Volume 3, No. 38: It Hurts, It Hurts, It Hurts, It Sings + Two Beloved Fall Cakes

Greetings, book and treat people! It feels like fall might finally be here. I’m still swimming every day, but the lake is getting cold. All that sweet, chilly water rushing over my skin is the most glorious feeling in the world. I also spent a long afternoon last weekend reading under a blanket while sipping mulled cider and eating pear cake. Also: sunrise walks. Docks are back! Nights in the 40s, i.e. sleeping weather! My time is here. My time is coming.

I’m also being serenaded by barred owls every night. Their calls are amazing. I have yet to see one, but the other night it sounded like there were at least six of them, calling and hooting and singing in the trees just beyond my porch. There were waves and waves of overlapping songs—for a minute I wasn’t sure if it was just owls or owls and coyotes together. Either way, it’s gorgeous and special.

This week’s books hurt my heart. They hurt my heart but they also sang to me—tender, alive, here. Being a human—it hurts, it hurts, it hurts so much, it sings. It seems impossible, but here we are. Hurting and singing.

Side note: I try to share reviews here before I post them on Instagram, but this doesn’t always happen. If you follow me there, you should know that newsletter reviews are always expanded! I used to think I’d somehow failed if I reviewed a book here I’d already reviewed or partially reviewed elsewhere, but guess what: I’m a human doing my best. I’m not failing. I’m just shouting about books I love in more than one place.

The Books

Family Meal by Bryan Washington (Fiction, Riverhead, October 10th)

This book destroyed me and then wove me back together. It hurts. But along with all that hurt is a gorgeous, healing story about friendship and family and people taking care of each other, which is the only thing, maybe, the only important thing. People taking care of each other even though they’ve wronged each other. People taking care of each other even though they’re mad at each other. People taking care of each other after years of distance and separation. People taking care of each other and not always doing a very good job of it, but trying anyway. People taking care of each other even though they don’t always know each other, not really. People taking care of each other despite, despite, despite.

The novel follows Cam, who moves back home to Houston after the sudden death of his boyfriend Kai. He reconnects with his childhood best friend TJ, with whom he fell out of touch when he left home. The first section, told from Cam’s POV, is basically perfect. Cam is not okay. He’s deep in grief and deep in a self-destructive spiral that keeps spinning and spinning and spinning. He finds a job in a struggling gay bar and moves in with the owner and his husband. He hangs out with TJ but he doesn’t really let TJ see him. He spends a lot of time talking with Kai’s ghost. It’s hard to describe how painful and breathless it is to be inside Cam’s head for these pages—to know him and his pain, to see the things he’s not allowing himself to see. The death of his boyfriend looms; Cam’s life afterward looms; all of his complicated, unresolved feelings about TJ, Houston, and his childhood loom.

It’s so intense, and it’s also full of ordinary life. Washington writes beautiful scenes. He’s extremely good at writing about place and food and sex. This makes the book feel small in intimate ways, even though its scope is nearly infinite. Somehow, Washington puts the whole world into his writing, the world his characters move through every day, and so there’s racism and violence and tenderness, hookups and therapy, meltdowns and mistakes, fights and escapes, easy conversations and hard ones, lighthearted banter and loneliness. There are dozens and dozens of meals.

The second half of the book is told from partly from TJ’s POV and partly from Kai’s. At first I didn’t think Washington would be able to pull off this abrupt switch, but he does. The way he uses POV is brilliant, because this is a novel about what people are willing to give to each other even when they don’t know the whole story. The three characters are connected in messy, complicated ways. Their lives are deeply threaded together. But they also hold each other apart from each other. The story happens in the spaces that grief makes, in the gulfs that memory and shared history and friendship and love can’t necessarily cross.

This novel hurts in a million ways but it heals in a million ways, too. The story happens in the crossing. Cam and TJ and Kai are all trying to cross those impossible gulfs—history, hurt, misunderstanding, fear, the world and its violences—toward each other. Sometimes they fall flat on their faces and sometimes they fly. Along the way there is a lot of muck and tears and laughter and comfort. And the way never ends. The crossing, the trying, the reaching out toward, despite how hard and how small it all sometimes feels—it’s endless. I can’t wait to read this book again.

Carry by Toni Jensen (Memoir, 2021)

Oh, this book hurt. Hurt my heart, hurt my brain, hurt on my skin as I let (tried to let) Jensen’s words sink in, hurt because it’s so beautiful, the sentences and the music and the stories, and it hurts, this beauty made of horror and violence. It’s a memoir about gun violence, sexual violence, abuse, survival, motherhood, Indigeneity, birds, landscape, belonging and unbelonging, language, whiteness and its weapons, history and what happens when we ignore it, mythologize it, sanitize it.

I can’t get this one line out of my head, especially—I’ve been turning it over and over for weeks: “It’s okay, I’ve learned, to love the things that make you, even if they also are the things that unmake you.” I’ve been working through what Jensen means here, and I doubt I’ve come to the bottom of it, but what has stayed with me, in the days since I finished this book, is how deeply Jensen looks at what she writes about, whether it’s her own childhood, her abusive father, the conditions of white supremacy that lead to abuse and violence, a neighborhood in Pittsburgh, a college classroom. She looks at all of these things in dozens of ways, looks at where they intersect and where they clash. She looks at the gifts she’s been given by the people and places in her life and the violences she’s survived from the people and places in her life. Her permission to love what makes you, even if it also unmakes you, I think, is permission to love in the midst of, in spite of, with. “How many ways do we carve ourselves up and portion out our parts, our bodies for other people’s comfort?” she asks. And then, in the permission she gives herself, in the writing of this book, she refuses to portion and split.

Looking so closely is one way of deeply tangling everything together. Jensen cannot write about fracking without writing about the land—whose it is, what has been done to it, what it remembers. She cannot write about teaching without writing about racism, cannot write about her father without writing about guns, cannot write about abuse without writing about history, cannot writing about motherhood without writing about childhood, cannot write about being Métis without writing about language.

Perhaps this sounds vague, but the book is anything but: it’s deeply specific and personal, but what is personal? Jensen makes it clear that to live in a body (“in this, our America”), any body, but especially a body that is woman, nonwhite, a body that troubles lines and categories—is not only personal. No one belongs only to themselves. We cannot untangle what tangles us without looking at it.

Because these times and those times and all times are connected through land and bodies and water.”

This book is devastating, both sure and curious, poetic, and gorgeous. It’s some of the best writing about place I’ve read in a while. It hurts, and it’s a song.

In Memoriam by Alice Winn (Historical Fiction, 2023)

A boy is in love with his best friend but he’s afraid to say so because he’s not supposed to love another boy, so he enlists in the army. It’s easier to imagine dying for an empire than it is to imagine letting his body want what it wants. He doesn’t buy the nationalistic propaganda his friends are lapping up, but he lets it swallow him anyway. It is easier to be swallowed by an empire than to speak a small, true thing. This is one of the ways empire swells: it convinces even its chosen few to feed themselves to it.

The boy’s best friend follows the boy to war because he is seventeen and dramatic and poetic and pining and and also in love, though he’s too afraid to say so. He follows the boy he loves to war because the empire says, “heroic”, says “glory”, says “yours”, and so he goes, because he is seventeen and dramatic and rich and used to getting what he wants. He doesn’t understand what the empire means when it says “heroic” and “glory.” He learns.

Two boys go to war, and the empire tells them that now they are men. Two boys who learned easily and early what men are not allowed, and so know not to cry, or crack, or speak their love—try. These boys at war write letters to the mothers of other boys, explaining how their sons were killed in action, died glorious deaths. Watch how empire eats language. Watch the way it turns the language of wonder into muck. Watch the boys try to swallow the lies they write. Watch them go down easy, come up red.

A boy goes to war and breaks. Put him on any continent, in any decade. Put a boy who went to war, where he learned to be the kind of man the empire told him he had to be, in a room with a girl. Watch her break. Watch him break her. Watch him, broken, break her. An empire is always hungry. It eats and eats and calls it conquering, and then, still hungry, it eats the ones it ordered to do the killing.

A woman writes a book about a war, a war many books have been written about. It is a particular book about two particular people—rich white English boys—and the particular ways empire tries to destroy them while they try to save each other. It is not about the girl in the room, the women lost, the other wars, the children dead without an in memoriam. The book is not about these things, but they are what the woman reading the book (me) is thinking about as she reads. The snares of empire, tripped, tripped again, going off endlessly, all over the world. The woman reading the book (me) knows that empires are not monsters. They are made of people. It’s people, all the way down. We do this to each other.

Two broken boys survive a war. Two broken boys find their way back to each other. Put them alone in a room. Watch them reaching across caverns. Somehow, still, despite, despite, despite—watch them touch each other’s new and broken faces. Watch them be witness to each other’s breaking. Watch them make something sweet in the breakage. It’s people, all the way down. We do this to each other.

A boy grows up in a war and carries the war inside him forever. The boy he loves grows up in a war and carries it too. The empire spits them out but doesn’t lose its teeth. The boys survive but lose bits of themselves. The empire sharpens its claws. The boys, somehow, still, despite, despite, despite, fold their claws—the claws the empire told them were glory—into tears, from which, maybe, just maybe, something else will sprout.

The Bake

Two Beloved Fall Cakes

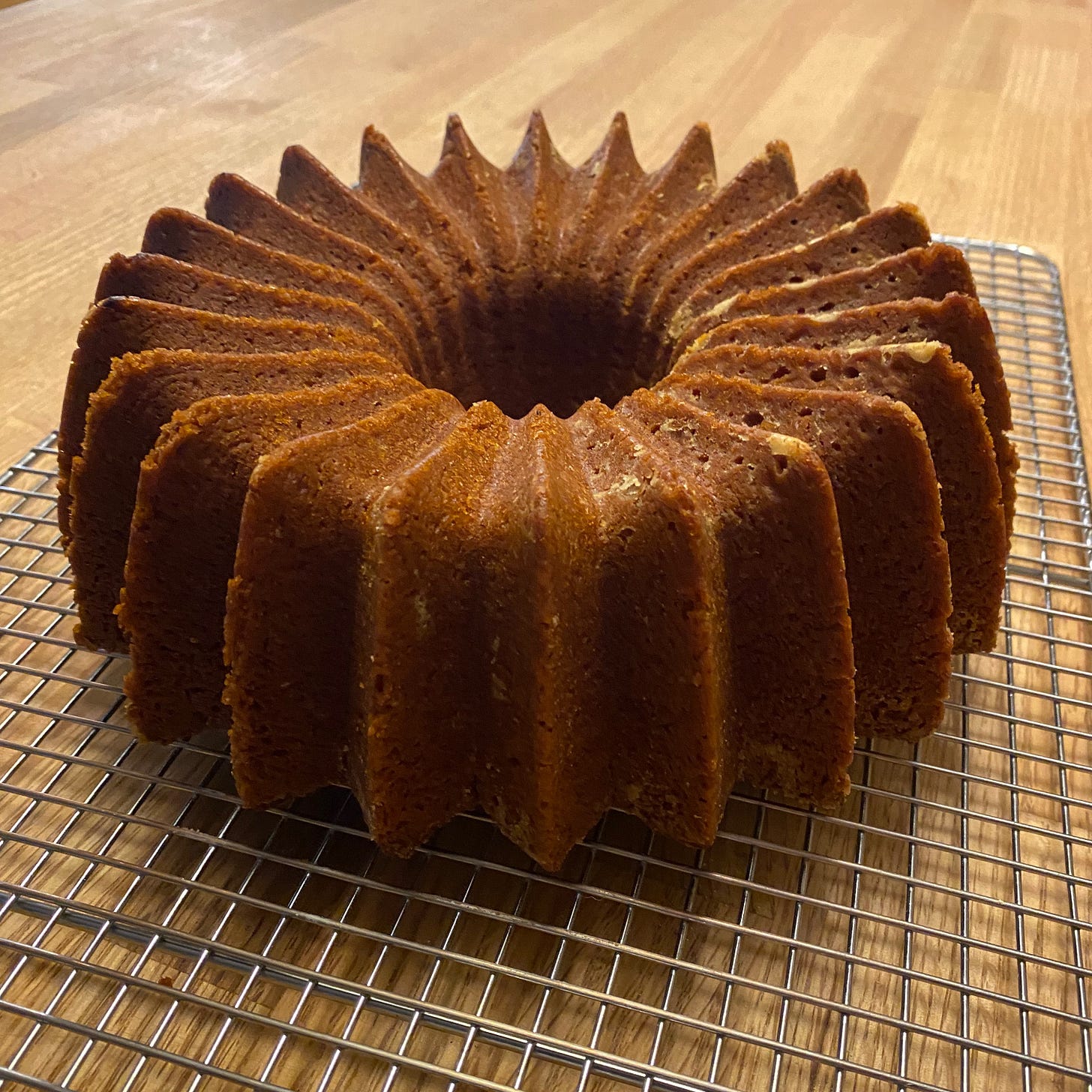

I’m all over the place with baking. I’ve been checking cookbooks out of the library, getting excited about them, and returning them. Maybe the return of Bake Off (this week!) will reenergize me. In the meantime, I’ve made two amazing cakes this month that I want to share with you. One is a go-to Rosh Hashanah cake and the other is a go-to everyday fall cake. They both happen to be Melissa Clark recipes (via NYT Cooking—apologies for the paywalled links) and they are both supremely delicious.

Red Wine and Honey Cake

This cake is so good that even without the accompanying plums (I didn’t have any) or any kind of glaze (I didn’t feel like it), it’s still basically perfect. It actually tastes like honey (don’t get me started on honey cakes that don’t), the spice mix is divine, and the wine adds a lovely depth. No notes.

Pear Crumb Cake

I made this cake last fall and forgot about it, and then I bought some pears and found it again when I was looking up recipes. You sauté the pears in butter and honey and then add spices and lemon juice (or cider). You make a buttery crumb with brown sugar and cinnamon. Then you make a simple, elegant, vanilla sponge and layer the pears and crumb on top. The mix of textures is perfect: light, airy cake; gooey pears; and crunchy, caramelized topping. It’s one of those cakes that seems like it shouldn’t be as wildly good as it is.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: Fall Tuna Melts

I forget tuna exists most of the time and then I remember and buy some and make a tun melt and I am so happy. I don’t know why tuna melts are so good. They just are. This one is Peak Fall—apples, fennel, parsley, scallions—but of course you can make your tuna salad however you want.

Open some tuna. I used three cans so I could have tuna melts for lunch all week, so if you’re using just one can, reduce the quantities of everything else accordingly. Drain and dump the tuna into a bowl. Add a few big spoonfuls of yogurt, 1-2 tablespoons of mustard, a few glugs of olive oil, the juice of one lemon, and salt and pepper. Mix well and taste. Add more yogurt/mustard/oil/lemon juice until the mixture has a texture and flavor you like. Dice an apple and add it. Thinly slice 1/4 of a large fennel bulb and add that. Mince a big handful of parsley and toss it in. Thinly slice two scallions—into the bowl they go. Capers and celery are nice, too. Mix it all up and taste again. When it’s to your liking, pile some tuna salad onto your favorite bread, top with sliced cheddar, and broil until golden. If you have tomato soup, you’re extra lucky.

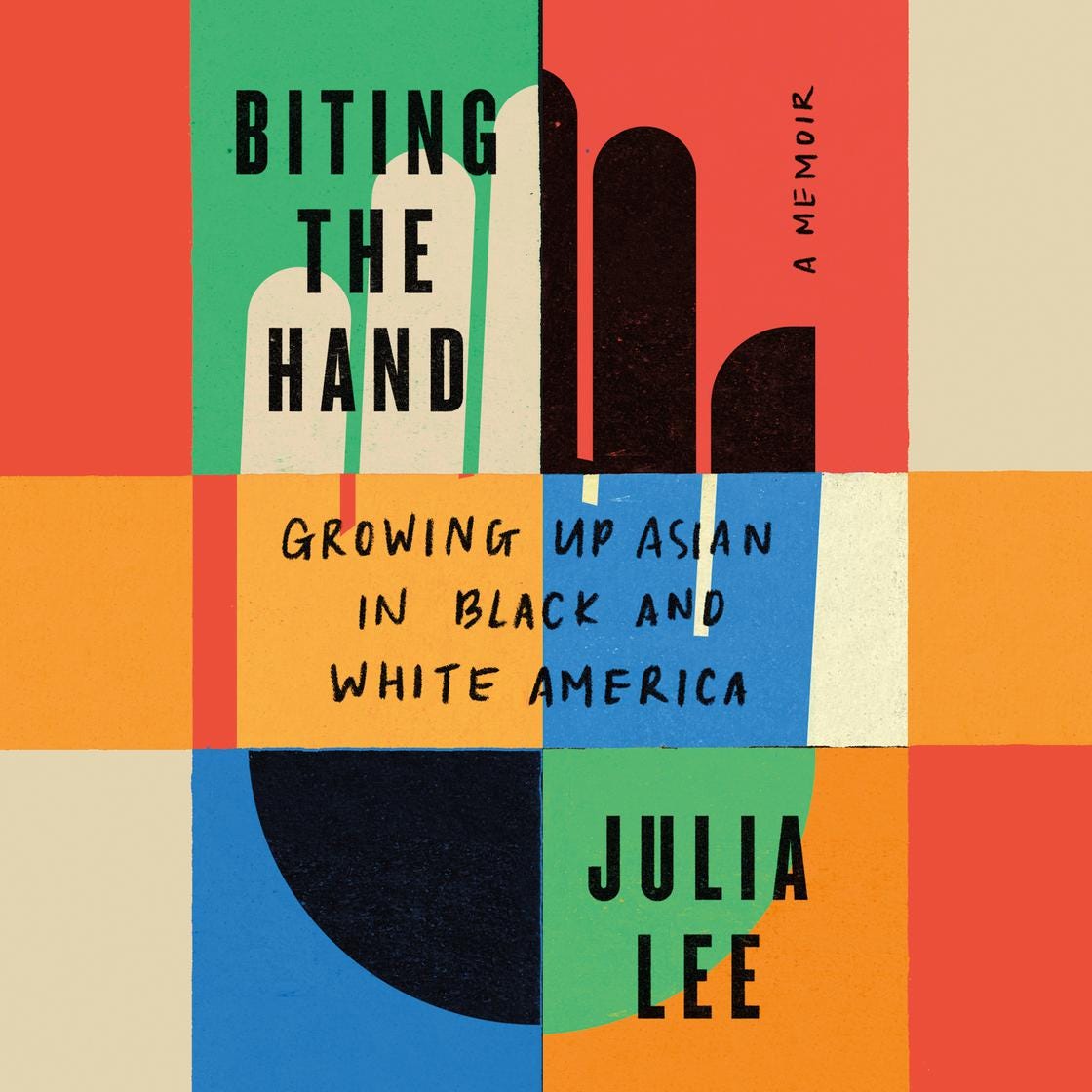

The Beat: Biting the Hand written and read by Julia Lee

This is a memoir and also a scathing critique—expose? uncovering?—of white supremacy and white supremacist culture and how its violence affects the lives of Asian Americas. I’m having trouble coming up with the right word for this book, a word with the right amount of heft, intellectual rigor, and seething anger. She writes about so much and goes into a lot of detail and doesn’t try to make any of it palatable: academic racism, the fetishization of Asian women, the 1992 LA uprising, the racial imagination and the shame it engenders, mental illness and how it intersects with racism. I really can’t say enough about the anger in this book. Lee’s rage is incandescent and powerful and she puts that into her narration, too, which is so emotional. Anger belongs in a book like this. I’m about 2/3 of the way through and highly recommend it. I also recommend reading Kristin’s review and Traci’s review .

The Bookshelf

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I rounded up some of the best books by trans women and transfeminine authors that have come out this year. I also wrote a love letter to Bookstagram and the incredible scholarship I encounter there. Make a note: nuance on the internet isn’t dead. I wrote about family sagas with creative structures for AudioFile. My review of Land of Milk and Honey is up on BookPage.

A Taste of the Commonplace

I’ve spent the past few weeks updating my commonplace book, because I got woefully behind this summer. I’m mostly caught up now, and I’ve also (finally!) learned how to filter all the passages I’ve saved by tags. I tag abundantly, so it’s pretty awesome—I can sort all my saved quotes by themes like “ocean”, “liberation”, “sex”, “exile”, “queer history”, “memory”, “longing”, “birds”, “diaspora”—you get the idea. So I thought I’d pick a tag each week, either related to the newsletter’s theme or something happening in the world or my life, and share a passage from a book I love.

This week’s theme is fall. This poem is from Victoria Chang’s incredible collection The Trees Witness Everything.

In the Doorway The fiftieth fall is finally here. Have you counted the number of leaves that have brushed your face? The number of times fall checkmated summer? If you think fall is made of dying, you are wrong, it is made up of the future.

Please let me know if sharing quotes like this is something you enjoy!

Queer Your Year

It’s time for the September raffle! This month’s prize is a Mystery Queer Book Bundle! You’ll get five queer books: a mix of ARCs, paperbacks, and hardcovers in a variety of genres: nonfiction, poetry, fiction, science fiction, and a speculative novel. Check out all the details here!

You can submit your game card and find all the details here. You have until October 1 to submit. The winning prompts this month are: 3, 5, 6, 12, 29, 31, 33, and 42.

As always, don’t forget about the super fun prize packs! Everyone who submits a game card gets one, and they ship internationally.

The Boost

There are a few exciting books out this week that I want to tell you about:

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: This is a truly extraordinary work. It left me breathless.

Love and Money, Sex and Death by McKenzie Wark: Honestly this is one of the best memoirs I’ve read this year! It’s a series of letters to past lovers, family members, and versions of Wark herself. It’s about transness, writing and making art, relationships, change.

Dry Land by B. Pladek: I’m only 100 pages into this but it’s a historical novel set in 1917 about a queer forester who loves the Wisconsin woods with his whole being. When he suddenly develops the power to grow plants with his hands, he dreams of rewilding the landscape he adores. The writing is lovely and quiet and there is so much incredible nature writing.

B. Pladek, the author of Dry Land, also made a reading list for Electric Lic of historical novels by 20th century queer writers. Did I scream when I saw it? I did. Did I immediately save every book listed on my library’s website? I did. Have I mentioned lately how much I love 20th century queer lit? Well, now I have.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I’ve been reveling in sunrise walks lately.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! I have no idea what next week’s essay will be about, but if you want to read it, you can subscribe here.