as she goes about her life. This is not an easy book to read, but throughout, Sullivan writes about bodies and fatness and internalized fatphobia and familial trauma and with a lot of nuance and compassion.

And yes, this book is queer! Quietly, beautifully queer. There are a few truly lovely moments of queer love and connection. It’s in these moments, in fact, that Malaya first glimpses what it’s like to be held and seen by someone else, to exist safely in her body, to find pleasure in her body, to be vulnerable with another human. Queer desire creates possibility in Malaya’s life.

It’s out July 12th, and you can preorder it here.

The Bake

The great thing about having a go-to scone recipe is that you can transform it into a hundred different kinds of scones. I was craving something salty-sweet this weekend, so I decided to put one of my favorite pizza toppings into a scone: figs, bacon, fresh mozzarella, and rosemary. I was not disappointed.

Bacon, Fig & Mozzarella Scones

Makes 8 scones

Ingredients

255 grams (2 cups) all-purpose flour

1 Tbs sugar

1/2 tsp salt

1 tsp freshly ground black pepper

1 Tbs baking powder

1 stick (8 Tbs, 113 grams) cold unsalted butter, cubed

1 Tbs chopped fresh herbs (whatever you like best)

4 slices bacon, cooked and chopped into small pieces

5 figs, chopped into small pieces

4 ounces fresh mozzarella, cubed

1 cup (105 grams) buttermilk

Preheat the oven to 400. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper or a silicone baking mat.

In a large bowl, combine the flour, sugar, salt, pepper, and baking powder. Add the butter and use your fingertips to mix it into the dough until only pea-sized lumps remain. Mix in the herbs, bacon, figs, and mozzarella. Make a well in the center and add the buttermilk. Stir just until the dough comes together. If it seems too wet or too dry, add a little more flour or buttermilk.

Turn out the dough onto the center of the baking sheet and pat it into a rough oval. Cut the oval into eight equal pieces. Bake for 20-25 minutes, until the scones are golden brown and puffed. Recut them as soon as they come out of the oven, but wait until they’re slightly cooled to separate.

The Bowl and The Beat

The Bowl: Herby Zucchini Pasta Bake

This dish is adapted from Smitten Kitchen, and it’s example of why I love cookbooks so much. I used Deb’s exact proportions to make the sauce, but beyond that, I didn’t measure a thing, subbed ingredients for other ones, left some things out, and added others in. I didn’t really need the recipe, but I needed the inspiration it gave me.

Cook your pasta, any shape, maybe 2/3 of a package. Drain and set aside. Slice 3-4 summer squash into thin rounds. Heat some olive oil in a large oven-proof pan. Cook the squash until it starts to brown. Transfer to a bowl and sprinkle with salt and pepper.

Add 3 tablespoons butter to the pan, along with the sliced white parts of a bunch of scallions and 2-3 pressed garlic cloves. Add 3 tablespoons of flour, stir to dissolve, and then add 1 1/2 cups milk, slowly, a splash at a time, stirring after each addition. Let sauce simmer for 2-3 minutes, stirring; it will thicken. Remove from the heat and add salt, pepper, a big handful of chopped parsley, the sliced green parts from the scallions, and 1-2 tablespoons chopped fresh herbs. I used mint, rosemary, thyme, and basil.

To the pot with the sauce, add the summer squash, pasta, about 4 ounces of cubed fresh mozzarella, 1-2 tablespoons of mustard, and at least 3/4 cup grated Parmesan. Mix well. Sprinkle more grated Parmesan on top. Bake at 400 for about 30 minutes. It freezes well, but I happily ate it for lunch for a week.

The Beat: The Companion by EE Ottoman, read by Kdin Jenzen

I’m still listening to the final book in the Broken Earth trilogy, but I’m also listening to this lovely historical romance! I’ve started listening to romance before falling asleep, and while it takes me a long time to get through a book, it’s been a game-changer for my sleep cycle. The audio of this is only available through Scribd, but I highly recommend the book. It’s a romance between two trans women and a trans man, set in upstate New York in the 1940s. So far it is very gentle.

The Bookshelf

A Picture

My porch is my new favorite weekend morning reading spot.

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I made a list of some of my favorite queer short story collections from the past few years.

Bonus Recs about What Fuels Us

Rain: A Natural and Cultural History by Cynthia Barnett is a wonderful book about one of the things that fuels us, literally. No Ashes in the Fire by Darnell Moore and When They Call You a Terrorist by Patrisse Cullors are two memoirs about what fuels activism and radical organizing.

The Boost

This is the list I made for myself on Sunday night, after an internet-free weekend eating ice cream, watching birds, and swimming in the river:

Find your local abortion fund. Mine is the Abortion Rights Fund of Western Mass. Reach out to see what they need (besides my monthly donation). Be patient about it.

That’s it, that’s the list. It’s not simple. But the networks exist. Abortion funds aren’t the only ones. Our work is to be a part of them.

Some recent writings (of many) on this I’ve found helpful: Anne Helen Petersen’s “Your State Will Not Save You” and Dr. Ayesha Khan’s words on solidarity and organizing.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: Hills, clouds, pup.

Catch you next week, bookish friends!

Thank you so much for writing this newsletter, Laura! Every single book you mentioned is going on my tbr and I love hearing about your bird neighbors. I want to learn more about more birds and practice noticing them in my surroundings so this was very inspiring. Your newsletter is a balm and a source of fuel. Thank you!