Greetings, book and treat people! I applied for a job I really wanted a few weeks ago and yesterday I found out I didn’t get it. This happens all the time. It’s a small and common occurrence. It was still a disappointment. I had a trash day. I didn’t get much done and slept terribly. This morning I woke up late to a grey and cloudy morning. I drove to the lake, and on the drive, it started raining. I thought I might be the only one at the lake, but when I got there, I saw the group of older women who swim every morning already far out, their heads bobbing in the water. I dove in. The water was silky; the rain gentle but steady; the hills around the lake shrouded in mist. I drove home and took a hot shower. I am eating cake for breakfast.

This year has been extremely hard, but I have put my body into a body of water (river or lake) at least once every day since August 11. That’s 34 days. So, as is often the case, I am exhausted, and I am endlessly grateful.

This week’s books play with silence and empty space. They are about what’s between—the spaces between the words, the years between the scenes—and about what’s left unsaid—the conversations not spoken, the words withheld. They are all very beautiful.

The Books

Glassworks by Olivia Wolfang-Smith (Fiction, 2023)

I love books that tell stories through silence. I especially love novels that do this, novels where what the characters don’t say to each other is the main event. There is something so compelling about this kind of structure. We are so close to our own lives, and often this makes our own lives hard for us to see. It also makes it hard to see into the truths of other people’s lives. This book lives in the center of that tension. It’s about people who don’t always see themselves, and don’t always see each other, and so they circle each other, they keep missing each other, they speak over each other, they break each other.

It’s also a queer family saga (and you know how much I love those). The generations—what gets passed down from one to the next, how they move—are deeply queer. In every generation, the characters defy expectations, twist their lives into unexpected shapes. There’s a kind of queer inheritance that moves through time, often zigzagging, but always traceable, from generation to generation. I was continually amazed by Wolfgang-Smith’s careful choices, the way she uses such a simple structure to tell such a complex story.

The novel takes place over roughly one hundred years, but it’s told in four distinct sections. In 1910, a Boston heiress with an abusive husband falls in love with a Bohemian glassblower and naturalist. In the 1930s, her twenty-something son takes a job as an apprentice at a glassworks studio, even what he really wants is to go to seminary and become a priest (to the dismay of his radical, atheist parents). In the 1980s, his child, a middle-aged queer window washer, gets tangled up in an intense relationship with a rising Broadway star. In 2015, a grieving twenty-something struggles to understand the family secrets her mother has kept close her whole life.

We see each of these characters in pivotal moments, in the midst of turmoil, standing at the edge of dangerous precipices. There is a relentless momentum to each section—they feel like novellas—and then silence. The effect is startling. As readers, we see so much that the characters don’t. At heart, this is a novel about the spaces between parents and children, about silence and how it festers, about what happens when you do not speak, how not speaking distorts relationships, and sometimes time, how it reverberates through years and years.

Characters make startlingly bad decisions. They are often reckless and careless. They rarely understand the people in their lives. Parents are illegible to children and children are mysteries to their parents. All the stories, all the histories, all the sorrows and losses and little cuts and strange coincidences and trauma and accomplishment—everything that underpins their lives, that guides their actions, it’s all right there, in the empty spaces between the sections. It’s all right there, but none of it is spoken. It’s masterfully done.

I didn’t love the ending as much as I loved the rest of the book, but it hardly matters. I’ve been thinking about this one since I finished it. It asks so many messy questions about inheritance, about what gets passed down and what doesn’t, about what is lost, especially when families branch and shift in queer directions, about what we are given by our elders and ancestors, and what we take.

I Will Greet the Sun Again by Khashayar J. Khabushani (Fiction, 2023)

I am a little bit obsessed with scenes. I will not say something trite like “they are the building blocks of fiction”, because that’s way too narrow a definition of fiction and the many ways it’s built. But I love a good scene. Good scenes give me shivers and make my heart beat faster.

This quiet, beautiful, heartbreaking book is a collection of good scenes, one stacked on top of the next. There’s very little exposition. There’s not even much reflection, despite the first person POV. It’s scene after scene after scene, intimate, visceral, immediate. Set in LA and Iran in the 1990s and early 2000s, it’s a coming-of-age story about K, a queer Iranian American kid, the youngest of three brothers. His childhood and teenage years are marked by heartache, grief, and violence. His father is physically and sexually abusive, and becomes even more so during a brief and sudden trip back to Iran. There are scenes of rape and physical violence that are very hard to read.

K’s life is also defined by the deep bond he shares with his brothers—afternoons spent on the basketball court, gentle, loving teasing, the endless tiny ways they protect and care for each other. When I say this book is quiet I mean that yes, it’s about childhood sexual abuse, but it’s also about the sweet softness of teenage crushes and first love, about brotherly in-jokes and summer magic, about falling in love with books, about dreaming big, about growing up and into yourself, and wanting—even after living through the worst.

It’s the scenes that make this novel so extraordinary. They are exquisite. Khabushani’s prose so detailed, so exact. Every scene is so vividly rendered—the scents, the colors, the textures, the sounds. Every scene, also, has its own weight. The scenes of violence do not feel more weighted than the scenes of tenderness. Everything that happens matters, and Khabushani gives it all such thoughtful consideration. Nothing is dramatized or sensational. And though K’s first person narration is wry and observant, it’s also unflinchingly present. He’s narrating from somewhere in the future, but the scenes are grounded in the body, in right now.

The other remarkable thing is the way time moves. Because the book is built almost entirely of scenes, time moves quickly. Sometimes a year goes by in a page. Khabushani jumps from scene to scene, moving from important moment to important moment, leaving the rest unwritten. There is something about this combination of empty space and visceral scene that I’m still trying to untangle, but it’s why I can’t stop thinking about this book. It felt a little bit like an extended prose poem; it cuts to the center and stays there.

There is so much more here about immigrant families and the ways that violence and toxic masculinity move through generations, about racism post-9/11 and the particular ways in which queer kids are often isolated, about food and brotherhood and hope. The ending is poignant and beautiful. I highly recommend the audiobook as well.

Things I Have Withheld by Kei Miller (Essays, 2021)

Kiki, one of my favorite people on Bookstagram (and the person who inspired me to read Kei Miller), wrote this in a recent review: “The more I re-read the more I am tempted to conclude that I haven't started to actually read a book until the second time around.” I’ve been rereading a lot recently, so this sentence really struck me. I’m thinking about it now because I’m not sure that I can write about this book yet. I listened to it on audio—Miller is an incredible reader—but as soon as I finished it I knew I would need to read it again, in print. I knew I had just barley started.

So I will say that this is a remarkable essay collection about many, many things: Jamaica, Caribbean writers, colonialism and tourism, queerness, Blackness, race and its many, many constructs, travel, poetry, many kinds of lineages, family. Mostly it is about silence—the things not said and why they’re not said, and why they matter—and bodies. Mostly it is about bodies. Mostly it is about how the world is made of bodies. Miller writes about what lives in the body, which is everything. He writes about how race is of the body, inextricable from the body, how the way race is constructed in our world is bodily. He examines the way the world moves through him, and the way he moves through the world, in a Black, queer, male body. The essays are deeply personal and intimate and wonderfully far-ranging. But always, always, Miller returns to the body. He refuses to leave it alone.

In an essay about race and colorism in Jamaica, the body is central. In an essay about several Caribbean white women writers, which is also an essay about home and place and what it means to belong, art-making and capitalism, reckoning and denial, the body is central. In three incandescently beautiful and heartbreaking epistolary essays, to James Baldwin and Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, he returns to the body. In an essay about family secrets, about the stories left untold and the stories those untold stories become, he writes into and of the body. He writes, in one essay that I will be thinking about for the rest of my life, about the crimes that haunt bodies—about the crimes that haunt his body, and those that haunt his sister’s body, and how those hauntings are not the same, and how these different hauntings define how it feels to inhabit a body.

This all feels so small and banal to write. I cannot do it justice. Miller’s writing is gloriously alive, rigorous and thoughtful, analytical, curious, poetic. His ideas are big and unwieldily. The questions he asks do not have answers. The questions he asks are about the body and its languages, about silence and its uses, and about where these things intersect, which, it turns out, is everywhere.

The Bake

Remember a few weeks ago when I said I was going to make a bunch of recipes from one cookbook and then write up a little review of the whole book? Well, that didn’t happen. I had to return Mayumu: Filipino American Desserts Remixed to the library before I could make more than one recipe from it (adobo chocolate chip cookies). I did love flipping through it, and I flagged so many recipes! It’s definitely a book I’ll either check out again or buy.

In the meantime, I made a cake to summon fall last weekend. I am so deeply over summer. It seems like my summoning worked, at least a little bit, because it is no longer 90 degrees and sunny. It was 58 at the lake this morning, and it’s raining! I’ll take it.

Apple Spice Cake

Can you guess where this recipe comes from? Of course you can! Snacking Cakes! It’s a lovely spice cake full of brown sugar and cloves that tastes like October. It was a little denser than I was expecting—maybe because I poured the glaze on when it was still too warm, or maybe because I didn’t quite bake it long enough. It was still delicious.

If you’re looking for a fantastic breakfast cake, this is a good one. It’s not my favorite cake from Snacking Cakes, but it’s a good one. Arefi hasn’t let me down yet.

The Bowl & The Beat

The Bowl: THE Breakfast

A few years ago, I started making a salad with greens, grated beets and carrots, pecans, raisins, and blue cheese. It was so good that my bestie and I started calling it THE salad. I guess this is our thing now, because earlier this summer when we spent a few days together, we started making kale with Parmesan and summer squash for breakfast, and now it has become THE breakfast. I promise it makes a really good dinner, too.

The key bit here is the cheesy kale. Slice a summer squash into half moons. Heat some butter in a skillet and add the squash. Fry over medium heat until it’s starting to brown. Add a bgi handful of chopped kale, along with some salt and pepper. Cook for a few minutes until the kale has wilted. Then grate a ton of Parmesan right into the pan. Don’t be shy! Stir it all around so that all that melty cheese nicely coats the kale and squash. Serve with assorted accompaniments. My favorite is a bagel with cream cheese and pickled onions, a fried egg, and sliced tomatoes.

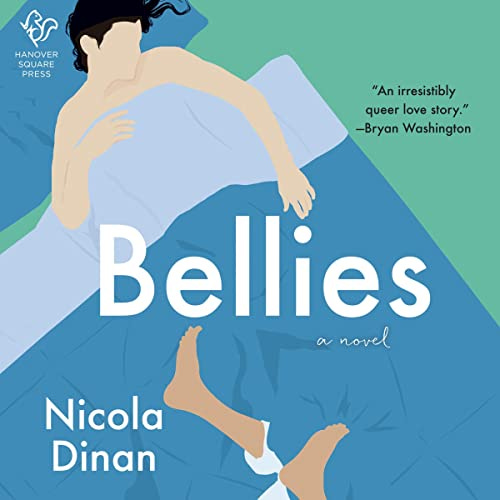

The Beat: Bellies by Nicola Dinan, read by Nathaniel Curtis and Octavia Nyombi

Yes, I’ve already read this, and yes, I raved about it! I love rereading books on audio that I’ve recently read in print. There’s this sweet spot, when it comes to rereading, about 3-4 months after the first read, that I rarely catch, but when I do, it’s a miracle. There is something delicious about rereading a book soon enough after reading it for the first time that it’s still fresh in your mind, but far enough that the details have started to get hazy. This novel is just as good the second time, and both narrators are fantastic. If you haven’t read it, I don’t know what you’re waiting for.

The Bookshelf

Around the Internet

On Book Riot, I made a list of some nonfiction coming out this fall that I can’t wait to read, as well as some of my most anticipated fall poetry collections. I reviewed Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote for BookPage.

Queer Your Year

Thanks to everyone who participated in the August raffle, and congrats to Cheryl, who won! This month’s prize is a fun one—I’ve put together a Mystery Queer Book Bundle! You’ll get five queer books: a mix of ARCs, paperbacks, and hardcovers in a variety of genres: nonfiction, poetry, fiction, science fiction, and a speculative novel. Check out all the details here!

As always, don’t forget about the super fun prize packs! Everyone who submits a game card gets one, and they ship internationally. And please come join the Queer Your Year discord if you haven’t already! If you’re stuck on a prompt (or just want to chat about queer books), it’s the place to be

The Boost

Dani Roulette (@thunderbirdwomanreads) is one of the best people on Bookstagram, and she’s shared her love and knowledge of Indigenous lit with me and so many others. She’s currently raising money to support her during her upcoming cancer treatment. Please donate if you can.

As always, a little bit of beauty to send you on your way: I am done with summer, but I am not done with the lake.

Catch you next week, bookish friends! I have no idea what next week’s essay will be about, but if you want to read it, you can subscribe here.

So sorry you didn't get the job you wanted — I know it happens to all of us, and yet it's still disheartening. Sending love your way!

I also LOVE that you've been getting in the water. I am landlocked and without access to a pool (literally one of the reasons I'm moving) and I cannot wait to make swimming a more regular part of my life. Like you, I believe there's something magical about it, and it can't fix everything, but it sure does help.

I’ve been trying to swim in a body of water this year too, and it’s been so fulfilling I wish I started doing it earlier. ❣️