Greetings, book and treat people! Last week I wrote about swimming at Ashfield Lake in the mornings. Since then, I have been there every morning save one (and that was because I went on a different morning adventure). I’ve come to love the drive (i.e. my new daily commute). I cannot image my mornings without the lake anymore. I wasn’t planning to go on Sunday—but I woke up and my body said, “take me to the water,” and I said, “okay, of course, whatever you need,” and it was perfect.

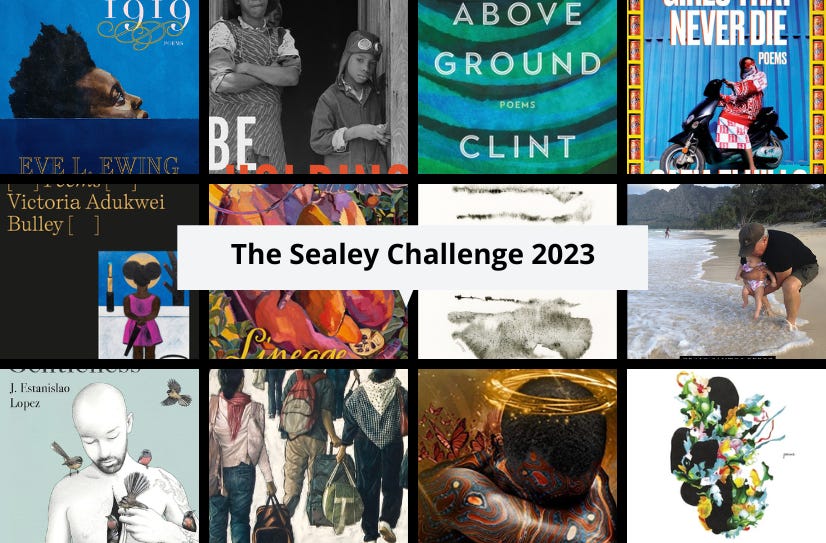

It’s the fifth week of the month, which means today’s newsletter is a special edition for all subscribers. This is my third year doing The Sealey Challenge, which is my favorite thing about August. I’ve been writing about the collections I’ve read in groups of three on Instagram, focusing on a common theme between the books. It’s been such a wonderful way to reflect on my reading, as all the themes have arisen naturally. I’ve learned a lot about poetry, and, as always, I’ve discovered some incredible new-to-me poets.

It’s also time for the August Queer Your Year Raffle! This month’s prize is a fantastic bundle from Mama Hen, including a scrap infinity scarf (so pretty!), a pack of cloth wipes, and a pack of cloth rounds. You can submit your game card and find all the details here. You have until September 3 to submit. The winning prompts this month are: 4, 9, 16, 29, 38, 41, 42 and 48.

And now: poetry!

Days 1-3: Variations on Complicated Girlhoods

I Shimmer Sometimes, Too by Porsha Olayiwola

This collection is about Black queer girlhood. Girlhood shadowed by state violence. Girlhood built beautiful out of music and sisters and city streets. All the possible girlhoods lost to racist violence, and the ways the speaker’s Black womanhood—fat, loud with pleasure, riotously queer—honors and reinvents and holds those lost girlhoods.

"& i think about my name how it is the first gift i gift to a stranger the first thing that was mine i ever gave willingly to the world"

I love this poem.

Poukahangatus by Tayi Tibble

Poukahangatus is about Māori girlhood, pop culture girlhood, girlhood in the age of Twilight and Instagram. Girlhood haunted by the girlhoods of mother, grandmother, ancestor, myth. Girlhood tangled with desire. Girlhood tied to family story, becoming story.

"Remembers how it feels to have her body strummed by wind coming in from the ocean. The way the taste of wild mint is like an echo in her mouth. How hunger feels like hellfires and hope feels like walking up a dead riverbed searching for a trickle."

Here is a great poem from the collection.

Tunsiya-Amrikiya by Leila Chatti

This collection is about girlhood between—languages, homes, memories. Muslim girlhood, girlhood of wildness, girlhood held gently in family, in food, in ritual. Girlhood torn by American violences, rewoven into untranslatable, powerful womanhood.

"If there exists in my blood a map, it is one I keep folded for fear of where it does not lead."

Days 4-6: Holy, Haunted, Ordinary Vessels

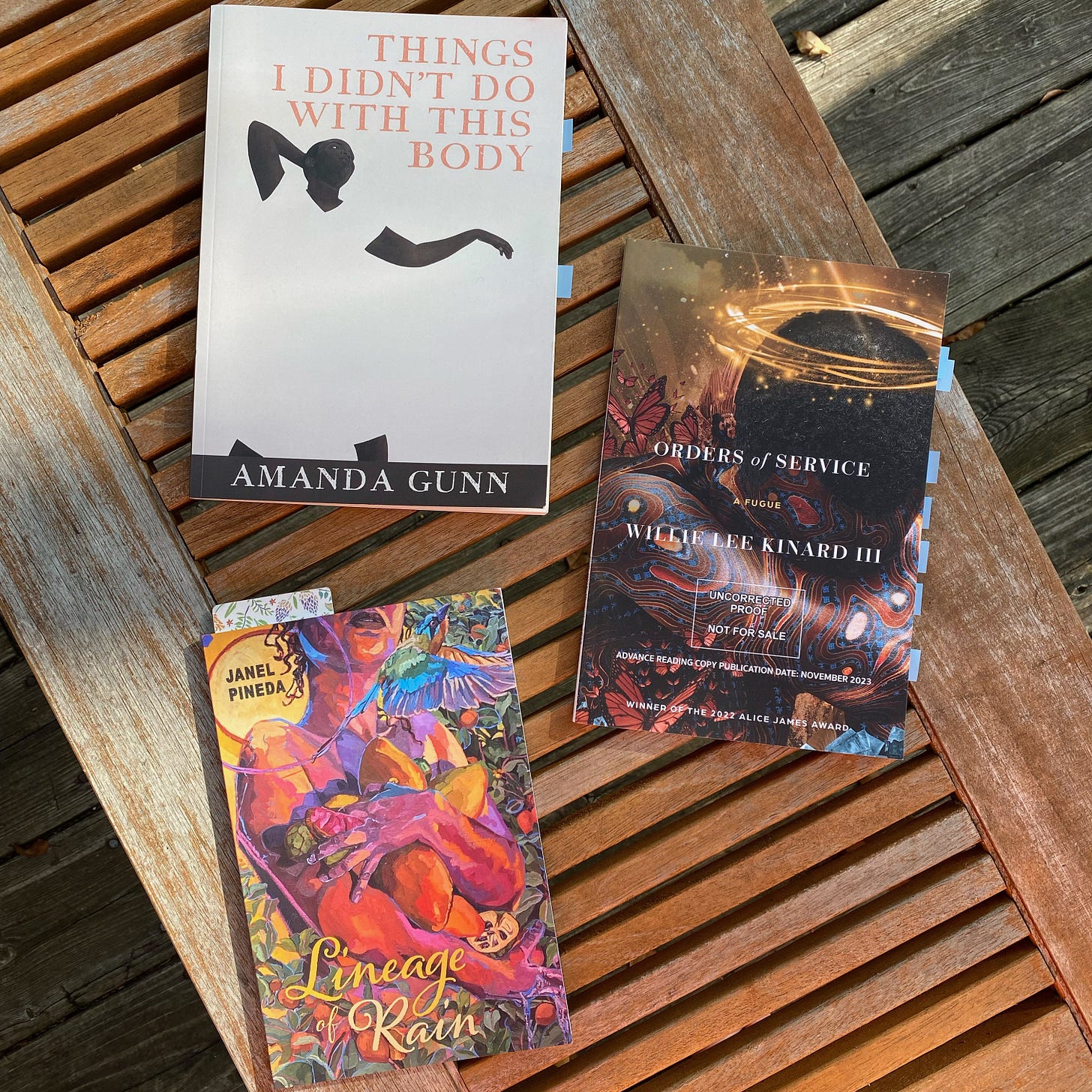

Orders of Service by Willie Lee Kinard III (November 14, Alice James Books)

This collection is about holy vessels, remade. It’s about the Southern Black church, about song and hymn and choir. Song as vessel for escape, hymn as vessel for praise, choir as vessel for what cannot be named. Some of the poems that struck me the most are about bees and crickets—insects, nature, wildness as a way to queer the world and the word. The speaker tangles with their Southern religious roots, restrings them, makes of every contradiction music that’s a vessel for change and homecoming, sorrow and elation.

"We collapse into each other. The moon of him eclipsing the fullness of me, the rift of us unfolding unto new darkness & what are we but ravenous? Here, we devour dusk, suckle sides of cosmic gristle, mouths brimming, tearing the sky, Black."

Things I Didn’t Do With This Body by Amanda Gunns

Body as vessel, body breaking. Body split open, body touched, body splintered, body sick, body longing, body still—everything the body holds, poemed. Bodies as vessels for pleasure, violence, words. It’s about pills as vessel—for oblivion, for complicated healing. And about the vessels of healing—how is it delivered, and in what container? There are so many food poems, rooted in the material realities of kitchens—pans, mixing bowls, eggs. Food as vessel for love, softness, family. The poems themselves are vessels for rhyme that snaps and surprises, forms that hold more than feels possible.

“I’m 42 will I get better what’s better what’s human is it OK to have feelings is it human to be a rock what about a flood is it OK to cry if it’s only a little”

Lineage of Rain by Janel Pineda

While I didn’t love Lineage of Rain as much as the other two, I still enjoyed it, especially the poems about language. What kind of vessel is a language, Pineda asks. What does language hold? What can’t it hold? What does it break? My favorites are the poems about her Salvadoran grandmother’s, and her own, relationships to English and Spanish. There are also some beautiful, heartbreaking poems about migration and belonging and fleeing from violence and what women carry with them—and what kind of vessel their descendants become, for loss, remembered trauma, strength.

"They ask your name. To ask your name is to ask your life. You do not have another's to borrow."

Days 7-9: Guided, Guiding, Guides

We Borrowed Gentleness by J. Estanislao Lopez

We Borrowed Gentleness is full of curiosity and anguish, guides complicated and forceful, tricksters and lovers. The poems about God, and the retellings of Christian mythology, are stunning—specific, rending, full of the loneliness of finding a way through the muck. Who guides us and how do we guide? What happens when the guides we’ve looked to all our lives guide us into mess and violence? How do we guide our children, and how do they guide us? What guides us through a burning, flooded world?

“All you can offer anyone suffering in the world is a sentence, which is more often than not not enough.”

Here’s a taste of the music of this collection.

Domestic Work by Natasha Trethewey

This is a collection of photographic portal poems, a specific and beautifully detailed meander through Black American history and back into the present. Many of the poem titles are place names and dates (“Drapery Factory, Gulfport, Mississippi, 1956”) and others are simple action words (“Housekeeping”, “Gathering”). They capture explosive and quiet moments. Their attention to dailiness took my breath away. I thought about what it means to look backward for guidance, about what kind of guiding ancestors do, unknowing, and what guides live in the real and imagined lives of those who before.

"Under-ripe figs, green, hard as jewels—these we save, hold in deep white bowls. She puts them to light on the windowsill, tells me to wait, learn patience. I touch them each day, watch them turn gold, grow sweet, and give sweetness back. I begin to see our lives are like this—we take what we need of light. We glisten, preserve handpicked days in memory, our minds’ dark pantry."

Against Heaven by Kemi Alabi

This collection is hard for me to write about—it’s a riotous, elegiac, keening, Black queer celebration. I loved it so much and need to read it again to untangle it. Alabi’s words are ropy and new. They tie language into impossible knots and they tug them loose. I’m thinking of language and how it can guide us into the unknown, about how words as guides can open worlds. Words like “heatmapped”, “dizzytrip”, and “unstranger”. I’m thinking about the backwards and the beyonds of this collection.

“Be cloudthick and unpartable. Be tangled, skystruck waves.”

I love this poem.

Days 10-12: The Stories Only Poetry Can Tell

I’ve been thinking about the stories only poetry can tell, and what that has to do with breaking. Poetry is a form that’s good at breaking. As I read through these collections, I couldn’t stop thinking about how they are all wrestling with what is broken—systems, parts of the body, relationships, even the self. Poetry does not strive toward wholeness the way novels so often do. It allows for breakage after breakage. It is literally made of breakages—words severed from each via line breaks. There’s something here, something I haven’t gotten to the bedrock of, about the way the world breaks, the way we break inside it, and how when poetry breaks it becomes an invitation, a way to tell stories that cannot, will never, be whole.

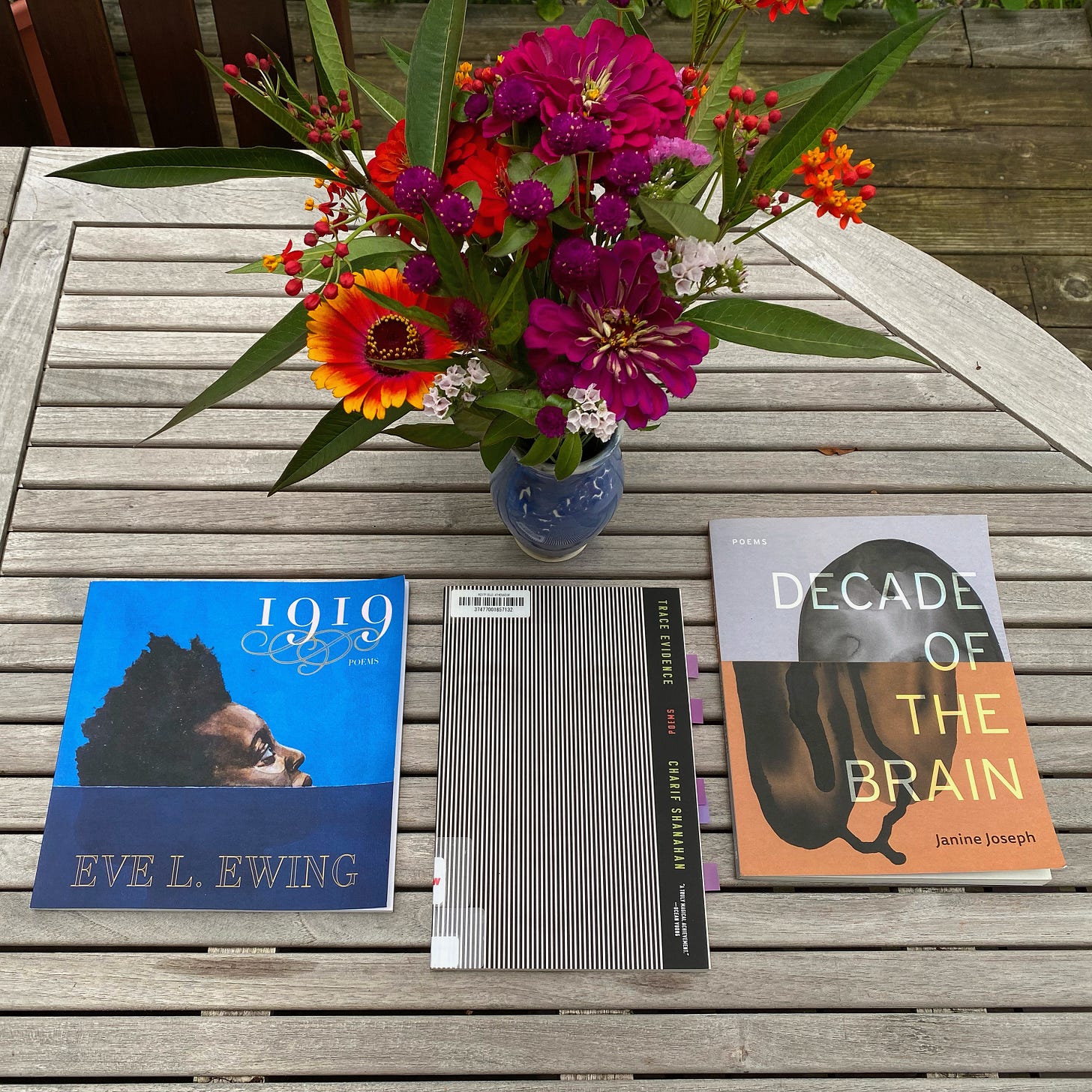

1919 by Eve L. Ewing

1919 is about the 1919 Chicago Race Riot. The poems take many forms—Bible verses, fables, lists. Ewing writes about the riot itself, as well as the before and after—the Great Migration, segregation, police violence, the everyday-ness of Black life in Chicago. The poems are all in conversation with a 1922 report, “The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot” and excerpts appear throughout.

I do not have the words for the brilliance of this book. Ewing transforms and remakes an archive. She tells the story and the story behind the story and the story behind that one. Poetry opens in a way that prose can’t, and Ewing uses it to do something extraordinary. This book hurts and hurts and hurts. It is expansive and intimate, rooted and full of sky.

"you, thief of dusk, you, captain of my sorrows. you, avarice. your ground is greedy for our children, and you take them as you please."

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph

Decade of the Brain is about experiencing and healing from a traumatic brain injury. I often found it hard to understand these poems—they happen out of order, all over the page, in strange and overlapping shapes. But how do you write about such tangled memories? How do you write a circular process, a healing that moves in weird time jumps, memory jumps, forward and around and back? How do you put such a surreal experience into words? I’ve been sitting with it and I love everything this collection leaves out—the spaces, the questions, the easy-to-follow paths. This is something else poetry does—you can get lost inside it and still feel moved by it, struggle through it still awash in the wonder of words and their music.

"Always now I sense in the wrong tense; without memories, there is only likeness."

Trace Evidence by Charif Shanahan

This collection is about so much, but the long central poem is also about an injury—a severe neck injury Shanahan sustained in a bus accident in Morocco. This meandering poem is full of questions, meditations on race, home, homeland, lineage, memory. All of this is wrapped up in the speaker’s relationship to his mother and her home country of Morocco.

Much of the rest of the book is about the construction of self and identity—how do you construct a self in a world in which everything is constructed? It’s so cerebral, so preoccupied, full of repeating words and images. Yet it is also so deeply of the body: how it feels to live inside skin, to long to shed that skin, to move through days. Shanahan is so sharp, so tender, so curious. Poems about sex, queer desire, familial breakages, longing for “the answer”, internal and external knowledge, the messy contradictions of racialized identity—are all speaking to each other.

"I have the space inside my body to feel The two men, their commitment To pleasure, absent basic comfort: The one’s face nearly neutral, as though His friend’s mouth and the sting of existence Canceled each other out."

Here’s one poem I love. Here’s a review of the book I love.

Days 13-15: Who Are You Writing To?

I loved all of these collections, but struggled to connect them thematically. They are all deeply specific and have incredibly cohesive poetics. Each collection feels like a small world. This, then, is how I’ll connect them: in their specificity of address. What strikes me about all these collections isn’t so much that they are written for specific audiences (though they all tangle with specific identities and communities), but that the poems themselves feel like a form of address, a reaching outward and toward.

Maybe the question here isn’t who these poems are written to, or even who is writing them (a fascinating question, there are so many layers of identity!), but what they don’t give away. What spaces open in poetry, in the world, when you refuse to to give away pieces of yourself in order to be universally legible?

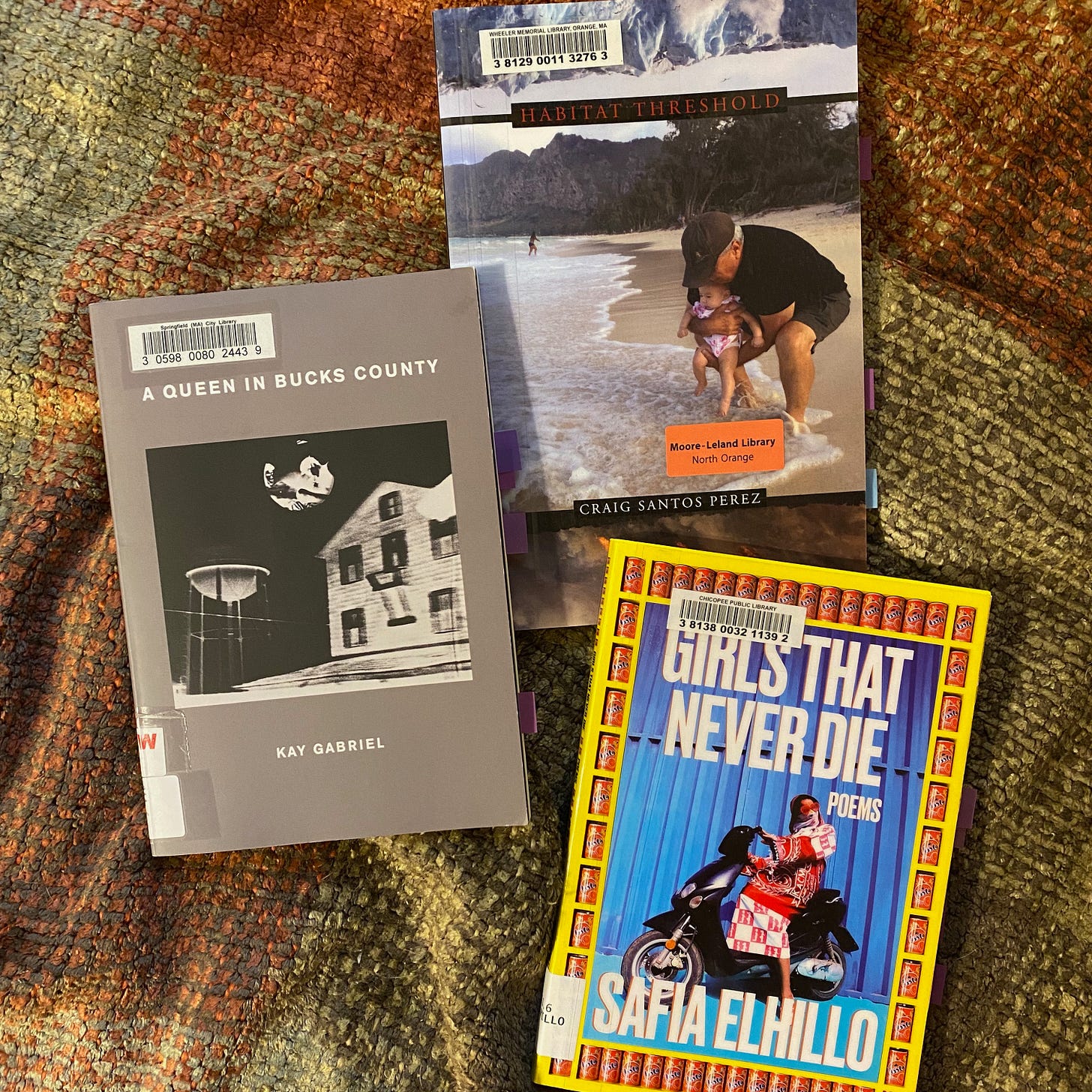

Habitat Threshold by Craig Santos Perez

This collection reaches toward the earth. Perez’s poetry is accessible, sometimes straightforward, but not empty or easy. It’s about fatherhood, climate grief, Indigeneity, American violence, Hawaii, oceans. But always, Perez speaks to the earth and the places where we touch it.

"May we always remember: love is our wildest oceanic instinct."

Girls That Never Die by Safia Elhillo

This is an address to girlhood. It’s searing and heartbreaking and full of rage, and tender. Look, Elhillo says, look what happened to us, so many of us, what is still happening to us. It has an eruptive energy. It never stops moving. Even the poems that are not directly about girlhood are infused with it.

"& isn’t a map only a joke we all agreed into a fact & where can i touch the equator & how will i know i am touching it & where is the end of my country the beginning of the next. how will i know i’ve crossed over"

Here’s a bit more of her work.

A Queen In Bucks County by Kay Gabriel

What a horny, playful, deliciously ordinary book about queer and trans life. It’s a collection of poems as letters, addressed to friends and lovers, all written by Turner, a character who makes a beautiful mess of every border, every binary. I am still wondering who these letters are written to. I can’t wait to read this book again. I was lost through much of it, and yet the overwhelming feeling it left me with was wonder. Gabriel, I think, is writing both to and inside of queer and trans bodies, memories, desires.

"Good hell morning I haven’t slept again I think I’m amorous infrastructure"

Days 16-18: I Have Preferences

I couldn’t come up with a theme connecting these collections. Sometimes books don’t speak to each other. Instead, here some thoughts on these collections in the order of how much I like them.

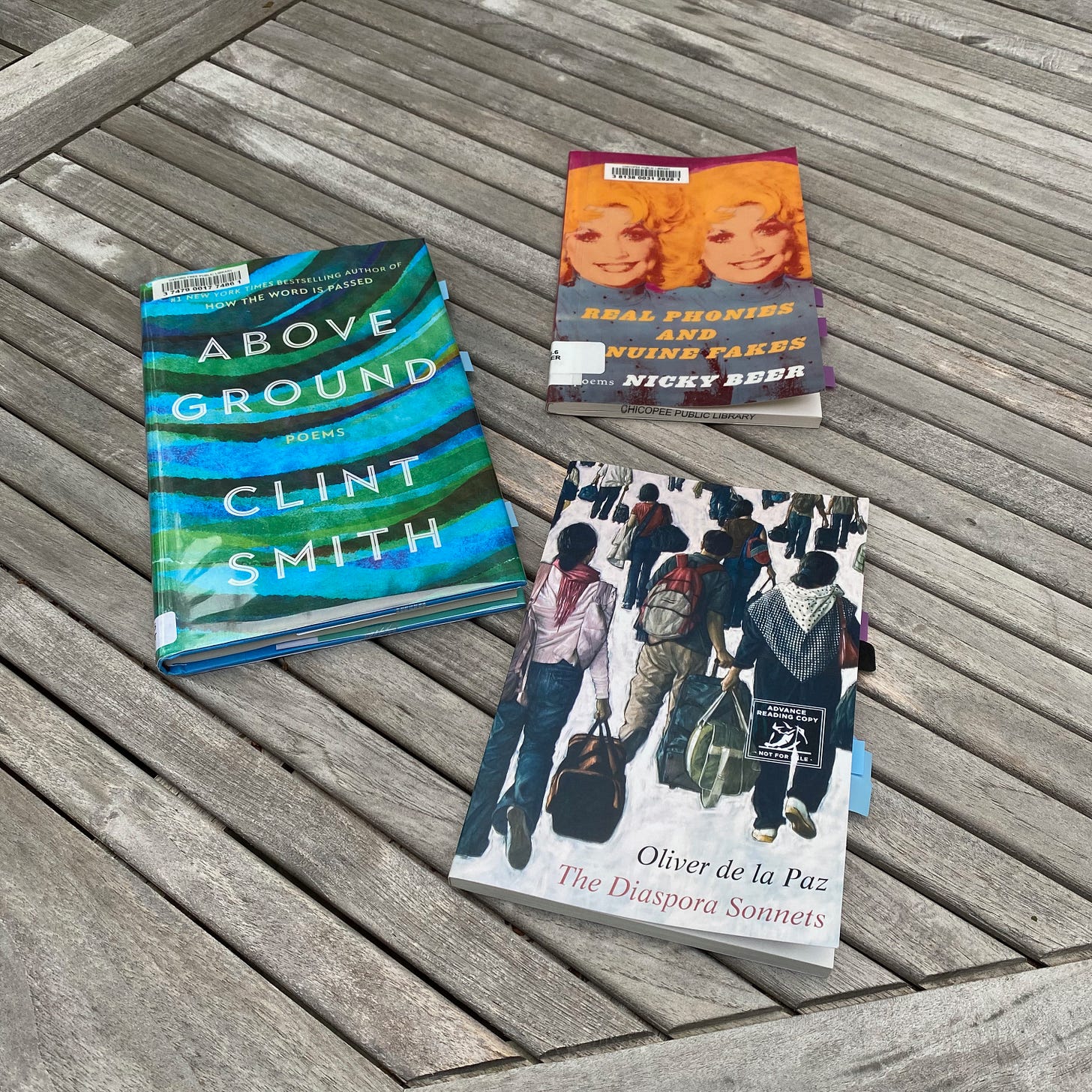

The Diaspora Sonnets by Oliver de la Paz

This absolutely took my breath away. It’s split into three sections, each beginning with a chain migration poem (an invented form?) and ending with a pantoum. In between, sonnets. De la Paz’s writing is so precise, so sharp, each word weighted, his line breaks like little cliffs, his imagery surprising and inventive and full of movement. I read these sonnets over and over again and every time they broke me. De la Paz gets the sonnet to open and open and open and burst.

The poems are about his immigrant family, migrant work, tangled parental relationships, fruit, the American West, deserts, roads, plants, ghosts, grandparents, what it means to leave a place, home, the Filipino diaspora, and and and. I could feel my heart beating as I read them, the longing, rolling life in them, the earth of them. Many of them made me cry. I can’t wait to check out the rest of de la Paz’s work, and to read this book again.

"My prairie exile does not show itself on any map. I am vapor and ash in conversation with the citizens in trees above, more resident than I."

I will never get over this line breaks and meter.

Above Ground by Clint Smith

A tender collection about being a father. Many of the poems are addressed in the second person to Smith’s children. They are full of love—for the world and for family—and also fear, despair, uncertainty. Some are very funny. Smith writes beautifully about the banal, his voice is intimate and immediate. There is a lot in here about being a Black father to Black children, as well as dinosaurs, sea creatures, gardens, sleep schedules, exhaustion.

"Tiny plankton in bodies of water like this one produce over half of the oxygen on earth. My life is made possible by trillions of tiny mysteries."

Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes by Nicky Beer

This is an interesting collection about pop culture, movies, bodies, taxidermy, magicians, the weird in-between places where people find themselves. I liked the mix of lighthearted and serious poems, but they didn’t lodge themselves inside me.

"Say that it’s the reassurance of the omnivore: we can’t choose the feast that will sustain us—our only power is to greet the terrible and joyous alike with our souls’ most ravenous yes."

Days 19-21: Circles, Spirals, Loops

These collections are about the impossibility of return. They’re about how time and memory and grammar trick and flip, how experience circles itself. These poets write into the cracks, the lost places, the spaces between then and now, here and there. They make endlessness out of what’s perceived as linear: migration, loss, words on a page.

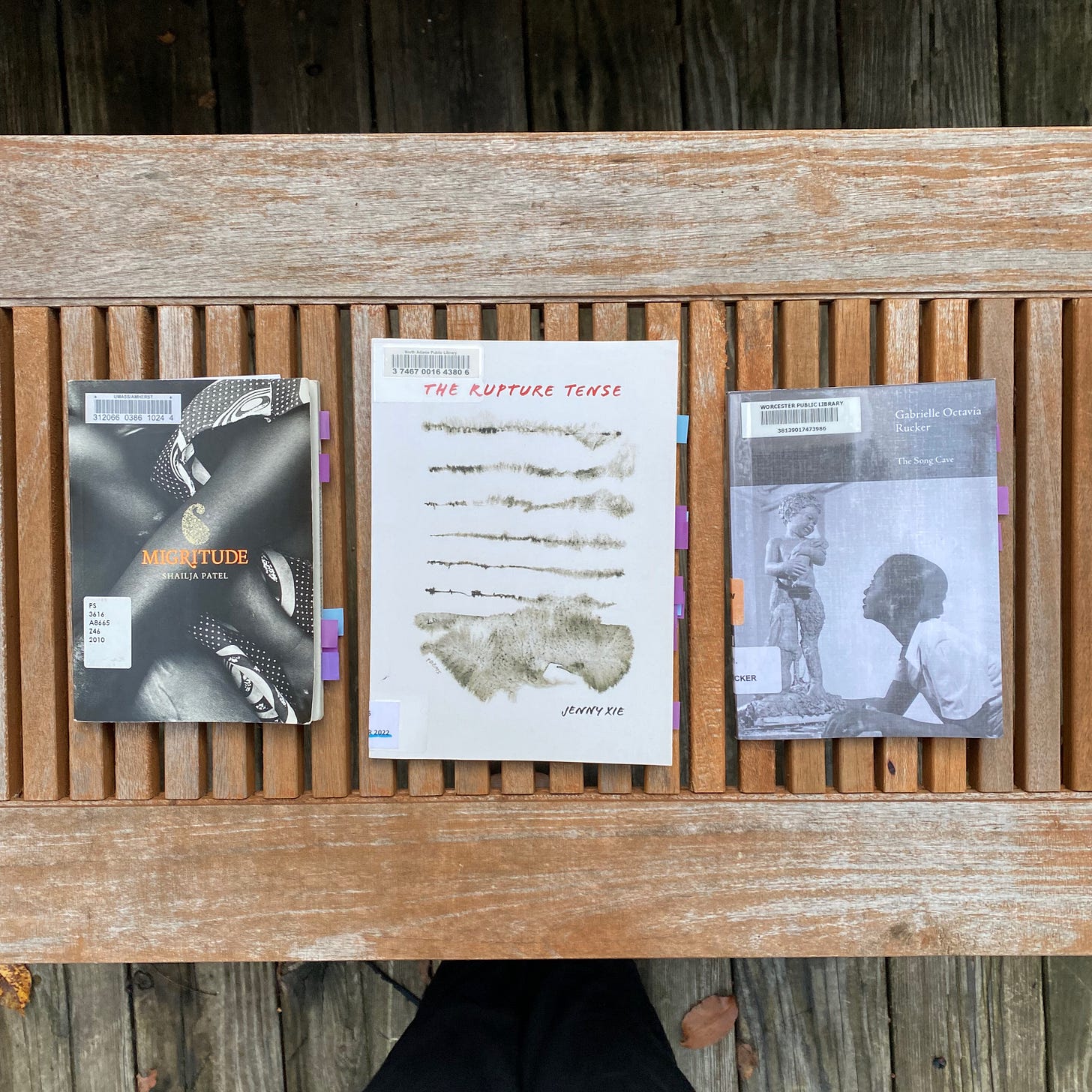

Migritude by Shailja Patel

This genre-bending book is a translation/expansion of Patel’s one-woman show of the same name. She traces her own history as a brown Kenyan of Indian descent, as well as the broader history of Indians in East Africa. The work traveses contents and languages and homes in a thousands ways, marking complex lines through memory, ocean, myth, political upheaval, genocide, letters, treasure. For Patel, migration is not a destination, a journey to/from, an act. It is a continuing movement, a built environment, a muscle, a way of experiencing the world, a language.

The centerpiece of the book/show is a chest of saris given to her by her mother, which become openings and spirals of story. This book is gorgeous and tangled and deep. I could read it again and again and never be done with it.

"But Mummy, look. I am forging a ship of glittering songs to sail your jewels in, staking a masthead of verbs from which to fly your saris!"

The Rupture Tense by Jenny Xie

This collection is precise and rending, an aching, gaping hole of a book. It’s about what breaks and how to speak the breakage, about what grows in the break, about what cannot be repaired. Most of the poems are about Xie’s family during the Cultural Revolution. There’s an impossibly beautiful and heartbreaking sequence in conversation with the work of Chinese photographer Li Zhensheng. In another poem, Xie recounts a conversation with her grandmother, missing words depicted as bracketed empty space.

The way Xie writes about grammar and language is extraordinary. She’s constantly pondering tenses. What tense does memory happen in? How does distance change the tense of an experience? What tenses do ghosts inhabit, and in what tense do we dream the figure? This book will live in my body for a long time.

"The left-behind and the dead are alike: they travel shouldering a simple bag, and form the lightest of predictions about how to make a passage."

Here’s a taste of her brilliance.

Dereliction by Gabrielle Octavia Rucker

I’m fascinated by the white space in this book. The first section, ‘Murmurs’, is a 40-page poem with just a few lines on each page. I couldn’t tell you what it’s about, but I felt it, the words, the lines, the yearning to translate feeling into ink. This book is a spiral in that it seems to be an endless question: who is speaking? Where are they going? How does this moment connect to this one to this one? Each page of Murmurs feels to me like a small world, exploring bodies, desire, nature, breaking relationships, language, despair. I’m not sure what they add up to. I’m not sure they’re meant to ‘add up’ to anything.

The second section, ‘Dereliction’, is made up of more traditional poems, but it carries the same strange momentum, the same mystery, the same restlessness. This collection resists simple interpretation. It does not want to be pinned.

"Moonlighting as girl-child russet fleshed / pink-feathered first born, uplifted every claim assured— Gift given: three scarlet ibises hatched from the Sun."

This is a really interesting interview with Rucker.

Days 22-24: Language-Feeling is What I’m After

If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?

I often think about this quote from Emily Dickinson. I don’t necessarily agree with it—I mean, there are lots of other ways to know a thing is poetry. But I understand what’s she’s saying, and I like the language she uses to say it. What does it even mean to “feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off”—it’s not a sensation that’s describable. It’s a totally absurd and dramatic way to explain a feeling.

This, too, is how I feel about poetry that I love. It evokes a feeling in me, and the feeling is rooted in language, inseparable from language. It is a feeling built of words. The poems can be about anything—breakfast, violence, queerness, trees, grief, colonization, ecology, singing, sex, heartbreak, dogs. The subject matter is incidental. A poem about anything can evoke the language-feeling, even poems I do not understand.

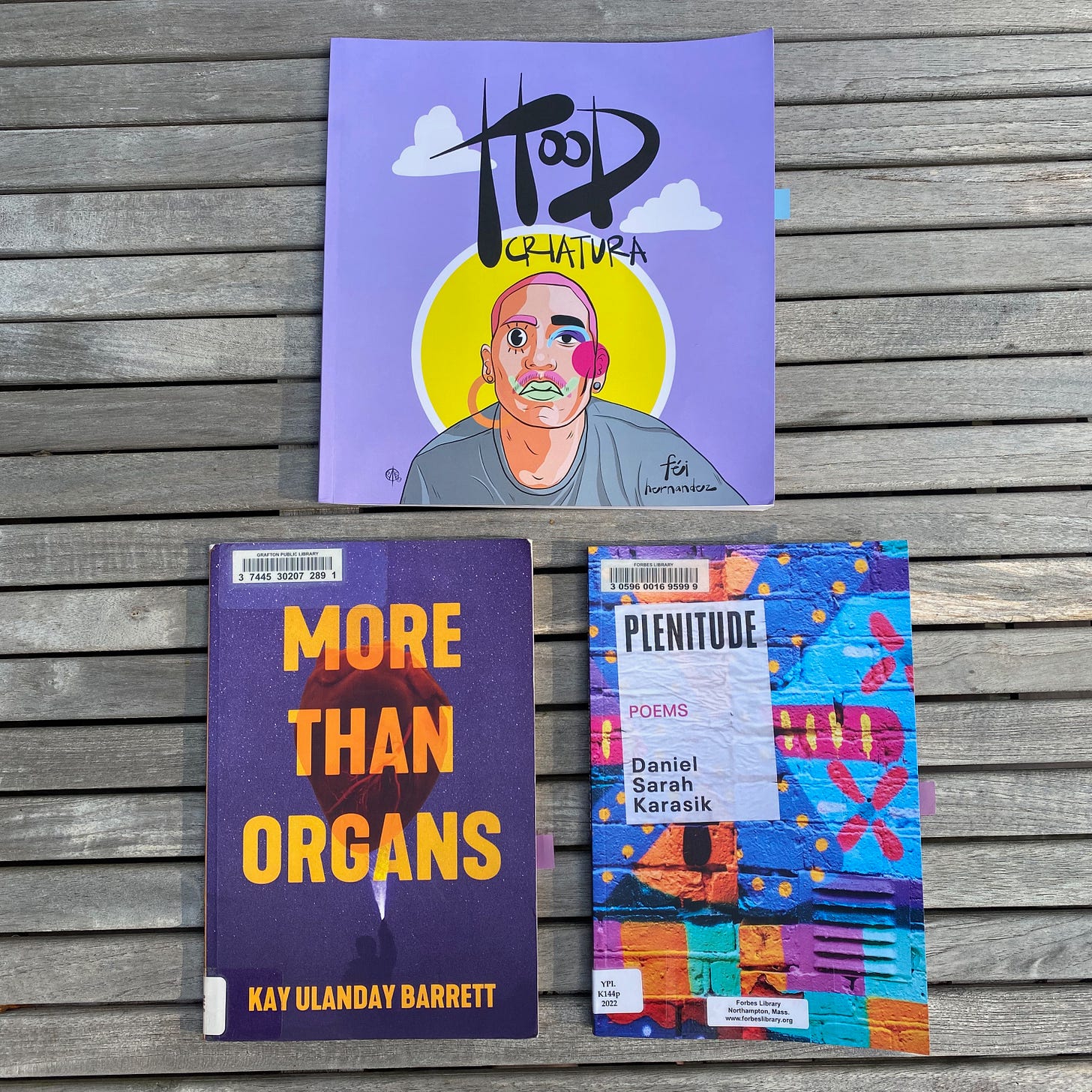

More Than Organs by Kay Ulanday Barrett, Plentitude by Daniel Sarah Karasik, and Hood Criatura by féi hernandez are all about subjects I care deeply about: queer and trans identity, disability, familial grief, the violence of American immigration policies, socialism, activism, gender, cultural knowledge, living in racialized bodies. And yet I felt nothing reading them—and it’s not because I’m incapable of empathy. It’s because the language in them didn’t sing to me. The way these poets threaded words into shapes did not excite, surprise, startle, prick, or swallow me.

I’ve been thinking for days about this stanza from the long, sparse poem ‘Murmurs’ in Dereliction by Gabrielle Octavia Rucker:

“Plot point: a comet is coming to defeather us. Synopsis: stick to the swamp.”

I still have no idea what this poem is about. But this line! The music of each word. The swaying internal rhythms. The click of the directive. The way it delights and breaks me. It means a thousand windows to me, and also: I don’t care what it means because it makes me feel wildly fiery. It fills my body with language-feeling.

I come to poetry for a paradoxical experience: for a feeling that comes from language and is impossible to describe with language. I might say, to Dickinson, that when I read a book and it makes my whole body feel like water, I know that it is poetry. I might say, if I feel like the inside of a wave or the texture of sunlight on my closed eyes, I know that it is poetry. If a book makes me feel like a thunderstorm, I might tell her, then it is poetry.

I don’t think any of these books are objectively bad. For me, by my own definition, they do not do what I need poetry to do. I will forget about them soon. But they might make someone else’s body into a songbird or a bud—it’s impossible to predict.

Days 25-27: Refusal

I loved all of these collections. Each of these poets refuses—by which I mean opens, by which I mean honors, by which I mean builds anew—in different beautiful ways

Look by Solmaz Sharif

In this collection, Solmaz refuses, I think, to give away language. Strewn throughout the collection are words in capital letters taken from a Department of Defense military dictionary. They are shocking to come across, and yet, the more I think about it, the more interested I become in what Sharif is refusing by taking these terms of violence, empire, destruction—and putting them in poems. She shifts their meaning by putting them into poems of grief, homeland, distance, longing, resistance, witness. What do they become? What meanings are layered beneath them? Are they transformed? Stolen? Wrestled back? Who does language belong to?

There is also a lot of refusal in this collection in the form of silence—white space, redacted words—that is both sacred (secrets not revealed, home not splintered), and coerced (state censorship, histories rewritten).

"And I place between us a bar of laughter And I place between us the looking and the telling they want dead"

I can’t wait to read some of her other work.

Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley

In this extraordinary book, Bulley writes into quiet as a kind of refusal—a refusal of the white gaze, of silence, of invisibility, of visibility. These poems are dense with interiority and movement. I felt acutely aware of my body while reading them. Partly this is because the rhythm and spin and density of her lines and images—they kept catching my breath. But it’s also because of how deeply and simply these poems go into the secret spaces of feeling and knowing yourself. I also felt acutely the gift of me/not me, i.e this is a book in and of and from Black womanhood, not for or to me, and this is a book about being embodied in a breaking world, for me and to me.

"Here we are, gone, finished, so scrutable beyond saving. Here are we, way out beyond the wash & nobody coming. Here is where we admit what we won’t say with our mouths Say, instead, tongue to opening, thing to ear, fold to fold, how we know We aren’t going to fix the world & no one is coming. & here, How we cope: one hundred million of you flung out onto the lawn. A pointillistic offering—no two the same. In our leave-taking, we do What we can. The hedges are high enough. Your neighbors, long dead. We step out of our bodies & into the light."

This is one of my favorite poems in the whole book.

Be Holding by Ross Gay

This is a work so buoyant and new I know I’ll never be done with it. It’s a book-length poem about basketball, but really it’s about flight and Blackness and photography and how we look and don’t look and see and don’t see and the practice of holding and beholding.

It’s been a long time since I cried so hard reading a poem. The craft is world-shifting, in the way the craft of Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is world-shifting. I could make a list a mile long of the things Gay refuses in this work, but the main one, I think, or one of the main ones, is that he refuses to land. He sets something in motion that is continuous. Or rather, he picks up the notes of a continuous song, as he so beautifully writes in the acknowledgments:

I want to honor the mycelial way poems are made, but not only poems. Lives. Our lives, each other’s lives, I’m saying. The black walnut tree dappling the morning sun coming through the window. The blue jay alighted in the shadows long enough to sing something that entered this singing. All that which has moved into me so deeply that I don’t even know it wasn’t always there. All the singing that makes this singing. All the singing without which this little song would not be. All the singing. All the beloving. All the generations. Who loved you before they knew you. More than we will ever know. Gratitude.

I can’t wait to watch him read the whole poem.

Days 28-30: Too Much

I have loved almost every moment of this challenge, but I am glad it’s just about over—I’m starting to feel overstuffed, too full of words, a little bit drunk on poetry. I suspect there are connections to make between these three collections, but my brain keeps bouncing off of them. So here are three mini reviews instead.

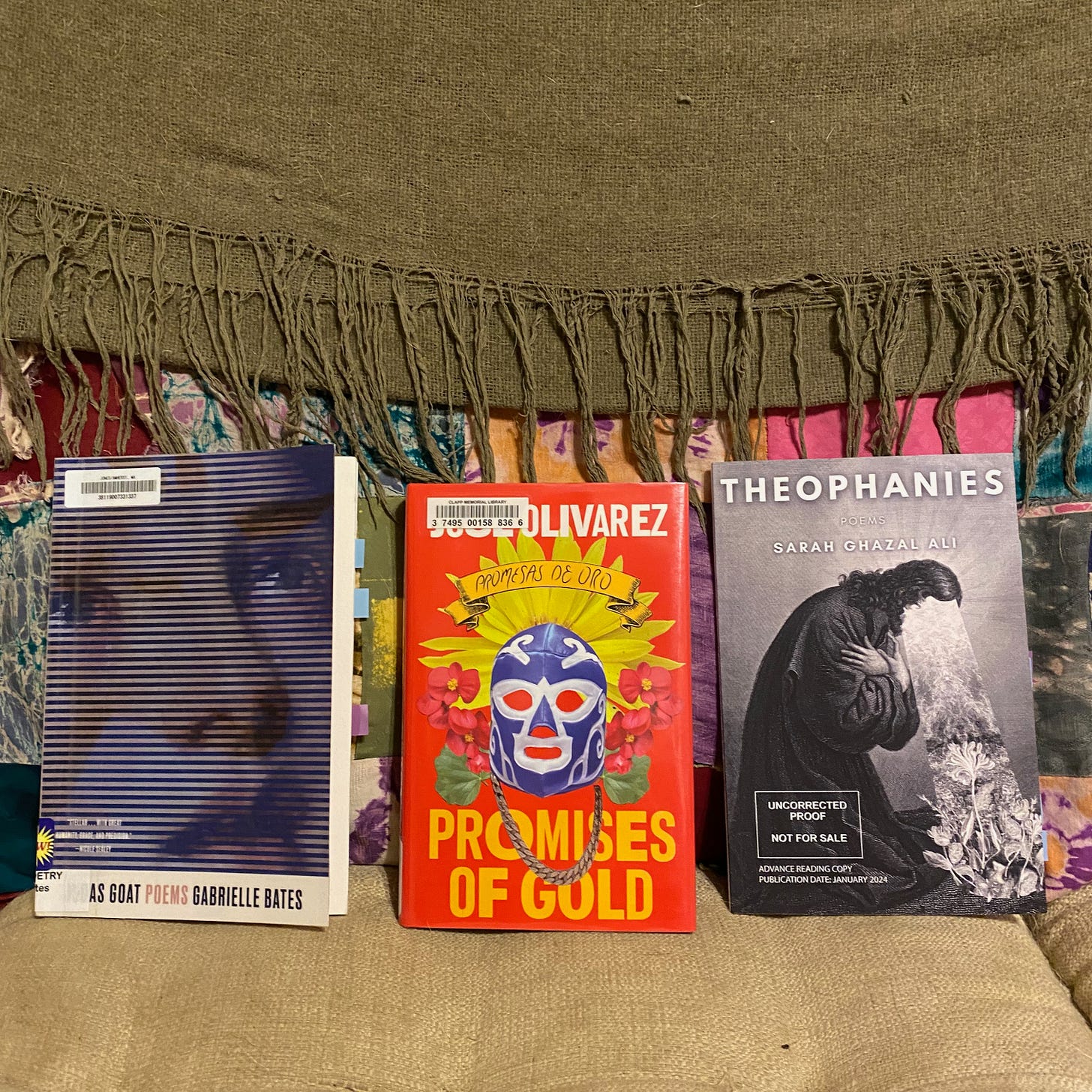

Promises of Gold by José Olivarez

This is a very direct, unfussy book about love: friends, lovers, siblings, places. It’s not my favorite kind of poetry—it rarely gave me that language-feeling of shivery surprise. I did eventually just settle into it, and I enjoyed reading it for what it was: short poems about the things Olivarez cares about, simply stated. There’s not a lot beneath these words and lines that I could find, and that’s okay. I know it’s the sort of poetry that makes some people’s hearts beat faster!

one of the first questions our ancestors had to answer was what to do with the ones who die. at some point, that started feeding the dead back to the ground & naming babies after them.

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali (January 16, Alice James Books)

Oh, this collection opened and gutted me. It’s about Muslim womanhood and complicated mothering (mothering of words, mothering of bodies, mothering of history, mothering done in secret, mothering longed for, mothering in faith, mothering the self, mothering of mourning). It’s about violence done to women and it’s about holiness and sacredness and where to find it—in bodies, in ancient texts, in ritual, in secrets, in the carving of space. There is so much about language and place, what happens when you lose them or they lose you. The ghazals are especially stunning. But every poem—practically every line—felt to me like a precise and gentle cut. Oh, this is how the world is. Oh, this is how it hurts. Oh, this is how it sings. The imagery is electric, wild, it kept awakening in me little startles. It kept waking me up.

Blasphemous how one begets many. Father, father, daughter. & your mother? Miraculous origin—the one safe country. When they ask, Ghazal, if you anger, recite again: men flee the wind for the anthem of a new country.

Judas Goat by Gabrielle Bates

This book has a distinct rhythm, a sharp and pointed meter that I like. The sentences in the poems all feel like cliffs with abrupt drop-offs. Everything about this book feels hard and exact; there’s not much looseness to it. It’s about the ghosts of the place you come from, partnership, violence, escape. There are a lot of visceral and striking poems about bodies, mostly women’s bodies, and a lot of poems about animals, sacrifice, religion, what it means to conform or believe. It’s very confessional—the speaker always seems to be striving toward revealing secrets, and struggling to let them go. I enjoyed it a lot.

What I have wanted most is many lives. One for each longing, round and separate.

Day 31: In Conclusion, Gratitude

There is no way I could pick a favorite among all of these incredible books. But Be Holding did something to my brain and heart that doesn’t happen very often—a remaking, rewiring, reseeing. I’m not ready to reread it yet, but in honor of how profoundly moved I’ve been by Ross Gay’s work recently, I’m going to reread his gorgeous collection Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude for the last day of the challenge tomorrow. This month of poetry has been an endless and ongoing catalog of unabashed gratitude.

Laura, what a feat! This was -- is -- so inspiring. I'm definitely doing it next year (though, probably with children's poetry 😉) Kudos on this incredible roundup of your month!